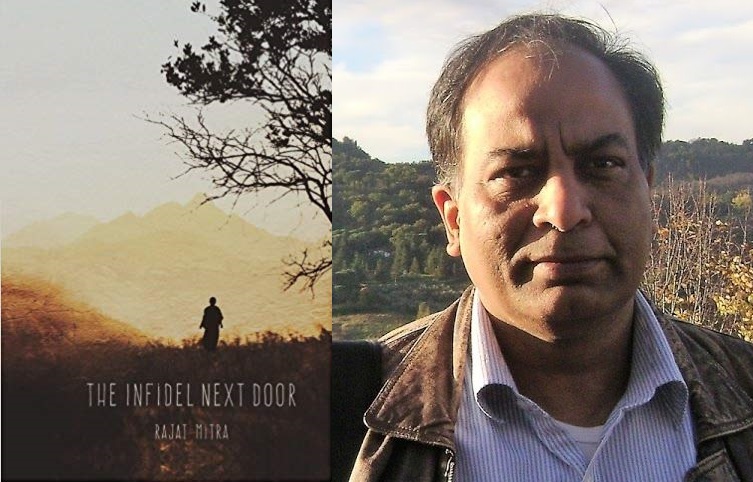

Book Review: The Infidel Next Door By Rajat Mitra

“When a man fights for truth, he is the loneliest,” says a character in this novel The Infidel Next Door. This is the idealistic message which the author Rajat Mitra wants to convey. He is right because not many writers these days have the courage to swim against the tide of prevailing intellectual discourse and call a spade a spade the way he has done.

A page-turner coming from a psychologist may not be something new, but this debut novel from Rajat Mitra certainly has a different approach to the conflict in Kashmir. That is because the writer has worked for many years at the ground level with both the victims and the perpetrators of ethnic violence. Despite the author being from a domain different from literature, this novel has all the adornments of a literary piece – individualized characters, realistic situations and a plot full of suspense.

Of late, interest in Kashmir has risen and quite a few writers like Urmila Deshpande, Abhay Narayan Sapru, Anita Krishnan, Feroz Rather and Humra Quraishi have published novels based on life in Kashmir. Not long ago, Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness appeared, which, contrary to the title, presented a cynical view of things. Mitra’s novel ends on an optimistic note, with engaging perspectives on historiography, politics, religion, etc.

The story of the novel is set in the 1990s, when the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits started as a result of rise in terrorism. But that was not the first-time exodus. Long ago, Aurganzeb’s forces let loose a reign of terror on Kashmiri pandits because the tenth Sikh Guru Teg Bahadur refused to convert to Islam. He had been requested by the pandit community to save them. Thereupon, he threw a gauntlet to the king to first convert him, if he could. Aditya Narayan lost his ancestor in that carnage and since then his forefathers had been living in Banaras. While the history of Aurangzeb’s rule is well known, the memory of Battmazar, an island in Dal lake is not so well known to the outside world. It is where hundreds of Hindus had been buried alive during the cruel Pathan era in Kashmir, leading to another exodus of Kashmiri pandits from the valley.

Aditya’s guru, referred to as Gurudev in the novel, demands as gurudakshina the re-building of the Adi Shankar temple near Srinagar, because “If this temple survives, Hinduism will survive in Kashmir.” Aditya goes along with his parents to Srinagar and starts the construction of the temple which is in ruins. In doing so, he faces stiff opposition from the hotheads among Muslim community because a mosque stood alongside the ruins of the temple.

The Imam of the mosque is a liberal Muslim. He has adopted the orphan girl Zeba and brought her up along with his son Anwar who, however, becomes a stone-pelter under the influence of Haji chacha, the villain of the piece. Aditya, through his Gandhian ideals and spiritual mindset wins Zeba’s heart and is able to generate humane feelings in Anwar who saves the life of Aditya. Later, Anwar becomes a conscientious person, who tormented by the memory of his past action, tries to find answers to ethical questions. Finally, Aditya renounces the world. The story ends with Aditya’s permission to Anwar to write on the ruins that the destroyed temple is a symbol of intolerance and his wait for Aditya is a symbol of hope.

Aditya Narayan comes out as a deeply spiritual person and has no interest besides performing the rituals at the temple and keeping it in order. He may appear to be too virtuous to be true but then the intent of the novelist seems to be to yearn for such a character who can only build bridges between the two communities.

The novelist has experience of life in Kashmir, so he is able to find out the root cause of the misconceptions which the Muslims have about Hindu religion and way of worship. The education of Muslim children in madarsas is partly responsible for a narrow view of religion. The public discourse outside school is controlled by fanatics like Haji chacha for whom azadi (freedom) means “when our land will be free of infidels.” There are slogans written on the walls of houses of Hindus asking them to leave or face the consequences.

The terrorists, who get funds from abroad, issue diktats asking women to remain in purdah or face acid attacks. They are against the use of cosmetics and fancy dresses for them, though they won’t mind such stuff for their mistresses even as they are cruel at heart. Zeba is married to Salim, a terrorist to avoid the stigma of being in love with a Hindu, but Salim murders her to prove his dedication to the cause of “azadi”!

To be fair to the writer, the writer does not shield Hinduism on the issue of casteism. While Aditya and his mother are all for treating the two dom caste characters as equal, his father is not able to reconcile to it. If Aditya is the icon of liberal Hinduism, Anwar becomes a liberal Muslim following interface with Aditya. As a practising psychologist having worked with cases of trauma and violence, Mitra is able to depict convincingly the change in Anwar who is perplexed at the thought of having saved Aditya whom he initially wanted to kill. To this, Javed, his friend and the other pacifist who is converted through Anwar’s example, explains: “You hear the voice of God in your ears, when you save your enemy from dying.” Thus, love triumphs over conscientious people.

Also Prof. Baig, the Vice Chancellor of Jammu University is a brave and upright Kashmiri intellectual who places the composite culture of Kashmir above religion. He is the one who enthuses Aditya when he is depressed. In a hard-hitting article, Prof. Baig asks the militants what right they have to claim victimhood when they perpetrate collective violence upon pandits.

While the army’s role gets kudos from the writer, that of the police force is not commended as some of its personnel are seen hobnobbing with terrorists which leads to the alienation of the Kashmiri youth. Mitra also blames Article 370 for the present state of Kashmir.

The novel is written in lucid language. It is replete with quite a few quote-worthy lines like “History is like an empress, angry with a whip in hand, who demands obedience to the written word. Memory is the mother who holds us in embrace, protecting us when our soul needs answers.” Mitra has carefully given in footnotes the meanings of Kashmiri and Hindi words for the benefit of readers. All these are also compiled in the form of a Glossary at the end. The 355-page novel is divided into 100 short chapters, but it goes to the credit of the author – he should know it being an experienced psychologist – that he keeps the interest of the reader alive creating suspense wherever the story seems to sag.

Featured Image: Amazon, Pinterest