Meaning of India in Words of Raja Rao: Brief Life Sketch of a Novelist as Sadhaka

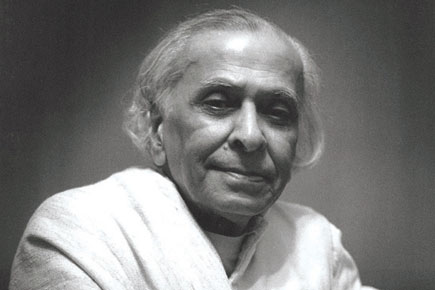

On the occasion of 108th anniversary of Raja Rao, one of India’s most illustrious English language writer, IndiaFacts presents “Meaning of India” in his words, written by his wife Susan Raja Rao.

Raja Rao was born on November 8, 1908, into an old Brahmana family whose spiritual lineage dates back to the 13th century. The family home was built next to a temple and Dharmashala, both built by distant relatives. A life-time wanderer, Raja loved to tell the story of being born in room number one of his family’s pilgrim inn.

His grandfather, Ramakrishna’s presence was the greatest influence over his early life. The family patriarch did nothing, but meditate from early morning until noon. After lunch, he would read or teach Vedanta to anyone, who wished to listen. Raja’s father, HV Krishnaswami, influenced by the modernism of the time, studied Anglo Saxon, taught English and thought the English language was sacred. Raja had to learn Sanskrit against his wishes, but this opposition intensified his search for Indian values. Emerging from the classical Indian background of his grandfather, Raja began his philosophical, spiritual quest. Though, he would study many world religions, philosophies and cultures, he always knew Advaita Vedanta was the ultimate path.

The following are the words of Raja Rao on Vedanta:

“There is no India without the Vedas – as there’s no India without the Ganges or the Himalayas.

And what’s the secret of the Vedas: it’s Vedanta, the end of the Vedas, or if you will, the end of knowledge (for Veda comes from the root vid: to know). So, it would be truer to say, there’s no India without Vedanta [1].”

“What is man’s estate? Is it to love the rivers and the forests, to glorify the world and the spenders of his making, or is it to know, to realize the estate of his state? Where is he from and where does he go? Koham Kutham? asked Sri Sankara. And what is it that I see? Unless I know whence I came, would I know what I am? And if I know what I am, would I see the world as I saw it before I knew the background, the background of my instruments of perception? Ultimately, what is it I see, comes back to who sees. If you can decide this, we have resolved, according to India, every problem of philosophy [2].”

“Being excludes nothing, becoming choses, for evolution predicates choice. In daring the Truth, India became fearless again. In knowing it she saw herself. The Vedas became contemporary and Vedanta actual. The great sage showed the rose as rose and India became ‘free’ not politically, but metaphysically. Thus going back, as it were, to the source of the Ganges, she discovered the nature of water. ‘Water is not stagnant water. Water is not flowing water. Water is just water [3].”

Raja, while earnestly seeking his spiritual path, appalled by the terrible corruption of the Brahmanas in Banaras, threw his initiation thread into the Ganges. Still desperate to find his answers, at nineteen years of age, he left for France, attending the University of Montpellier to study literature. He always said that it took him one week to discover that he could find the Truth he was seeking only in India. He began returning to India, staying at the ashram of Pandit Taranath. While Raja found him deeply impressive, he was not the Sat Guru, he was searching for.

Just before the war, Raja realized he could go no further in his spiritual quest, on his own. Having found success and recognition writing his early short stories and first novel, Kanthapura, he returned to India, taking a sacred vow not to write again until he found his Guru. His search lead him to the very great sage, Ramana Maharishi, then Sri Aurobindo, and finally to Mahatma Gandhi. Though he was deeply moved by and admired each great man, he knew he had yet not found his own Guru.

Raja returned to the ashram of Ramana Maharishi. There he wept day after day in despair that he might never find his Guru. A compassionate Englishman, David Maciver, told him that he knew where he could find what he was seeking. Raja would always tell the story with a mischievous grin, of how it was not an Indian, but an Englishman who had taken him to his Guru. They went to Trivandrum to the great Sat Guru, Sri Atmananda, the greatest, according to Raja, since Sri Sankara in the 8th century.

Again, in the words of Raja Rao on the Guru:

“Thus, I had connected myself with the great Indian tradition, started as it were with the Vedas, from an unknown age [4].”

“At the apex of Indian civilization is the Guru. There was always the Guru. Everything in Indian civilization, whether it is for music or metaphysics, grammar, or yoga, or archery, you always go to a Guru. When you have gone from one Guru to another, having received all that each one could give, and then knowing what is to be known, you hear of another, and say, this is it perhaps.

The search for the Guru is the search for home. You realize that even in the smallest little atom, which you probably were in the beginning of creation, you have only sought Him and Him alone.

So you go on, according to the Indian tradition, life after life, only to seek that from which there is no returning. You go on gathering wisdom from Guru to Guru till you come to the Guru (the Karana Guru) and then you say, ‘Now I have come, I have come to the haven, the home. I have come to Him.’ And when you reach His Feet, and you say, ‘Of course, there He is, I have always known Him.’ The search has ended and now there is nowhere to go, for there is no where, there is no movement, and there is no me, and the ‘I’ could go nowhere. You are where you have always been: at His Feet [5].”

Home at last, Raja stayed at the ashram of Sri Atmanada for some time. He had still not returned to his writing. One day, the Great Guru passed by him and said, “Raja, what are you doing?” Raja prayerfully replied, “Nothing at all.” Sri Atmananda gently instructed, “I think you should begin writing again.” From this moment forth, Raja’s whole literary genius turned to the spiritual. Throughout his life, his writing became more and more exalted as he grew in discipleship. Raja had never written for money, fame or any audience. He now said that what was good about his books belonged to his Guru and the mistakes were his. Raja knew the Word was sacred and for him, writing was worship.

The following are the words of Raja Rao on the Indian concept of writing and the Word:

“The word is indeed eternal. Man faces himself, when he seeks the word. The word as pure sound is but a communication that comes from silence. The word is but vibrant silence compounded into a momentary act. The act has to be like prayer, if it should yield what you want it to yield. Even to say a flower, let alone Rama, you must be able to say it in such a way that the force of the vocable, has the potency to create the flower. Unless the word becomes mantra, no writer is a writer, and no reader is a reader [6].”

“What then the origin of the word, of Sabda, of sound. Since before speech there was no sound, and after the sounding of the word, there is no sound or word, the background of sound or Sabda is silence. Not a lack of sound, but rather the womb of sound, from which arising, the sound goes back to its own reality. The self of the sound, then, is again silence. And silence is Brahman, the Absolute, the Uncreate. Creation is the seeming daughter of silence going back to the Mountain Lord. The feminine principle returns to the masculine, when both are dissolved into their essential nature.

But why should silence become sound? It’s because of lila, the playfulness of nature. Love-making is play. Thus, silence playing with its expression, is sound. And the enjoyment of this love-making is rasa, the aesthetic joy of the unmanifest rising to manifestation, only to go back to its own background, thus the circle is complete, and nothing ever happens, just as waves go back to the sea, reaching back to its source, which is water. When sea and wave realize that they are both water, is the moment of true enlightenment.

Liberation then, is serious play. The writer plays with himself, as word, with words [7].”

The sacred wordsmith passed away in perfect peace, on July 8, 2006, just four months before his 98th birthday. During his life, Raja shared the wisdom of India with thousands of people around the world, as a teacher and author. He had lived his life and faced his own spiritual journey with unshakable courage, boundless enthusiasm and generosity, and a loving, joyous heart.

By the grace of his Guru, Sri Atmanada, Raja, having completed his literary and teaching Sadhana, became Pure Experience.Finally, in the words of Raja Rao:

“All this shows to you that wisdom does not belong to any one nation, as sometimes we Indians in ignorance seem to boast of, as if we had the monopoly of it – but that wisdom is without kaladesa, without time or space, and to me, India is anywhere there is neither time nor space. Much as I love the Ganges, and the Himalayas, where I shall be going tomorrow, that snowy home of our Sages, the founding fathers, so to say of this land, yet must we never forget, the Truth belongs to no-one, and he who has even a small inkling of it must realize that it shines in every human heart – indeed, it shines wheresoever we look, for Truth is itself light, the light in any perception. So you could say ladies and gentlemen, if you will, India is perception or in the triputi of seer, seeing, and seen, seeing alone is India. In that sense, every human being is an Indian [8].”

References:

- Saints and the Sage, page 7, unpublished transcript of Raja Rao’s lecture series, The University of Texas at Austin,1963

- Saints and the Sage, page 145

- Saints and the Sage, pages 1 and 2

- Letters, Raja Rao and Kathleen Raine, page 51, letter written to Kathleen Raine November 7, 1972

- Saints and the Sage, page142

- The Meaning of India, page155, essay, “The Writer and the Word.”

- The Eye of the Beholder, edited by Maggie Butcher, page 45, essay, “The Cave and the Conch: Notes on the Indian Conception of the Word.”

- Daughter of the Mountain, unpublished second volume of The Chessmaster and His Moves trilogy, pages 360-361