Decolonize Minds, Revive Dharma: A British Scientist’s Call to Hindus Worldwide

Image Courtesy: Hindu Dvesha

In an era where ancient wisdom often clashes with modern narratives, few voices resonate as powerfully as that of Dr. Melissa Kapoor. An Oxford-trained scientist, British Hindu convert, and passionate advocate, known affectionately as “English Bahen,” she continues to actively champion pro-Hindu causes. With a vibrant presence on X (@English_bahen), where she addresses issues like the persecution of Hindus in Bangladesh, and through her insightful YouTube content on channels such as The Festival of Bharat and Citti Media, Dr. Kapoor defends Hinduism, raises awareness about historical and ongoing challenges faced by Hindus, and celebrates the eternal beauty of Sanatana Dharma.

In this online conversation with Pradeep Krishnan, Dr. Kapoor shares her remarkable journey from a high-achieving British academic to a devoted Hindu, offering profound insights into spirituality, culture, and the future of Bharat.

Please tell us about yourself—your place of birth, parents, education, and early life.

I was born in the late 1980s on the outskirts of London, the daughter of a second-generation Polish immigrant who worked his way to a university degree, and a Danish air hostess. My childhood in rural England was defined by a steady climb toward success: a happy home life, academic excellence, and my first national sporting title.

At eleven, I entered a prestigious girls’ Grammar school where the culture was one of relentless ambition. We were conditioned to be the “movers and shakers,” urged to break glass ceilings in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics). Influenced by this, I traded my childhood dreams of archaeology and my talent for art for the rigor of science and math. By my late teens, I was a four-time national sports champion with some of the highest school grades in the country, convinced that life was simply a collection of titles and certificates.

This momentum carried me through a BSc in Physics at Imperial College and a DPhil in Statistics applied to medical imaging at Oxford, adding four more national titles along the way. But by the time I finished my doctorate, the cost of “having it all” became clear. I was 26, mentally burnt out and physically collapsing. Most of my peers from that same high-pressure environment were facing similar crises. Our mentors had promised us the future, but they hadn’t warned us that it might cost us our health while still in our twenties.

Transitioning into medical technology consultancy, I found work I enjoyed, yet I spent every day battling a storm of neurological symptoms, including pain, dizziness, tremors, and severe brain fog. For the first time, the path wasn’t clear. After a lifetime of winning, I found myself in a bleak struggle just to survive the day.

How did you meet your husband?

Amongst the bleakness of my illness, there was a ray of sunshine. I met Akshay, an Indian who had moved to the UK to study about ten years previously. He was a more effective medicine for my symptoms than any pharmaceutical, teaching me that it is not just okay but good to take time out to relax, that I should prioritize my health over working harder and harder to win awards, and that there is a whole world of fascinating history, religion, philosophy, and politics to learn about.

We got engaged, and I visited India for the first time. It is difficult to put into words just how magical that first visit was. The colorful buildings, clothes, and food, the energetic singing and dancing, the hustle and bustle of the markets, and the beauty of being part of Puja at Diwali helped me feel, for the first time in almost three years, that life was worth living again.

Three months later, we had a traditional Hindu wedding in India, giving me the opportunity to meet many of my husband’s wider family for the first time. My in-laws arranged for the meaning and symbolism of every step, ritual, and mantra conducted by the Pandit ji and our families to be explained in detail in English for my benefit. Our beautiful Hindu wedding helped me see firsthand how full of wisdom, deeply sensitive, and meaningful Hindu traditions are. It left me eager to learn more.

What drew you towards Hinduism, and what was the pivotal turning point in your life that led to this attraction?

Having experienced a new breath of life through meeting my husband, visiting India, and receiving a beautiful Vivah Sanskar (sacred Hindu wedding ritual), my attraction towards Hinduism continued to grow. This growth was so organic that there was no single time point when I made a conscious decision to become a Hindu or when I realized that I was a Hindu. But some clear events and experiences stimulated and nurtured this transition.

An early experience was discovering and listening to online discourses about Advaita Vedanta at bedtime. I felt an effortless resonance with the concepts of non-duality. Any worry or other negative emotion that I was still carrying with me from the working day would disappear, and I would feel like I was melting away. After some time, I found the wisdom of Vedanta was radically altering my perception of existence, giving me a new level of mental strength, courage, and confidence that was allowing me to cope better with my illness, to manage my professional activities more effectively, and to be more at peace in my personal life.

Another experience that nurtured my transition to Hinduism was how I felt it empowered me as a woman. In the West, the notion of equality of the genders at times is misplaced—there should, of course, be equality of opportunity, equality of reward, etc., but where I feel gender equality has gone too far is where it leads to women feeling they need to reject or erase their femininity. Seeing Hindus celebrating Ma Shakti in all her various glorious forms and receiving so much love and wishes from my Hindu family because I am the Laxmi of the house has really made me embrace my femininity and feel stronger and more complete.

What inspired you to choose marriage in the traditional Indian way with Vedic rituals, and why do you consider these rituals important in one’s life?

Hinduism did not feature on the education syllabus while I was at school, and so I knew absolutely nothing about Hinduism before meeting my husband. By the time of our Vivah Sanskar, my understanding had grown, though I was still only scratching the surface of its vastness.

Having fallen in love with the color, energy, and life of India during my first visit, I knew I wanted to get married there. Suddenly, the idea of getting married in a grey church with everyone sitting silently in straight rows was not appealing at all. I also knew that a secular registry office would not offer the spiritual depth I now craved.

I owe the beauty of our Vedic ceremony entirely to my in-laws. They recognized my husband’s deep desire for a truly Hindu union, and looking back, I am profoundly grateful too. It wasn’t just a ceremony; it was an entry into a world of meaning I hadn’t known was missing.

What, in your view, is unique about Hinduism, and how does it differ from other religions, particularly Christianity and Islam?

The main difference between Hinduism and the Abrahamic religions is that Hinduism realizes all is Brahman—that all of existence, in all of its most complex forms, and throughout all of time, is interconnected and divine. This realization creates a harmonious, empowered, and sustainable existence between lifeforms and across millennia. When a human realizes they are at one with animals, plants, and Earth’s materials, that their actions and thoughts have consequences (the karmas of which they each must undo over many lifetimes), and that they are empowered to make decisions for themselves within an overarching framework of eternal righteousness, they are much less likely to cause suffering, destruction and devastation. They are also more likely to be at peace internally, because they are cognizant that their true self is not their ego, but Brahman.

Compare this to the Abrahamic religions that propose God is a male figure looking upon his chosen race (humans) and casting those who do not believe in Him in the “right” way, or who do not follow His simplistic commandments, into eternal hell. Naturally, this leads believers to develop inflated egos because they believe it is their duty to “save” people who believe differently. It also creates conflicts for believers who try to reconcile simplistic, dated dogmas with the complexities and advancements of modern life.

That is how I see the major difference between Hinduism and other religions play out from a practical perspective. But, for me personally, the main difference is that Hinduism is Truth and the others are not. Hinduism is logical, comprehensive, and has not been disproven by modern-day science (unlike other religions, which say the Earth is only 6,000 years old, etc.). Hinduism is a science far beyond what is perceived as science today. And, unlike religious dogmas, science never needed to be founded because it just is.

These differences show very clearly that all religions are definitely not all the same or equal. Only different Hindu ways to moksha are equal. This can be explained metaphorically with the idea of climbing a very high mountain, at the top of which resides the Supreme goal. The Hindu Mountain is completely separate and different from the mountains that Christians and Muslims try to climb. It is also orders of magnitude higher. There are different paths up the Hindu mountain, like bhakti, yoga, Vedanta, but climbing the Christian and Muslim mountains instead of taking a path up the Hindu mountain will not take you to the truth, the supreme goal.

What led you to move away from Christianity and embrace a Hindu way of life?

Once I came to appreciate the vast knowledge and wisdom of Hindu Dharma, the antiquity of its history, and the benefits it has for worldly existence, it was simple to see that it is closer to the Truth than any other philosophy, ideology, or dogma that exists in the world. I sometimes wonder whether the transition was made particularly simple for me because:

- I am a scientist, and so the irrefutable evidence of vast, supreme knowledge contained within the Hindu scriptures is very persuasive to me (and the limitations of simple dogmas are very dissuasive to me).

- I feel I have always had sensitivity to hidden depths of existence, particularly exposed by music, art, dance, etc., which have always impacted me on a profound level.

- It has always been straightforward for me to feel detached from my body. In fact, I remember as a child that I would quite often have “out of body” type experiences that left me questioning the reality of the material world. Hearing about Vedanta as an adult helped me have these experiences once again.

I feel many Westerners would become Hindus if they could come to learn about it and were able to make rational, externally uninfluenced decisions about it. One thing that Hindus can do to help Westerners realize the beauty of Hinduism is to be proud, strong Hindus. People are naturally attracted to that which appears strong, powerful, and confident. When Hindus are apologetic for being Hindu, outsiders will naturally see them as weak and Hinduism as something to poke fun at.

There has never been a better time for Hinduism to shine, as there is rising awareness in the West of the devastation caused by the Abrahamic faiths, the need to be respectful of nature, and the damage that materialism and ego are having on mental health. Hindus have a responsibility to help the world see that the solution to a sustainable, healthy, and happy future is for the world to embrace Hindu Dharma.

How do you conceive of God?

Brahman is everything. The creator, material, and single consciousness of the universe (and, most probably, multiverses). An intelligence of infinite force, qualities, and possibilities. Visible matter, anti-matter, dark matter, and the sum of all energy and forces, including dark energy, consciousness, and divinity.

While the abstract nature of Brahman and Advaita Vedanta can be difficult for the human mind to fathom, Hinduism compassionately caters to our limitations by manifesting Brahman in forms we can relate to. For a devotee living in Kali Yuga like myself, possessing limited knowledge and potential, the path of Bhakti to a sagun (manifest) form is not just a choice, but a necessity.

By focusing on specific manifestations like Bhagwan Vishnu, Shiva, or Ma Durga, we can grasp individual facets of Brahman. Whether it is the sweetness of Bhagwan Krishna or the unwavering determination of my Ishta Dev, Hanuman Ji, these forms allow us to aspire toward the divine qualities of Brahman. Where my intellectual understanding falls short, I strive to fill the void with total surrender.

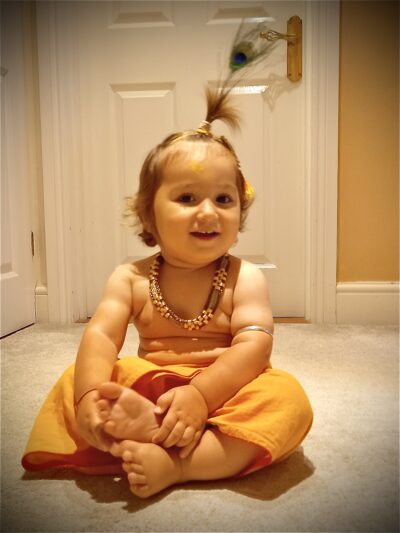

(Dr. Melissa Kapoor as a baby)

How do you view Bharat as a unique country shaped by diverse religions, castes, creeds, communities, and ways of life, and what, in your opinion, lies ahead for India/Bharat?

Bharat is the land of the Hindus and the Hindu religion. It represents the world’s oldest and grandest religion and civilization, a sacred geography defined by wisdom rather than mere borders. Its roots reach back at least 15,000 years, yet its scientific contributions feel incredibly modern. Long before the European Renaissance, the Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics was pioneering calculus and infinite series. From architectural marvels that defy modern engineering logic to a medical and surgical tradition that remains remarkably relevant, Hindu science was not just ahead of its time; it set a standard for human inquiry that we are still rediscovering today.

This brilliance was the heartbeat of a singular civilization stretching from Afghanistan to Myanmar. While the outward expressions, like dance, language, and cuisine, vary like the diverse colors of roses on a single bush, the essential roots remain identical across the landscape of Bharat.

Bharat stands as a rare survivor of antiquity, having outlasted foreign powers intent on erasing its Hindu Dharmic identity. The expansion of Abrahamic dogmas brought an ideology of total erasure that dismantled civilizations across the globe. Bharat, however, stood its ground through centuries of physical resistance against relentless invasions. Yet, the British colonial era proved perhaps more insidious, shifting the battlefield from the land to the psyche.

The “Macaulayism” of the education system was a deliberate attempt to colonize the Hindu mind, knowing that Bharat could only be ruled if its people were alienated from their own brilliance. Knowledge was suppressed, history was rewritten, and social structures were weaponized. A prime example is “caste”: a term derived from the Portuguese “casta”. This external label distorted the indigenous social fabric by changing the fluid, meritocratic concept of Varna into a rigid, birth-based hierarchy.

The future of Bharat hinges on its ability to discard its mental colonization and return to its Hindu roots. Bharat must embrace Hinduism directly and openly as its core and fundamental identity. The solutions to our modern challenges lie in Hindu wisdom. A critical step in this reclamation will be moving away from the linguistic hegemony of English toward indigenous languages. If Bharat can achieve this and reintegrate those separated from their ancestral Hindu religious roots, it can become the most prosperous and harmonious nation on Earth within our lifetimes.

You participated in a march in London in support of the CAA. What are your reasons for supporting the Citizenship Amendment Act passed by the Indian Parliament?

When parts of India were carved out to create a Muslim country in 1947, the Indian leaders promised all Hindus and Sikhs who had not been able to get to India that they could come to India anytime if they felt unsafe in Pakistan. Nehru and the Pakistani Prime Minister signed a pact in 1950 to ensure safety for the respective minorities of both countries. India lived up to its promise, and the population of Muslims grew from 8% to 14%, but Pakistan (and later Bangladesh) persecuted religious minorities, and their population reduced from 23% to 3%.

The people benefitting from CAA have horrific stories to tell from when they lived under the Islamic state: they have been threatened, their daughters have been abducted and converted, their homes and businesses have been burned down, and their brothers have been murdered.

That is why these minorities are desperate to get out of the Islamic states of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. And then, when these poor people came to the safety of India, what did they get? The indignity of not having the right to education, healthcare, employment, and vote. They could not even get gas connections to cook their food. Some have lived without these rights for 70 years.

While Hindu philosophy is gaining wider acceptance across the world, in India, the teaching and study of Hindu philosophy and its sacred texts are often labeled as anti-secular. How do you respond to this perception?

The perception in India that teaching and studying Hindu philosophy and its sacred texts is anti-secular is a consequence of the psychological colonization pursued by the British as part of their well-planned strategy to rule India. Macaulay started this in the mid-1800s, and his successors carried it out. The main plank was making English the medium of instruction. The results are available for all to see today.

I feel Indians simply do not realize the damage the English language has done to them. No country in the world has adopted a foreign language and prospered. Look at Germany, Japan, Russia, France, etc. All were devastated by World War II, but all rebuilt and achieved great heights, and all did it in their own cultural context and language.

English comes from a Judeo-Christian philosophical framework, and by speaking in it, your whole worldview subtly changes. Academic linguists from the USA conducted a study in UP and proved this. This subtle shift in worldview reinforces mental colonization and everything else flows from that: the rejection of the Hindu religion, misinterpretation of shaastras, flawed legal system, etc. Secularism is also a Western concept that originally came up to protest against the Church. It is simply not relevant in a Sanatan context.

While Hindu philosophy, culture, and ways of life are gaining increasing acceptance in the West, many Indians appear to be preoccupied with imitating Western models.

There is a burgeoning realization in the West that rampant materialism is devastating the human psyche and the planet alike. Consequently, we are seeing a greater alignment between progressive Western ethics and ancient Hindu philosophy than has ever occurred before. Unfortunately, this synergy remains largely unrecognized by both sides.

Ironically, as the West begins to question the sustainability of its own models, many in Bharat are doubling down on these outdated frameworks, self-inflicting “Colonialism 2.0” with consumerism at its core. By aspiring to a Western ideal that the West itself is beginning to reject, these individuals become complicit in their own cultural displacement.

From a psychological standpoint, consumerism is a failed hypothesis. Research consistently shows that it heightens the risk of chronic disappointment, anxiety, and isolation. No matter how much material wealth or social status is accumulated, it can never satiate the fundamental human needs for security and genuine connection. These are extrinsic goals, and they are inherently fragile.

In contrast, Sanatana Dharma has always prioritized intrinsic goals: self-knowledge, personal growth, and the cultivation of deep, meaningful relationships. These are the primary protectors of human well-being. The West is currently in desperate need of this wisdom, yet many Hindus are discarding it at their own peril. To trade a time-tested philosophy of internal fulfilment for a superficial culture of consumption is not progress—it is a civilizational regression.

What are your views on religious conversions and proselytization? In Europe, including the UK, there has been a noticeable trend of conversions to Islam—how do you perceive and interpret this phenomenon?

The nature of a conversion is defined entirely by its “why.” A transition born of genuine intellectual inquiry and a free-will alignment with truth is part of the human spiritual journey. However, when conversion is achieved through emotional manipulation, material incentives, or social pressure, it ceases to be a spiritual act and becomes something far more sinister: a tool of expansionist geopolitics.

For a Hindu, conversion is particularly tragic because Sanatana Dharma is not a set of dogmas to be “believed”; it is an ecosystem of knowledge fine-tuned over millennia to the geography, biology, and psychology of Bharat. When a Hindu converts, they are essentially divorced from this practical wisdom: the Ayurvedic health practices, the seasonal rhythms, and the environmental ethics that allow a human to live in harmony with that land. Beyond the physical, they lose the precise spiritual maps designed to lead them toward Moksha. They trade a bespoke path to liberation for a foreign dogma.

Regarding the trend of conversions to Islam in Europe and the UK, we must look at the psychological appeal. One cannot ignore that many modern Muslims possess a profound, unshakeable confidence in their identity. In a Western world currently drifting through a vacuum of meaning and moral relativism, that level of certainty is highly attractive, especially to the youth. People are naturally drawn to strength and conviction.

There is a vital lesson here for Hindus. Through my travels in India, my interactions with Indian friends and family, and my observations of the Indian media, I identified a profound “crisis of confidence” within the Bharatiya psyche that makes the community vulnerable. They are terrified of the word “Hindu”. If Hindus were as unapologetically confident in the superiority of their own religion as others are in theirs, the appeal of foreign dogmas would vanish. Confidence is the greatest shield against proselytization. Hindus must move past the habit of apologizing for their religion and traditions and start embodying the fierce, intellectual certainty that a 15,000-year-old civilization and Sanatana Dharma deserve.

What are the various activities you have undertaken in support of Bharat and its culture?

The crisis of confidence of Hindus is the predictable outcome of a thousand years of systemic trauma. From the physical destruction of ancient universities and libraries by Islamic invaders to the psychological “Macaulayism” of the British Raj, the goal was the same: the erasure of Hindu identity.

The tragedy of modern India is that the British education system remains dominant nearly 80 years after independence. This has created a class of Indians who suffer from a colonized mindset. In its most extreme form, this manifests as self-hatred, where individuals perpetuate the very lies that were used to oppress their ancestors. I felt a moral and intellectual duty to intervene, to defend the truth and counter the injustices faced by over a billion people. Drawing on the strength and clarity I found in Sanatana Dharma, I began creating content under the pen name “English Bahen ke Dil se” aiming to dismantle colonial misinterpretations and illuminate the sophisticated, scientific, and beautiful nature of the Hindu civilization.

However, my most vital contribution is closer to home. I am raising my young son to be a strong Hindu anchored in his heritage. We spend about an hour every day practicing bhajans and shlokas, and I always try to direct our conversations toward Bhagwan and helping him to understand Dharma. He is not just my son, he is my greatest legacy, and so my most important duty is to ensure he develops a mind free from colonization and a heart full of devotion for Bhagwan.

What steps, in your view, can be taken to build a strong, united, and culturally vibrant Bharat?

To build a strong and vibrant Bharat, the nation must first accept that Hinduism is a religion and India is the land of the Hindus. This process of decolonization is not merely political; it is deeply personal and cultural.

- Linguistic Sovereignty: True decolonization begins with the reclamation of indigenous languages. Language is not a neutral tool; English was forged by a specific worldview, rooted in Western geography, Christian theology, and European attitudes. When English becomes the primary medium for informal, daily life, it subtly reshapes the cognitive frameworks of the speaker, alienating them from their own cultural nuances. Prioritizing native languages is the first step in realigning the Hindu mind with its own roots.

- Educational Reformation and Parental Duty: The current education system, a relic of the colonial era, must be overhauled to reflect the true history of Bharat. Although political and administrative reform is essential, parents must also take matters into their own hands. As Hindu parents, we must become scholars of our own itihaas and shaastras. By arming ourselves with a clear understanding of and devotion to Sanatana Dharma, we can answer the inquisitive minds of the next generation, ensuring they are nurtured with values they will never wish to abandon.

- Diversifying Intellectual Influence: For too long, the Bharatiya “success story” has been limited to medicine and engineering. While these are noble pursuits, we have surrendered the narrative-shaping fields. We must encourage our Dharmic children to become historians, archaeologists, journalists, and philosophers, too. By mastering the humanities through a Dharmic lens, they can dismantle the biased narratives that have marginalized Hinduism. And for that, they must be encouraged to be practicing Hindus.

- Equal Rights for Hindus: It is deeply unjust that Hindus do not enjoy constitutional parity in their own land. Bharat must end government control over Hindu temples and restore their administration to independent Hindu religious institutions, just as mosques and churches are governed by their respective communities. Hindus must be given the same rights to have Hindu schools as other religions do. Hindus must be allowed to celebrate their festivals like Diwali with crackers, wear a tilak and kalawa (sacred red and yellow thread used in Hindu rituals) without having to take them off in exam halls, etc. There are thousands of examples of state discrimination against Hindus that I have seen over the years. This must end.

- Gauraksha: Bharat must unapologetically uphold foundational Dharmic principles like Gau Raksha, which is a civilizational and religious imperative deeply woven into Hindu ethics and spiritual consciousness. Because Gau Mata has been revered across millennia, her protection should be upheld as a fundamental national moral responsibility. To reflect this, all gauvansh (the Indian lineage of cows, bulls, and calves) must be protected through uniform and strictly enforced laws—a mandate already in the Directive Principles of State Policy of the Constitution.

What message would you like to convey to the readers?

As someone who was not born into Hinduism but found my home within it, I see its value with total clarity. Hindu Dharma is the light the world needs, yet that light is being dimmed by those who do not understand its worth. Between the external pressure of conversions and the internal disdain for Hinduism, the fabric of Bharat is being stretched thin. My message is simple: wake up to the greatness of your own religion. Reclaim your religion, language, teach your children the shaastras and true itihaas, and stand firm in your religious convictions. The future of the planet may well depend on the resilience of the Hindu mind.