A Critique of Amanda Lucia’s “Guru Sex”

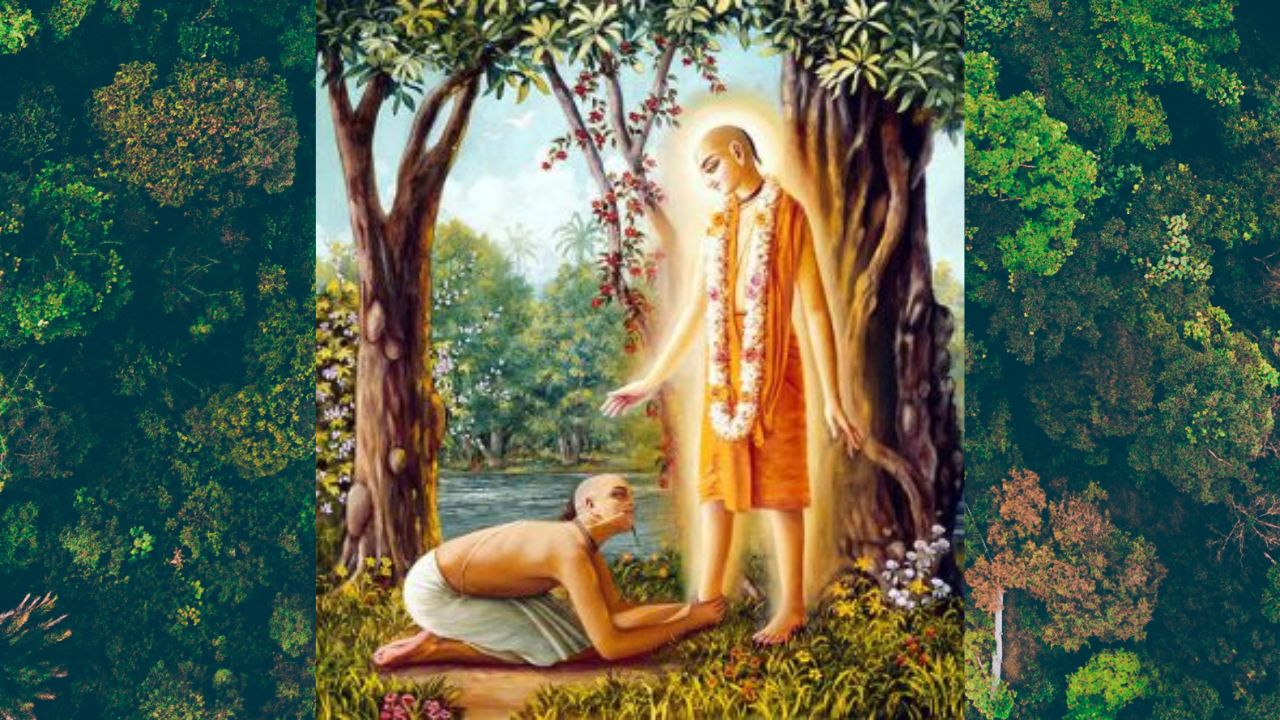

Image courtesy: Vedanta-Red Zimbala

As an embittered student who never got a scholarship to study in Britain, my academic fulminations against Western scholars of Hindu gurus have been private ruminations as I sought to bridge the chasm between “objective” religious interpretations and “subjective” accounts of experience that have hitherto dominated the field of new guru movements and their devotional communities. Studies of organizations run by self-realized masters have focused on sociological analyses or hagiographic glorifications with nothing to bridge the gap. This lacuna in Western academe’s dogmatic approach to “objectify” the “other,” and the conservative devotional outpourings of devotees, both of which have their failings, never seem to meet to converse, although my attempt here was to, and was received by left-liberal scholars who gave me a space to articulate my opinions sans much editing. Good for the Brits!

But let me do a little rummaging through my past to grasp Western-style academic thought more clearly. My experiences as an undergrad at Christ University in Bengaluru many moons ago touch a point I seek to explore. During my final year there, a professor named Anil Pinto (now the Registrar at Christ University) asked me to write an essay on Tejaswini Niranjana’s heavy-duty book on translation. I could not make sense of it as it was full of jargon, but I ended up critiquing the book by using Rajiv Malhotra’s analytical tools in Being Different—which was an important book in the Indian right-wing ecosystem at the time. During the late noughties, Christ University was a bastion of leftist propaganda and its humanities and social sciences department was an eerie zone of Catholic traditionalism, which made it a place for academics like Anil Pinto to use the vocab of cultural studies in Christian garb, and juxtaposed by the meanings which were ascribed to oft-repeated Marxian epithets against power structures, it was caught under the jackboot of neocolonialism. Mr Pinto gave me a zero for arguing—like Malhotra—against the sophistry and incomprehensible rantings of rich commies, scuppering my chances of getting a scholarship to study in Britain. I was livid.

I recall another one, a Malayali lady called Renu Elizabeth Abraham, who was what toddy is to Kerala—an unnecessary social evil. When we were learning about the “nationalistic Hinduism” of the Amar Chitra Katha, I asked this doyenne of evangelism whether I could quote Mata Amritanandamayi in my essays. She told me in front of the class, “I am from Kerala. Mata Amritanandamayi is Hindutva. We do not like such people.” It was then that I grasped that students were being indoctrinated against India and Indian culture (both being subjected to argumentative reconnaissance of the kind which was more than careless subterfuge). I cannot recall anymore the layers of political trash of such intellectual carelessness as well as my bête noires who have shaped the way I think, but I will comment on the legacy of historical intervention in this way of moving away from the standard way of doing things.

At Christ University, there was Padmakumar (nicknamed PK by his students) who was a lecturer with a tash. While he was talking about meat eating in the context of Dalit cultures, I was brash in my outburst as my classmates kept quiet…. I told him, “Sir, my Guru has said the difference between animals and plants lies in the difference between having brains and life and having just life. Animals have the former, plants have the latter.” I was a militant vegetarian then who wanted to convert non-vegetarians but failed miserably. I took my own self-aggrandizement with a pinch of salt: “I want to convert at least ten non-vegetarians in my life.” Soon after this, I was summoned to Dean Krishnaswami’s room. He told me snarkily, “You need a Guru.” I sensed he had just read Periyar. In 2022, he and his wife entered the same Murugan temple I visited with my family in my neighborhood in Bengaluru. He prayed as I stared. Surprising? You bet!

I have highlighted some of my experiences at this college because the paper I am critiquing is based on the idea that many gurus abuse their position for sexual gratification. This much is true. The reason is, there are differences between gurus and Gurus, and Amanda Lucia in her paper Guru Sex does not get it. I am Amanda Lucia’s admirer, but there are glaring red flags with which I need to deal. One of them is this: gurus without a capital G are mortals like you and me. They are like the professors about whom I have written, who wield their power over students to serve their ideological mentors. Lucia has focused in her paper on how the binary of teacher and student is similar to guru and devotee, so why not reverse the gaze? Without making a distinction between guru and Guru, Lucia has built an argument based on a supposition. It is not enough to extricate from Hindu guru culture the forms of violence that do exist—you have to analyze and examine the truisms that make it for what it is: a society marred by ethical fractures, just like any other social unit, and that these fractures are spawned by its members’ imperfections. Nobody is a saint except the Guru.

Second, religious groups across the world are situated in scandal. I know Amanda Lucia knows this, but building on the supposition, her paper focuses on gurus who are not at the same level. Nithyananda belongs to the frauds. Period. We have to differentiate between frauds like him and avatars like Amma. Amanda Lucia spent years studying Amma and Her movement but they have gone to waste, as Lucia is incapable of acknowledging that she did experience positive energy when she was with Her, if I recall correctly. That Lucia is unable to make use of her experience proves that she is being scholastic without being scholarly. A scholar who evokes experience goes down to the heart of the matter. Amma Herself says we need to use the heart more than the head, but Lucia’s critique references only head-inspired cerebralism. Lucia’s language is elegant, but she has not engaged with the concern of those who believe in the supremacy of Masters: the media piffle about Them.

When rubbishy Indian and Western media wallahs discuss genuine Gurus, they miss the forest for the trees. This includes those from The Guardian and the BBC whose writers represent the most venal forms of anti-Hinduism in the West. They have ripped asunder genuine gurus like Sathya Sai Baba and Mata Amritanandamayi. I am waiting to find articles on my own Master, Sharavana Baba, who has been in the eye of the storm recently due to malevolent anti-guru activism that Lucia’s tribe speaks of but whose members try to maintain equilibrium with owing to their belief in the validity of “impersonal” social scientific perspectives which mean that the fear that someone will call them “devotees” will betray their true leanings! I was one of them. Being a devotee has become impermissible. I blame the media for it. Anti-guru activists who spend their lives helming video programs and tapping out unsolicited opinions below internet spillage are pure evil. These are the real trolls—those who are terrified in reality but who make full use of anonymity to speak “democratically” hoping their innate Freudian desires get suppressed.

But Amanda Lucia, you are not that. You are careful. I agree. And I will say unhesitatingly: the fact that one of my articles on my own Guru was published by a left-leaning enterprise underscores my point that despite the differences of opinion, the academy does accept submissions from people who attempt to sound interested in current work animated by those who profess. Your linguistic creativity in constructing an argument tied to this enterprise is revealing of your profession—you employ the tools of Western scholarship to drive your point home. This is the nature of your job—I will not steal it from you.

However, using ethnography and participant observation to understand phenomena in the media is so passé. Can it even be done? The BBC’s tawdry documentary on Sathya Sai—”The Secret Swami”—was a cop-out because the Oxbridge director was more preoccupied with the term “godman” than any journalist in the history of filmmaking. Nobody but Gail Tredwell will nod in assent to the use of such language in media work funded by vested interests. Namely, the Church. In the case of my own Guru, I confidently say anti-guru politics have always been the norm in ashrams. People want to denigrate their leaders to gain economic advantages and make noise to compel people to dwell on boring, anti-Hindu projects. Bolstered by those who have no grasp of spiritualism, they seek to bring down the Guru, because who does not love a good scoop? Me!

Which is why I refer to those in authority at the college in which I studied. Christ University is symbolic of all that was wrong with education yesterday (I do not know if the folks there have changed like me in the way I have changed my autobiographical tenses). Their anti-Hindu stances, actions, and postures were disturbing. I was not allowed to speak up for Hindus, and coupled with some of my classmates who were never tired of spouting venom—they eventually got scholarships to study in the UK (duh!)—I realized I should have toed the line so that people would have accepted the quotations in my papers, my verbal diarrhea, my confusion, and my pro-communist (yet Christian!) worldview.

Is this a critique of neocolonialist intentions or a ramble? I do not know. But I will say this: I have come to terms with my past, and if only education were more about the heart than the head, I would die to rewrite it.

The views expressed in this article is the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of India Facts.