Minor Episodes in the Ramayana – Their Sociological Significance

The objective of Vedic seers was to teach the two-fold dharma – that relating to worldly transaction and that relating to liberation. For this they developed three levels of literature in the Indian tradition – the Vedas, the itihāsa/purāṇa-s and the kāvya-s. Each level had its own style of communicating dharma – the Vedas would command like a master, the itihāsa/purāṇa would illustrate like a friend and the kāvyam had the gentle approach of a lover. Itihāsa works on a broader canvas; it has a grand cultural vision for the whole society and wishes to establish a moral and ethical framework by touching various aspects – political, ethical and social. The kāvyam, on the other hand, is on a limited canvas, takes a limited theme and works on it.

Valmiki calls his work a kāvyam, a work of art. Tradition calls it a kāvyam and also an itihāsa. As a kavyam, it has the limited story of Rama, and as an itihāsa, it is larger in size and touches on various topics such as political, ethical and social. The old critical tradition accepted the Ramayana as a guide for ideal living; it happily endorsed its message on a multiple issues and would read it as a pārāyaṇa text. The present critical trend is to study the sociological relations as seen in the text. The Ramayana, whether taken as a kāvya or as an itihāsa, presents glimpses of the society in general by portraying persons of different social strata. Valmiki, with all his Vedic vision, is also a great story teller. He is comparable to a present day screen-play writer because he shows all the minor details of human conduct in his work. This gives us scope to us to examine the body language of the characters, their interpersonal relationship etc.

I wish to examine a few minor characters and study their significance.

The status of Guha vis a vis Rama – Ayodhya kanda, sargas 50, 51

What was the position of the forest dwellers, whom we call tribals now? The character of Guha reveals certain interesting facts.

Valmiki calls Guha a निषादस्थपति, the chief of the hunter tribe. His friendship with Rama is interesting. Rama, along with Sita, Lakshmana, Sumantra and others reaches the village Sringiberapura on the banks of Ganges and wants to halt for the night. Guha is said to be a very dear friend of Rama, dear as his own self – रामस्य आत्मसमः सखा (2-50-33). It is worth noting that he does not inform Guha. Rama shows that a person in distress should not, on his own, go to a friend. It is for the friend to come and console him. Thus, Guha himself, having come to know of Rama’s arrival, comes to meet him with all the elders of his tribe, carrying a variety of food stuff. On seeing Guha, Rama moves up to him. Guha embraces Rama, welcomes him and says – ‘this land is yours. You are our Lord, accept my kingdom and command me as to how I can help you?’ Rama could have happily stayed there but as a kshatriya he has to keep his honour by not soliciting or accepting help from a person, however good the friend may be. Rama, then holds Guha by shoulders and embraces him. “I cannot accept the presents and I will not accept your kingdom. I am here to lead the life of an ascetic. Merely bring fodder for the horses which are tired.”

Why did Rama not inform Guha about his arrival? Rama is the exiled prince and as a person who is not in power he is not sure about the friendship of Guha. It was for Guha to give him re-assurance about his friendship by embracing him. Guha is probably apprehensive about Rama’s intention and hence offers his kingdom to Rama. Along with friendship, there is subtle diplomacy in the behavior of both.

We can observe the social relations here. Rama embracing Guha is a popular scene which we see in several paintings. It is shown as a symbol of Rama’s magnanimity and ability to move even with persons of low social stature. However, we see here that it is Guha who first embraces Rama. The tribal chief was almost on equal terms with Rama, as otherwise, he would not take the liberty to hug Rama.

Commentator Govindaraja discusses whether it was appropriate for Guha to embrace Rama and points out that in those days a tribal chief was even entitled to perform a yajña, which is normally the prerogative of the dwija-s. निषाद स्थपतिं याजयेत् – he quotes the line from the scripture and says that because of this status it is not inappropriate – अत्यन्तानुचितं न भवति इति अनुमन्तव्यम् ।

Here we see that Valmiki is a political observer too. He shows how Lakshmana was managing to be friendly with Guha and at the same time not careless about guarding Rama. He keeps awake all through the night though Guha assures that he and his followers would guard Rama.

On the next morning Guha gets the boat ready for Rama to cross the Ganges. He reports to Rama – “noble sir the boat is ready, kindly get on to that”. Guha in the Adhyatma Ramayana is of a different make. He is a devotee of Rama, the incarnation of Vishnu. He had heard about how a stone was turned into a woman (Ahalya) by the mere touch of Rama’s foot. He requests Rama “sir, your feet had turned a stone into a woman. If, by the touch of your feet my boat turns into a woman, I will lose my livelihood. Let me wash your feet.” In the present text Valmiki does not show Ahalya as a stone. She was merely remaining unseen by people. Guha is a careful tribal chief, conscious of his strength and limitations.

When Bharata reaches the banks of Ganges, Guha welcomes him too, but not before alerting his own followers to be ready with arms. “Bharata will not cross Ganges if he has an evil intention against Rama”, he says, as he was not sure about the intentions of Bharata. He keeps five hundred boats ready with armed men to check Bharata’s army crossing the river. With all this readiness, he approaches Bharata with many presents and food. “This is your servant’s place, please stay here”– he says. After offering food and slowly endearing himself to Bharata he takes liberty to put a friendly question – “I am apprehensive about the army following you. Does it indicate any hostile plan against Rama?” It is a highly measured and diplomatic question. Bharata breaks down, turns emotional and laments for Rama. Guha is then convinced and congratulates Bharata on his noble behavior.

Thus the tribal chiefs had a significant role in the kingdoms of the time. They were like other subordinate kings, with their own territory and people.

There is another reference to the forest dwellers in the Ayodhyakanda. Dasaratha calls for a council of the subordinate kings, tribal chiefs and others, मेच्छाश्चार्याश्च ये चान्ये वनशैलान्तवासिनः (2-3-25). The word वनशैलान्तवासिनः literally means the hill tribes. Their representatives were present in order to endorse the abhiṣeka of Rama as the prince regent. The tribals were very much a part of the Indian main stream culture. Govindaraja mentions the six types of armies in which आटविकं, the forest contingent, is an important component – मूल, भृत्य, श्रेणि, सुहृद्, द्विषद्, आटविकम् इति षड्विध बलोपास्यत्वं सार्वभौम चिह्नं उक्तम् । (2-3-25). Valmiki did not write this for the 21st century liberal intellectuals who wish to theorize that tribals are not part of the main stream. There appears to have been some sharing of power between the tribal chiefs and the kings of those areas. Tribal chiefs ruled their people guided by their own customs while being part of the main kingdom.

Study of Scriptures – who all were included?

The episode of Dasaratha’s curse – Ayodhya kanda, sargas 63, 64

The episode of the young man serving his invalid parents glorifies the virtue of filial piety. In fact, this used to be a story prescribed for school children. The name of the young man is not mentioned by Valmiki but in the other versions of Ramayana it is noted as Sravana.

Dasaratha was a noted marksman and an accomplished archer of his times. He could hit an unseen target by listening to a sound. This art was called शब्दवेधि. In his youthful exuberance he once went for hunting in the forest on the banks of river Sarayu. He killed a few animals by his art of shooting following a sound. He hears the sound resembling that of an elephant gurgling while taking water with its trunk. He shoots a sharp arrow in that direction and hits a young sage who cries out in pain.

ऋषेर्हि न्यस्तदण्डस्य वने वन्येन जीवतः ।

—— जटाभारधरस्यैव वल्कलाजिनवाससः ।। (2-63-27)

को वधेन ममार्थी स्यात् किं वास्यापकृतं मया ।। (2-63-28)

Who is he who wants to kill me, who am a ṛṣi?

Dasaratha is shocked, he moves that person and comes to know of his terrible mistake. The youth narrates the helpless situation of his parents. The young man is groaning in pain as the arrow is stuck in him. He would undergo pain for a long time and die after a lot of torment. He would die more happily if the arrow were to be pulled out. He requests Dasaratha to take to pull out the arrow but the king hesitates.

Dasaratha is in a dilemma whether to pull out the arrow or not. Killing a Brahmin was considered a matter of great sin. He would not hasten the death of the young sage by pulling out the arrow but it was also cruel to allow him to languish. The young sage senses the king’s thought and suggests

न द्विजातिरहं राजन् माभूत्ते मनसो व्यथा । शूद्रायामस्मि वैश्येन जातो जनपदाधिप ।। (2-63-50)

– ‘do not worry because you are not killing a Brahmin. I was born to a śūdra mother from a vaiśya father.’ Dasaratha summons courage and pulls out the arrow and the young sage breathes his last.

Dasaratha approaches the old parents and confesses his terrible mistake. “Oh revered one! I am Dasaratha, the king of this land. Desiring to kill an elephant by the sense of sound and I killed your boy mistakenly. It is a great sin to kill a person doing tapas. Order me as to what I can do”. The elderly parents are shocked. The sage laments for the departed son, recalling the fond memories.

कस्य वा पररात्रेऽहं श्रोष्यामि हृदयङ्गमम् ।

अधीयानस्य मधुरं शास्त्रं वाऽन्यद्विशेषतः ।। (2-64-32)

को मां सन्ध्यामुपास्यैव स्नात्वा हुतहुताशनः ।

श्लाघयिष्यत्युपासीनः पुत्रशोकभयार्दितम् ।। (2-64-33)

“With you gone, I will no more be listening to the sonorous voice of yours in the early hours of every day, when you recite the scriptures for us. Who will console me hereafter? You used to perform sandhyopāsanā, offer oblations into fire and serve us every day”. The sage blesses his son to attain heavenly worlds which are attained by great kings and saints. He then turns towards Dasaratha and pronounces a curse that he too would die wailing over his son. The sage and his wife prepare fire and end their lives.

This episode reveals some important points. The young sage who died was not a Brahmin. In fact he was born to a śūdra woman but he wore matted locks like sages, used to perform sandhyopāsanā and also do the fire rituals. The elderly sage has the power of cursing the kshatriya king.

The commentators Tilaka, Govindaraja and Maheswara Tirtha mention that the person born to a śūdra woman from a Vysya had the authority to perform yajña and also to recite mantras, though in the tāntrika tradition. चतुर्थवर्णस्यापि पञ्चमहायज्ञाधिकारः स्मर्यते, says Govindaraja. Sravana was higher in status and hence eligible to do the above rituals.

We see that the status of a sage was acquired by virtue of tapas and not by virtue of his varṇa. The fact that the father and the son were engaged in tapas raises doubts on the veracity of the episode of Rama killing a śūdra named Shambuka, in the Uttara Ramayanam. Dasaratha showed great reverence to the sage, though he was partly śūdra and partly vaiśya. Rama belonged to the same period and so we cannot visualize him taking up a sword and beheading Sambuka for doing tapas. There could not have been such change in social perception between the time of Dasaratha and the time of Rama. Because of such instances many scholars have pointed out that Uttara Ramayanam could not have been authored by Valmiki.

Here we can make a passing mention of the women in Ramayana doing yajña, reciting puruṣa–sūktam and offering oblations into fires. In the Ayodhya kanda we see Kausalya doing prāṇāyāma and also recitation of puruṣa–sūktam प्राणायामेन पुरुषं ध्यायमाना जनार्दनम् (2-4-33). In the Sundara kanda Hanuman speculates that Sita would come to the brook for performance of sandhyopāsanā (5-14-49). The commentators specifically mention that Sita was sandhyopāsana-tatparā.

A Reference can also be made to Sumantra, the charioteer who drove Rama to the forest and performed sandhyopāsanā in the evening.

उपास्य तु शिवां संध्यां दृष्ट्वा रात्रिमुपागतम् ।

रामस्य शयनं चक्रे सूतः सौमित्रिणा सह ।। (2-46-13).

Shabari – Aranya kanda, Sargas-73 & 74

The popular stories about Shabari show her as a decrepit woman waiting for the arrival of Rama. In her devotional fervor for Rama she is said to have offered the forest fruits to him after biting and tasting them to ensure that they are fully ripe. This is not the version in Valmiki. There is no mention of fruits at all. She merely conducts Rama through the mysterious hermitage of sage Mathanga.

Valmiki introduces Shabari in the very first sarga of the Ramayana as a person well versed in dharma. Valmiki says – शबरीं धर्मचारिणीम् and श्रमणीं धर्मनिपुणाम्. Kabandha advises Rama to visit the hermitage of sage Mathanga near the Pampa lake. Sage Mathanga lived there with his disciples and after a long time of austerities they all ascended to heaven. Shabari used to serve the sage and his disciples and maintain the upkeep of the hermitage. While the sages ascended to heaven they advised her to stay till Rama visited that place. She continued to wait for the arrival of Rama. Kabandha describes her as a परिचारिणी, a servant woman. But she was also a saintly person.

त्वां तु धर्मे स्थिता नित्यं सर्वभूतनमस्कृतम् ।

दृष्ट्वा देवोपमं राम स्वर्गलोकं गमिष्यति ।। (3-73-27)

She is a person in the path of dharma. She is also a person who has done great austerities like her own masters. On seeing her Rama asks –

कच्चित्ते निर्जिता विघ्नाः कच्चित्ते वर्धते तपः ।

कच्चित्ते नियतः क्रोधः आहारश्च तपोधने ।। (3-74-8)

After the formalities of welcoming Rama asks her to show the mysterious hermitage where everything was forever fresh. Valmiki again describes her as – विज्ञाने तां नित्यमबहिष्कृताम् (3-74-19) – a person who was not barred from the knowledge of Brahman. Tilaka quotes an earlier commentator Kathaka – विज्ञाने ब्रह्मविद्यायां मैत्रेय्यादिवत् अबहिष्कृताम् तत्रापि अधिकारिणीम् इत्यर्थः इति कतकः Govindaraja writes – जात्या हीनाम् अपि आचार्यप्रसादलब्ध–ब्रह्मज्ञानाम्. She appears to be a person whom we now call a tribal, as even today tribal people named Sabaras live in the central part of India. The Adhyatma Ramayana specifically mentions that she was a person of lower class. She introduces herself as – “योषिन्मूढाऽप्रमेयात्मन् हीनजाति समुद्भवा”. Such mention is not found in Valmiki but it is hinted that she is a servant woman. Though she did not have the Vedic learning she was not barred from the knowledge of Self. It is because of her power of austerities (तपःशक्ति) that the flowers offered by the sages were still fresh and the bark robes worn by them and left on the trees for drying were still wet. The fires were still blazing from the sacrificial dais. Rama and Lakshmana were astonished to see the place.

After conducting through the ashram she seeks permission to leave for heaven and offers herself into the fire. She rises from fire in a divine form, clad with divine clothes and ornaments and reached heavenly worlds where her gurus had earlier gone.

In this episode we see the following:

- Women to observed celibacy and became ascetics and also took saṃnyāsa.

- They also practiced yoga. Govinda Raja writes – स्त्रिया अपि विदुरादेरिव योगाधिकारः सम्भवति, यज्ञादिकर्मस्थाने गुरुशुश्रूषा । स्वर्गश्च आदौ अक्षयान् इत्युक्त्या पुनरावृत्तिरहितं परमपदम् इति अवगम्यते ।

- All varṇa-s, including the tribals were entitled for the knowledge of Brahman.

- The god (here Rama) is equal to all, he blesses everyone equally.

Mimamsa vs Vedanta – the episode of Parasurama – Bala kanda, sargas 74,75

After completion of the festivities connected to marriage, king Dasaratha takes leave of King Janaka and starts for Ayodhya. The whole retinue of sages and soldiers is with him. The newly married grooms and their brides are in a rejoicing mood. Valmiki introduces Parasurama at this point.

There were frightful screams and cries of birds on the way and the forest animals were also behaving strangely. There was a confusing mixture of bad and good omens seen by them. Dasaratha gets frightened and asks Vasishta about their meaning. Vasishta assures him that there would be a dreadful scene followed by a happy ending.

As they talk, a huge wind storm rises, encompassing the sky with darkness and uprooting the trees. The sun was enveloped in a cloud. From such cloud emerged Parasurama with a battle axe on one shoulder and a huge bow on the other. The sages recognized him and offered due respects. He merely acknowledged them and spoke straight to Rama. “I have heard of your wonderful powers and about breaking of bow. Here is another bow (the bow of Vishnu), equally strong. Brace this string and pull the bow, if you can. I will grant you a duel.”

Dasaratha was petrified by such challenge and tried to plead in an entreating manner but Parasurama ignored him totally and continued to address Rama. He narrates the history of the bow. Speaking haughtily, he challenges Rama to pick up the bow.

Rama accepts the challenge but he is gentle and respectful in his words, partly due to the presence of his father and partly due to respect towards a Brahmin. He takes the bow, braces the string, fixes the shaft and also pulls the bow. He addresses Parasurama “Out of respect for you I do not wish to take your life. The shaft of Vishnu’s bow cannot go waste. I can either impair you by hitting your ability to fly or alternatively hit the heavenly worlds achieved by you by your austerities.” Parasurama realizes that Rama is Vishnu himself and acknowledges as such.

अक्षय्यं मधुहन्तारं जानामि त्वां सुरेश्वरम् ।

धनुषोऽस्य परामर्शात् स्वस्ति तेऽस्तु परंतप ।। (1-76-17)

He chooses to forego the heavenly worlds achieved by him. Rama accordingly releases the shaft and destroys the worlds.

Valmiki’s words are very significant here. He says – “जगामात्मगतिं प्रभुः” (1-77-24). Literally it means that he went in his own way. This would be a very pale interpretation, knowing the nature of Valmiki. Parasurama has merely earned the heavenly worlds which are inferior in nature compared to the knowledge of self. The Isavasya Upanishad declares – “The slayers of self attain the worlds which are demonical, after all (Isa-3)”. A seeker of self knowledge does not aim to achieve such worlds. Self-realization is the highest goal as per Vedanta. Valmiki conveys this message in a subtle way when he mentions in that Parasurama departs for ātma-gati (1-77-24). The word ‘gati’ is also indicative of knowledge, as per the Vedanta tradition. Rama did not hit the ‘gati’ of Parasurama but merely destroyed the worlds. It is a clear message that one should aspire for self-knowledge. What Parasurama does here is precisely the same. The episode could be a reference to the rivalry between the mīmāṃsaka-s and the Vedantins. The mīmāṃsaka-s valued yajña-s and heavenly worlds whereas the Vedantins valued knowledge of the Self. There are other instances in which sages (like Sutikshna) offer the heavenly worlds gained by them to Rama, but Rama gently declines them.

This episode cannot be construed as a power struggle between the Brahmins and the warrior class, as a lay reader may feel. A single soldier with a battle axe cannot wipe out the warriors from the face of the earth. It has only to be understood symbolically. In the earlier episode of the clash between Vasishta and Vishwamitra, we saw that it was a clash between sattva and rajas. It was a spiritual journey of Vishwamitra in which he had to overcome kāma (desire) and krodha (anger). Here, by contrast, Parasurama the Brahmin is displaying rajas whereas Rama is displaying sattva, which is the characteristic of Vishnu.

Valmiki has not portrayed Parasurama as an avatār of Vishnu, though some purāṇa-s have claimed so. The traditional commentators Govindaraja and others have pointed out the purāṇa version too and said that the visit of Parasurama was intended to transfer Vishnu’s energy and glory from Parasurama to Rama. This looks dramatic but Valmiki is silent on this.

The mentoring role of sages

Throughout the Ramayana we see several sages counseling Dasaratha or Rama on several occasions. Sages like Viswamitra, Bharadwaja and Agastya give divine weapons to Rama as they are aware of the future role of Rama in killing the demons.

The meeting with sage Bharadwaja was a testing moment for Bharata. After the introductory formalities, the sage directly asks him “what is your mission in coming to the forest? I hope you do not have any evil intention against the sinless person Rama” (2-90-13). Again, Bharata is crest-fallen. He says – “Your words are like a death blow to me. Please do not apprehend any wrong on my part (2-90-15)”. He further clarifies his innocence.

Sage Bharadwaja hosts a lavish royal dinner to Bharata’s entourage, including the whole army (2-91). By using his spiritual powers he invokes the divine architect to prepare dwelling places for the king and all others. He invokes several rivers to provide a stream of liquors. He invokes several deities to provide choicest food, containing meat of several types. He also summons several divine damsels to entertain the entourage. The sage asks Bharata to rest in the royal mansion. A highly embellished royal throne was ready for Bharata but he visualizes Rama as sitting in the throne and respectfully goes around it and sits in the chair meant for the minister. The army was in merriment but Bharata’s mind was on Rama.

Why did Bharadwaja host a dinner to Bharata, though he gave a frugal dinner to Rama only a few days ago? Probably he wanted to see whether there was any lurking desire in the mind of Bharata for the throne. He saw Bharata respectfully keeping away from it. The sage was also probably demonstrating his spiritual powers, so that Bharata would not deviate from his word. This episode is like a psychological test for Bharata.

Yajña was a dominant feature in social life in the tretā–yuga. (Cf. Mun.Up.) However, seekers of other types, who did not perform yajña-s but who engaged themselves in tapas, meditation, can be seen. They are vaikhānasa-s, vālakhilya-s and others who approach Rama in sarga 6. They see Rama’s ability after killing of Viradha. Govindaraja calls it समर्थकारुणिकत्वम्, the opposite of ineffectual compassion.

Vaikhānasa-s and others were not into yajña but engaged in tapas. It means that the upanishadic thought was coexisting with the yajña and rituals. Perhaps these are the upanishadic sages too. (See the episode of Dasaratha performing the aśvamedha, in which there were śāstra discussions during intervals).

The encouraging and appreciating words of Agastya to Sita (sarga 13 of Aranya kanda) are a psychological preparation for her for the future troubles. In the earlier sarga, Agastya has given weapons to Rama, saying that they would be useful in killing the great asura-s in the mighty battle. Valmiki portrays Agastya as a great psychological counselor. After giving weapons to Rama, Agastya compliments Sita for being a dutiful wife following dharma in an exemplary manner. He also tells Rama ‘your promised tenure in the forest is coming to an end. You will fulfill your word to your father and will get back your kingdom’ (13-15). ‘I tell this out of my special vision due to meditative powers’, he adds. This is a reassurance to Sita. The sage has seen the immediate danger of abduction by Ravana but he has not told it. He cannot say it as he cannot reveal the divine script but act according to it.

If Rama were to merely go back to Ayodhya and rule his kingdom, where is the need for divine weapons? The sages and gods seem to have an understanding of the divine scheme or the divine script in which Rama is a human being who has to be helped by them. The gods give weapons to the sages and the sages give them to Rama. Rama has to be a human so that the boon given to Ravana by Brahma is not violated.

The overall vision presented by the Ramayana is that the ancient society was probably more liberal than what we think of or what our liberal intellectuals would portray. Vedic culture was not the privilege of the few, but large sections of people including vānara-s and rākṣasa-s were included. Several other hints can be found on the relationship among different social groups of the time. We are not sure as to who the vānara-s were. The meaning of vānara is ‘naro vā’, one who makes us wonder whether the person is a human. They were persons with extraordinary strength and they were also extraordinary in size. They, however, followed the same Vedic culture of the time as we can see from Rama’s comments on Hanuman and again from the rituals at the time of coronation of Sugriva. Even the rākṣasa-s in Lanka were reciting the Vedas and performing yajña-s, perhaps in the vāmācāra tradition, as we see in the Nikumbhila episode. It is clear that it was not the clash between the Vedic culture and a non-Vedic culture but it was a clash between good and evil. Sociological inferences can be drawn based on the text but motivated conjectures do not make an honest reading of the text.

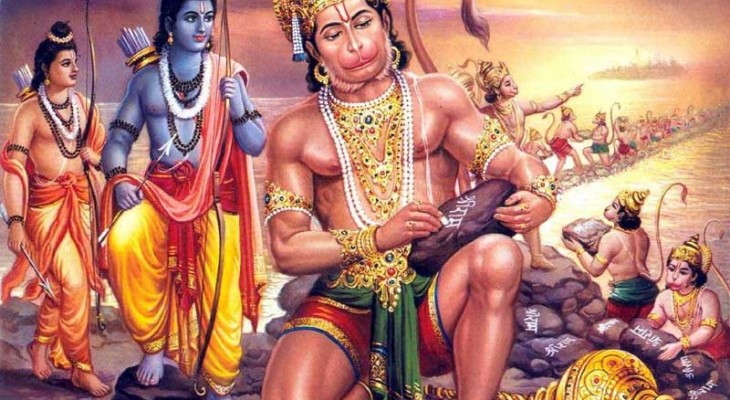

Featured Image: Ram Dass