Origins of Pseudosecularism in Nehru-Patel Rift

Not many people know that the term ‘pseudo-secularism’ originated in the rift between Sardar Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru’s hunger for power and his shenanigans had prevented Sardar Patel from leading the Congress and becoming the the Prime Minister of India despite Nehru losing the party elections to Patel. When the Constitution of India was being framed, Patel insisted against Nehru’s protestations that the right to property be included as a fundamental right. In Hyderabad and Jammu and Kashmir, Patel had used strong methods to solve the problems leading to much bitterness and resentment in Nehru.

It was against this backdrop that the election for the Congress President in 1950 took place. Nehru wanted complete control of the party in order to impose his minority views on the country but faced a hurdle in the form of Patel. While Nehru was a Marxist internationalist who was hostile towards Indian culture, Sardar Patel, a staunch nationalist, was strongly pro-India.

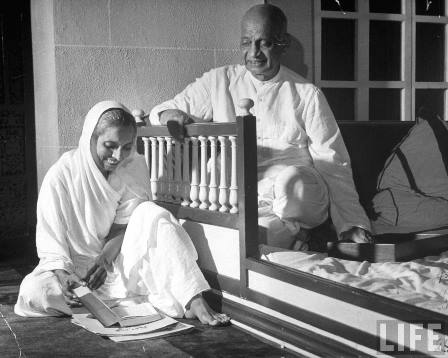

Sardar Patel supported Purushottam Das Tandon for the post of Congress President in 1950. Tandon was known to be a supporter of India and respected Indian culture. He wanted the laws to be equally applied to everyone and was opposed to the appeasement of the people of any religion. In short, he was the polar opposite of Nehru.

Nehru was considered by the international media as a person who, to quote the words of the Gettysburg Times, “suffered from a monumental inferiority complex.” This resulted in Nehru claiming he was an Englishman, and he displayed the same kind of disdain towards Indian people and culture that the English rulers had displayed.

Nehru was intolerant towards Tandon’s personal beliefs and respect for Hindu culture, and in order to oppose him, Nehru supported Acharya Kriplani in the election for the President of Congress. The party election of 1950 became controversial and got worldwide coverage. It was seen as a fight between Patel and Nehru.

As the battlelines were drawn, the elections caused much flutter within the country and each side did its best to get as many supporters as possible. While some units like Tamilnad Congress supported Sardar Patel and Purushottam Das Tandon, others like Mysore Congress were divided. As the stakes were raised, Kengal Hanumanthaiah, a staunch opponent of Nehru and his nationalization of industries, threw his lot behind Tandon. In a closely fought battle, the group led by Tandon and Sardar Patel emerged triumphant.

Unable to swallow the defeat in the elections, Nehru threw a tantrum and refused to join the Congress Working Committee. He eventually joined the Committee after being pacified by more mature people in the party. In allowing Nehru to join the Committee, Sardar Patel and Purushottam Das Tandon had proved that they were statesmen who gracefully accommodated the rebel faction that had lost the election.

Three months after the election, Sardar Patel passed away and Nehru used this event to force another showdown in the party. He used the government machinery to his advantage and got Tandon and the entire Committee to resign. Nehru then reconstituted the Committee and Tandon agreed to serve on it in order to not break the unity of the party when the country was in a nascent stage and it was a period when political instability gave rise to fears of putting the country’s very survival at risk.

This was also the period when accusations of corruption against Congress started coming to the forefront. Nehru followed up his hostile takeover of the party by passing draconian laws against freedom of expression. These laws were specifically targeted at Hindus.

In the wake of these events, Anthony Elenjimittam who was the editor of the Libertarian wrote in his book in 1951:

This superiority of religious realization over pseudo-secularism was proved when Shri Nehru declined to serve on the Working Committee to maintain the prestige of his fashionable secularist creed, while the ‘communal and obscurantistic’ Tandon, in national and patriotic interests, agreed to serve on the very Committee reconstituted by his political opponent, thus practicing the religious principle, as formulated by St. Paul: “Do not be overcome by evil, but conquer evil with good.”

Elenjimittam also decried the hypocrisy of Nehru when he wrote that “the veteran Congress leaders, with Pandit Nehru at the top, continue to shout from the housetops in and out of time about their new fad of pseudo-secularism.”

This was possibly the first usage of the term ‘pseudo-secularism’ in the context of Indian politics. It would be many years before this term seeped into popular culture. The credit for that goes to L.K. Advani who is himself inspired by Sardar Patel. In 1985, in the ruling on the famous Shah Bano case, the Supreme Court castigated the Indian government for doing nothing to make the Uniform Civil Code a reality. A few months later, when the Rajiv Gandhi government used the facade of ‘secularism’ to pass a law reversing the Supreme Court’s decision and legitimized the existence of a parallel Islamic legal system allowing Muslim women to be oppressed, it led to L.K. Advani highlighting the ‘pseudo-secularism’ of the Congress.

As we come closer to the 2014 elections, it appears that it will be 1950 all over again. The forces supporting Sardar Patel seem to be arrayed on one side while those supporting Nehru’s corruption and failed policies are arrayed on the other.

History seems to be repeating itself after nearly sixty four years, but the people of India have the benefit of hindsight over these 64 years to help them arrive at a decision. Every failure in India – the utter poverty of a large section of the population, the loss to China in the 1962 war, India’s failed foreign policy, the division of India’s people along religious and linguistic lines leading to various riots, and the complete failure of Nehruvian Stalinism – can be linked to Jawaharlal Nehru and his policies. On the other hand, the positive characteristics of India and the warnings to guard against various dangers – her unification, the relative economic freedom that briefly put India on the path of prosperity, the prediction about China’s expansionist designs, and the need for India to be self-sufficient and strong – can all be traced to Sardar Patel and his visionary ideals.

[The author can be reached at arvind@classical-liberal.net. Between 2004 and 2010, the author published the ‘4M Report,’ a satirical newsletter with the banner slogan, ‘your regular dose of pseudosecularism.’]