Remembering Jallianwala Bagh: Nadir of colonialism and collaboration

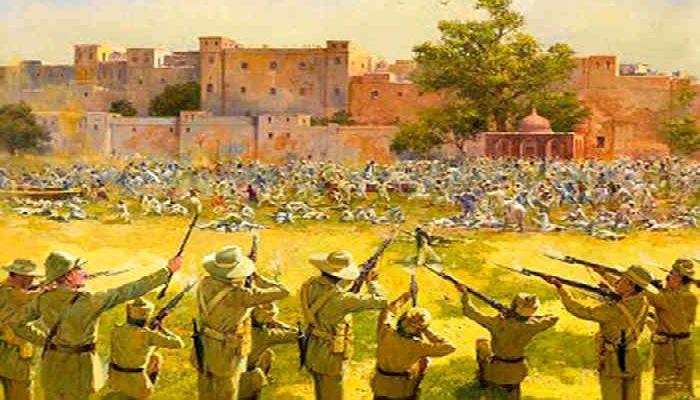

On Baisakhi Day, April 13, 1919, more than 20,000 unarmed men, women and children had gathered at Amritsar’s Jallianwala Bagh. Most had simply drifted into the park to relax after having attended the annual fair in the city; some had come to listen to protestors condemning the arrest and deportation to the Andaman Islands of nationalist leaders Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew who had led an agitation against the draconian Rowlatt Act; very few people in the vast crowd were aware that the British colonialists had declared a ban on public gatherings in Punjab.

At around 4.00pm Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, the head of the British Army’s 48 Infantry Brigade, was informed about a large crowd gathering in the park. Dyer led a handpicked force of 50 soldiers who “would have no compunction at shooting Punjabi civilians”. They comprised 25 Gorkhas and an equal number of Balochs and Pathans. Plus, as escort he took 25 Gorkhas armed with khukris and two armoured cars equipped with machine guns. (1)

Jallianwala Bagh was a 6-7 acre park with just one small exit leading into a narrow bylane where only two people could walk abreast. The moment Dyer arrived outside the park he had made up his mind what to do. He issued no warnings. Since the armoured cars were too large to enter the bylane, he marched the 50 riflemen inside and lined them up on a raised bank less than 20 feet behind the crowd. When the people saw the soldiers line up they began to panic and rush forward but one of the speakers assured them that the British wouldn’t fire and if they did the bullets would be blanks.

Just before 5.00pm, Dyer gave the order to fire. The order was repeated by a British captain named Gerry Crampton, whistles rang out and immediately the troops opened fire.

“Havoc ensued. The crowd ran in terror in all directions but found few exits by which to escape. People crammed into the entrances to the narrow passageways, frantically seeking to force their way out.” (2)

“The troops were directed to fire on these, killing many, and causing more to be trodden underfoot or crushed under the mounds of bodies that eventually built up ten or twelve deep. Many tried to climb the walls, and were picked off as they did so. Crowds huddled in the corners of the garden with no way out at all and were shot down where they stood. Retired soldiers in the crowd shouted out that people should lie on the ground to avoid the bullets, and many did so only to be shot as they lay.” Ironically, these were the same soldiers who had fought for Britain in World War I less than a year ago.

“The firing ceased occasionally, whilst the men reloaded and targets were adjusted, more whistles blew, and firing started again. Dyer ordered reloading after the men emptied their first magazines, then ordered ‘independent rapid fire’, personally directing fire at the densest parts of the crowd. By now the troops were kneeling or lying prone to get the best point of aim.”

Some in the crowd tried to hide behind a well but when the soldiers directed concentrated fire in their direction, many jumped into it, knowing they were certainly going to drown. Over 100 bodies were later discovered in this well. The troops were also targeted to fire at some of the horrified onlookers in the homes surrounding the Bagh.

The firing continued for 10-15 minutes. “The noise in the Bagh was a cacophony of rifle crack, bullets thumping into flesh and walls, ricochets screeching off the brickwork, the screams of 25,000 people in terror and the cries of the wounded….The sight was one of horror. The vast crowd staggered aimlessly; the air filled with dust and blood; flesh flew every-where; men and children fell with limbs broken, eyes shot out, internal organs exposed.” In the midst of this massacre, a British officer named Plomer remarked to Dyer that “he had taught the crowd a lesson it would never forget”. (3)

When Dyer finally decided to stop firing, it was only when his troops had only enough ammunition left to enable them to defend themselves during the march back to their barracks. But even as the soldiers were exiting, Crampton ordered the Gurkhas with khukris to check if anyone was hiding in the drains near the park. The British estimate was 397 dead; the Indian side claimed 1,600 died including 44 children. The ‘unofficial official’ count was 1,800. The youngest among the dead was only eight years old, the oldest was 80.

By the yardstick of British massacres and genocide in India (including the British engineered Bengal Famine that was to come in 1943 and in which 4-7 million Indians would die), Jallianwala Bagh was a small mercy. But because it was the first time that the full extent of British brutality and callousness towards Indian life were observed and recorded in minute detail, Jallianwala Bagh became a symbol of British colonialism.

Left to die

Dyer neither inspected the destruction he had caused nor made any arrangement to care for the wounded. Worse, he ordered a curfew so that the dead and injured were left untended until the following morning. Piteous cries of the wounded asking for water rent the air throughout the night. Many died where they lay overnight.

Dr Bal Mokand was a private practitioner working in the City Hospital, Amritsar, under the Civil Surgeon, Colonel Smith. Three days before the massacre, Smith had started turning away Indian patients calling Indians “badmashes” (ruffians). Any Indian patients who arrived at the hospital were told by Smith to “go to Mahatma Gandhi”. (4)

On April 13, Dr Mokand was part of a team of two doctors and compounders attending over 100 of the wounded. On the next day he attended two wounded persons at their houses. Both had serious fractures needing operations, and he advised them go to the civil hospital. However, they refused, saying Smith was not treating patients properly and was turning them out of the hospital. When Mokand asked Smith’s favourite, Nur Illahi, to intercede for them, Smith accused Mokand of having been at Jallianwala Bagh himself, and berated him for treating those wounded there.

Smith sent Mokand to the railway dispensary, threatening him with flogging if he left it. This was to ensure that those seriously wounded would not receive specialist care. He remained there for a full week without going home even for one night. Smith visited him once, and told him that the official casualty toll for the Jallianwala Bagh had been set at 1,800. He said a lesson would be taught the people and that for every European killed there would be 1,000 Indians killed.

Shrimati Ratan Devi, who spent a harrowing night by the dead body of her husband Chhajju Mal Khatri, described her failed attempt to secure help outside the Bagh after 8.00 pm due to Dyer’s curfew. (5)

Dr Mani Ram, a dental surgeon of Amritsar, lived metres from Jallianwala Bagh, and his stables adjoined it. He found that his 12 year old son Madan Mohan was not at home. He usually played in Jallianwala Bagh, so Mani Ram went to look for him there. He deposed: “I saw a dreadful sight. There were the wounded crying and lying in pools of blood. There were two cows which had been killed as a result of the firing. The dead and wounded were heaped on one another and I had to look for my son among them. Some of the wounded were crying for water. There was nobody to give them water. I was unable to find my son there.” He later returned with his wife and a servant with a large vessel of water, only to find his son dead under a mass of bodies. (6)

Crawling order

Expecting a backlash from the public, Michael O’Dwyer, the Catholic Lt-Governor of Punjab declared martial law in Punjab. In Amritsar, numerous innocent men were rounded up and flogged in public and many were sentenced to death. Among the most hateful orders was that which compelled every Indian who passed along the street in which a Christian missionary named Marcella Sherwood had been assaulted, to crawl on his stomach. Even old, infirm and blind men were not spared and had to crawl the entire length of the street. The British soldiers mercilessly kicked those who raised their buttocks.

Elsewhere in Punjab, innocent people were shot dead in places like Lahore, Gujranwala and Kasur. By O’Dwyer’s orders, aeroplanes were sent to Gujranwala, where they dropped eight bombs and used machine guns to disperse crowds that had assembled, many persons including women and children, being killed and wounded.

In Kasur, people who failed to salaam every white man, were flogged and made to rub their noses on the ground. The biggest six boys were chosen from each school for flogging. All cars belonging to Indians were taken over. (7)

Dyer: Remorseless forever

During his close and prolonged examination by the Hunter Commission, which comprised Indians and Europeans, Dyer remained defiant and brazen: “I had made up my mind. I was only wondering whether I should it or whether I should not do it.” The depth of hatred he harboured in his heart can be measured from his statement: “I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed (the crowd) even without firing.”

The fact is Dyer simply didn’t care. Historian S.R. Bakshi wrote about Jallianwala Bagh: “Unwarranted prejudice of highest degree…It was a heinous crime, nay immoral as well as illegal.” (8)

American academic Stanley Wolpert wrote a novel in which he put thoughts into Dyer’s mind as he makes his way to the Bagh: “Life meant nothing to Orientals, it was cheap, meaningless as the dirt of this disgusting ‘garden’, a filthy field filled with rebellious natives. He’d made up his mind, during the drive over here, to open fire without further warning. He’d given them all the notice any of them could ask for. Much more, in fact, than they deserved. He’d been patient as Job with these vermin. They were a pestilence, a blight defacing God’s earth. They had to be crushed, ground under heel of boot into oblivion. Exterminated.” (9)

At the Hunter Commission hearings, when barrister Chimanlal Setalvad of the Bombay High Court asked whether he would have used the machine guns if he could have driven his armoured cars into the Bagh, Dyer responded: “I think probably yes.”

Setalvad then asked if the casualties would have been higher in that case. Dyer replied, “Yes,” and added, “They had come out to fight if they defied me, and I was going to teach them a lesson.”

In his statement to the General Staff, 16th (Indian) Division, August 25, 1919, Dyer wrote: “I personally had ample time to consider the nature of the painful duty I might be faced with….. There was no reason to further parley with the mutineers, evidently they were there to defy the arm of the law. The responsibility was very great. If I fired I must fire with good effect, a small amount of firing would be an act of criminal folly. I had the choice of carrying out a very distasteful and horrible duty or of neglecting to do my duty, of suppressing a mutiny or of becoming responsible for all future bloodshed. We cannot be very brave unless we be possessed of a greater fear. I had considered the matter from every point of view. My duty and my military instincts told me to fire. My conscience was also clear on that point. What faced me was, what on the morrow would be the ‘Danda Fauj.’ The enemy had given me a fleeting opportunity of suppressing the mutiny there and then, and I must take advantage of it at once or lose it for ever. I fired and I continued to fire until the crowd dispersed and I consider this is the least amount of firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect, it was my duty to produce if I was to justify my action. I would in any case have driven matters to their logical conclusion and continued to fire until the mutineers dispersed. If more troops had been at hand the casualties would have been greater in proportion. It was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowd but one of producing a sufficient moral effect, from a military point of view, not only on those who were present but more specially throughout the Punjab. There could be no question of undue severity. The mutineers had thrown out the challenge and the punishment, if administered at all, must be complete, unhesitating and immediate.” (10)

Christian community: Solidly behind Dyer

After the massacre, the Harvest Field, a missionary journal, pointed out that during the nationalist uprising against the Rowlatt Act, Indian Christians were not found “wanting in loyalty to the (British) Government”. (11)

Marcella Sherwood, speaking on behalf of the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, and Rev Canon Guildford, representing the Church Missionary Society, applauded Dyer’s brutality, saying it was “justified by its results”.

The Christian Missionary Review, describing Gen Dyer as a “brave man”, said his action was “the only means of saving life”.

Missionaries saw nothing wrong in brutality and the massacre, finding them “neither un-Christian not a blot on British rule!”

Bishop Henry Whitehead not only supported the Rowlatt Act but went on to denigrate the nationalist agitation and its leaders as irresponsible and ungrateful.

Another missionary publication, The Young Men of India, heaped praise on Michael O’Dwyer, who forced Indians to crawl before white women, saying that he was “the strongest and best ruler the country has had in modern times”.

Among Dyer’s admirers was the Archbishop of Canterbury, who called him a “brave, public-spirited, patriotic soldier”. In 1920, speaking on a parliamentary motion deploring Dyer’s action, the Archbishop said: “We have undertaken for many years past, in the sight of God and man, to promote the intellectual emancipation of the Indian peoples. We are changing…their habits of thought, their religious ideals and their moral level. We have striven to govern, and are striving to govern, as a Christian nation should; and by a Christian nation I mean apart altogether from the strictly religious aspect of the matter, because we are actuated by the largest, soundest, and deepest principles of Christian civilisation, Christian justice, Christian liberty, Christian encouragement of freedom and of self-control. Because I believe that the pasing of this Resolution by Parliament, and the circulation of it in India and in England, would be taken as setting back these principles in their progress, I ask your Lordships not to vote for it.” (12)

Sikh community: In Britain we trust

Of the 291 Jallianwala Bagh dead whose caste could be identified, only 22 were certainly Sikhs. (13) Extrapolating that figure, less than 8 per cent of the attendees at the park meeting were Sikhs. This is due to two reasons: firstly, Amritsar was a Hindu and Muslim majority city. Secondly, due to the divide and rule policy of the cunning British, the majority of Sikhs had largely stayed away from the freedom movement. In fact, the Chief Khalsa Diwan, the Sikh central governing body, had issued a directive to all Sikhs calling on them to support the government. (14)

The British aim since the 1857 War of Independence, during which Sikhs had remained loyal while Hindus and Muslims had united against the colonialists, was to create schisms between Hindus and Sikhs.

The relationship between Dyer and the Sikhs could be described as a mutual admiration club. He supported the Sikhs both from his conviction that the community was loyal and from his personal affection for them. He protected their Temple, honoured their mahants, cultivated and employed their retired officers and toured their villages. When complaints about British atrocities on civilians were brought to his notice, Dyer took action only when Sikhs needed help.

In turn, the Sikhs saw in him a man who was partial to their side. “They made it clear through him to the government that their community could be relied upon in a way that the Muslims and Hindus could not.”

“The Sikh leaders shamelessly flattered and humoured Dyer.” At a ceremony just days after the slaughter at Jallianwala, Dyer was invited to the Golden Temple by its loyalist mahants for the “almost unheard of honour of being made honorary Sikhs”.

“Sahib, you must become a Sikh even as Nikal Seyn sahib became a Sikh.” The General thanked them for the honour but objected that he could not as a British officer let his hair grow long. Arur Singh, the manager of the Golden Temple, laughed: “We will let you off the long hair.” Dyer offered another objection: “But I cannot give up smoking.” Arur Singh replied: ““That you must do.” Dyer said, “No. I am very sorry but I cannot give up smoking.” The priest conceded: “We will let you give it up gradually.” Dyer neatly sidestepped the matter: “That I promise you, but only at the rate of one cigarette a year.”

The Sikh deification of Dyer is not surprising; in the 1850s they had venerated John Nicholson, a.k.a. Nikal Seyn, a fundamentalist evangelical Scot who hated India so intensely that he enjoyed “flaying alive, impalement or burning” of Indians. He said, “I would inflict the most excruciating tortures I could think of on them with a perfectly easy conscience.” He once made a Pathan chief, who had spat in front of him, lick up his own spittle, and shaved off an imam’s beard while his soldiers held the man down. He called India a barbarous land and believed that his Christian god had called upon the British to civilise it. Nicholson met his end in the siege of Delhi in 1857. (15)

Dyer’s troubled last days

Shortly after the massacre, Dyer was diagnosed with arteriosclerosis. In December 1919 he came down with jaundice which led to a range of health complications – no doubt brought about by the intense stress caused by the criticism of his action and the possibility of dismissal from the army. While posted at Jamrud near Peshawar, he went out for a walk on a cold winter day and returned in terrible pain with gout in the head. He relapsed into sickness and was in and out of delirium for days.

Dyer applied for six months sick leave so he could return to England to recover his health but the army said it could only be granted if he vacated his post. Since Dyer and his wife Annie had been disinherited from the wealthy Dyer family, they were in dire straits financially. Despite his poor health, he had to keep working in the difficult and stressful frontier environment.

Because of his illness, the army indicated that he would not be promoted to Major-General. Hearing this, Dyer became so ill that he could no longer be looked after by his wife and had to be moved to a hospital in Jalandhar. Things were about to get worse.

In March 1920, Dyer was ordered to report to the army commander in chief in Delhi where he was asked to resign his post and that he would not be re-employed in the army. He was placed on half pay. Dyer returned to Jalandhar a broken man and was immediately hospitalised. His health was so severely impacted that he could no longer write his own letters. Dyer and his wife left for England broken and disheartened.

Although left out to hang by the army, Dyer received support from people of British origin and Christians all over the world. He walked away from the disaster he had created a very rich man. The Morning Post, a colonial newspaper in India, started a Dyer fund which gave him £26,000 (Rs 104 million in today’s money). By contrast, each dependent of an Indian killed by Dyer received Rs 500.

The Dyers retired to Bristol where they bought a cottage in the country. However, instead of bucolic bliss, Dyer suffered a stroke which left him incapable of walking. Physical suffering accompanied the daily torture of the mind. The demons of Amritsar haunted him day and night and he would try to drive them out by constantly reading books. When his eyes became too tired he would ask his wife to read aloud to him. During the pauses he would repeat like a madman that he had “only 80 men against something like 20,000 Indians”. But he never admitted to making a mistake. (16)

After five years of relentless nightmares, Dyer suffered another stroke on July 10, 1927, which left him speechless; it seemed like even nature wanted to shut him up. He died two weeks later.

His wife Annie led a soulless existence till her own death. She was reduced to writing letters to newspapers to redeem her husband’s reputation, including a letter to the Daily Telegraph against propaganda released by Germany’s Nazi Party magazine 12-Uhr Blatt, which used the Amritsar massacre to pour scorn on the British rule in India. (17)

Fate of Michael O’Dwyer

Like Dyer, O’Dwyer too received his own fund, towards which some of the Punjabi elite like Kunj Bihari Thapar (the grandfather of journalist Karan Thapar), Umar Hayat Khan, Chaudhary Gajjan Singh and Rai Bahadur Lal Chand contributed Rs 1.75 lakh.

O’Dwyer was assassinated on March 13, 1940 by Udham Singh, an Indian freedom fighter, who pumped six shots into his heart. During his trial Singh stated: “I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it. He was the real culprit. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him. For full 21 years, I have been trying to seek vengeance. I am happy that I have done the job.”

Udham Singh, who took the name Ram Mohamed Singh Azad as a symbol of India’s unified resistance to British rule, was hanged on July 31, 1940. His remains are preserved at the Jallianwala Bagh memorial. (18)

Sources

- Nigel Collet, The Butcher of Amritsar, page 256

- Nigel Collet, The Butcher of Amritsar, page 259

- Hunter Commission Report, Evidence, vol iii, page 41

- Depositions for the Witness, 90-93, National Archive, Kew, O’Dwyer v. Nair, Supreme Court of Judicature, Depositions – Exhibits Taken off the File, 16 January 1924

- 17/634, Depositions for the Witness, 123, National Archive, Kew, O’Dwyer v. Nair, Supreme Court of Judicature, Depositions – Exhibits Taken off the File, 16 January 1924

- 17/634, Depositions for the Witness, 115, National Archive, Kew, O’Dwyer v. Nair, Supreme Court of Judicature, Depositions – Exhibits Taken off the File, 16 January 1924

- Jawant Singh, The Tribune, https://www.tribuneindia.com/2002/20020413/windows/main1.htm

- R. Bakshi, Jallianwala Bagh Tragedy, page 42.

- Stanley Wolpert, Massacre at Jallianwala Bagh

- Dyer Papers, National Army Museum, pages 4-5

- Kanchan Gupta, The Pioneer, 13 July 2014, https://www.dailypioneer.com/2014/columnists/2014-07-12-4113.html

- Punjab Disturbances, HL Deb 20 July 1920 vol 41 cc311-77, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1920/jul/20/punjab-disturbances-the-case-of-general

- Nigel Collet, The Butcher of Amritsar, page 292

- Nigel Collet, The Butcher of Amritsar, page 290

- The Spectator, https://www.spectator.co.uk/2018/11/the-lion-of-the-punjab-the-short-brutish-career-of-john-nicholson/

- Bristol Times, July 22, 1927

- Daily Telegraph, November 19, 1938

- India Today, https://www.indiatoday.in/fyi/story/shaheed-udham-singh-the-man-who-single-handedly-avenged-jallianwala-bagh-massacre-1300988-2018-07-31

Featured Image: Aparajita