Sources of Hindu Dharma – I

In Hindu Dharma, the following four are considered the most authoritative sources of Dharma – the Vedic scriptures (Shruti), the Smriti scriptures, the good practices followed by the virtuous or traditional practices that are good (Sadāchāra), and one’s own judgment and conscience (Ātmanas-Tushti). The Vedic scriptures are considered the most important authority because they are said to be of Divine inspiration, and all other sources are successively of lesser authority than the preceding ones.

If one gets confused as to what is good and what is wrong, then we can consult a knowledgeable and pious Guru for first hand guidance. Distinction between good and bad can be very confusing, and therefore one should try to understand and learn about as many sources of Dharma as one can.

In Praise of Dharma

Artha and Kāma must be pursued only in accordance with the principles of Dharma. Secondly, Dharma also lays down the foundation on which one can start proceeding towards the final goal – Moksha. Therefore, Dharma should play a pivotal role in our lives. Hindu scriptures give the following verses praising Dharma, and describe its importance:

| The Earth is supported by Dharma. Atharva Veda 12.1.17

After we die, neither the father, mother, son, wife nor one’s clan is available for help. Only the Dharma that one has practiced in his lifetime before death is present to help us out. Manusmriti 4.239 When Dharma is destroyed, it destroys us. When Dharma is protected, it protects. Therefore, do not injure Dharma, lest the injured Dharma strikes us back. Manusmriti 8.15 The person who knows Dharma and also follows it is called ‘Dhārmika’. Such a person becomes famous in this world, and goes to heaven upon death. Vasishtha Dharmasutra 1.2-3 Luxuries such as wealth and a handsome body do not last for ever, but death lurks nearby always. Therefore, one ought to accumulate virtue at all times. Vyāsa Smriti 4.19 Everyone dies one day, but the man who performs many virtuous deeds does not really die (because his fame lives even after his death). In contrast, a man who has never done great and pious acts dies the death of a donkey (i.e. his life was a waste and he dies unsung). Vyāsa Smriti 4.25 Man must go to the abode of death all alone. He must bear the punishments alone. Hence, it is he who must perform pious deeds. Vāyu Purāņa 2.14.29 None follows him who proceeds along the path of death. Only the actions performed by him accompany him. Vāyu Purāņa 2.14.30 If a person is defiled in his inner emotions, all his external actions never bear fruit even if he puts in his utmost effort. Vāyu Purāņa 2.8.182 Even if a person donates all his possessions, but has an impious inner soul, he will not be considered perfect. Dharma alone is the true cause of perfection. Vāyu Purāņa 2.8.183 |

The Sources of Dharma

1. Shruti: The Vedas constitute the Shruti, which means ‘that which has been heard (from God) by the Rishis’ and are considered of Divine origin[1]. The principles of Dharma that are taught in the Vedas are called the ‘Vaidika Dharma’ or ‘Shrauta Dharma’ and are considered to be infallible (without error), universal and eternal. Certain kinds of religious acts are prescribed only in the Vedas, such as performance of yajnas, and these are specifically considered as Shrauta Dharma[2].

| Dharma has been preached only for those who are not addicted to Kāma and Artha. And for them who desire to know Dharma, the Vedas are the supreme authority. Manusmriti 2.13 |

In keeping with its eternal and universal nature, the Shruti does not have many instructions of ‘do this’, and ‘don’t do that’ nature (except when talking about universal virtues and spiritual truths) because such instructions tend to be non-universal by their very nature.

For example, the Vedas do not command us to ‘wear a coat made of fur’, because such a command could not be followed easily by the people in tropical countries very easily. Rather, the Vedas will just give a general command like ‘wear decent clothes to protect your body’.

2. Smriti: This word literally means ‘that which is remembered’. Human culture advances when the collected wisdom of the society is passed on from one generation to another (‘societal memory’), and each new generation adds to its inherited wisdom. Whereas Shruti is considered of divine origin or inspiration, Smriti is considered the wisdom of Saints and Sages who were pious, virtuous and had understood the Vedas. It is believed that the teachings of Smritis are derived from the Vedas itself.

The main Smriti texts which teach about Dharma are the ‘Dharmashastras’, and therefore, the word Smriti itself is sometimes taken to mean the Dharmashastras alone. However, many other Smriti scriptures teach about Dharma, examples of such scriptures being the Purāṇas, Mahabharata, and Ramayana and so on. Certain types of Dharma, such as the duties of Varnas (Social classes), Jatis (Castes) and Ashramas (states of life) are specifically taught in detail only in the Smritis, and are therefore called Smārta Dharma2. Smritis give a practical twist to the principles of Dharma that are taught in the Vedas, so that people in different periods and regions can apply them easily. For instance, the Smriti will ask us to wear clothes of specific materials depending on the climate of a particular region. Likewise, a Smriti based in a particular geographical area (say the state of Kerala, which is very close the equator) will ‘acclimatize’ its teachings to hot climate. Similarly, some Smritis are said to be applicable to one particular period of time, others at another period of time.

It must be emphasized that the Shruti and the Smriti are considered the two most important means to decide what is correct and what is wrong. These scriptures are either perceived by Rishis in a state of meditation and are of Divine origin, or they reflect the person wisdom of the Rishis. This is the reason for their importance. In contrast, decisions and writings of ordinary people like us are not as authoritative. As a scholar says:

“An impure mind, no matter how intelligent, has many limitations. It cannot know anything beyond the domain of sense perception or what lies beyond the world of time and space. It cannot know what is going to happen the next moment, or what happened in the distant past. Metaphysical truths, such as the knowledge of the existence of God or the hereafter are beyond the scope of such a mind. But when that same mind is purified or transformed through spiritual discipline into an extraordinary mind, it can transcend the barriers of the sense world and reach the outermost frontier of the world of time and space. It can then glimpse what lies beyond the domain of the senses. It gains extraordinary capabilities. It becomes all-knowing; it can know all the events of the past, present and the future. A genuine saint possesses such a pure mind. With the help of that mind the saint comes to know the truth about God, the soul, creation etc. Such truths are called super sensuous or metaphysical truths. Hinduism, like other major religions, is based on such truths discovered by its pure-minded sages.”[3]

3. Sadāchāra or Shishtāchāra: This means virtuous conduct or good practices of people who know and understand the Vedas. Sometimes, when Shruti and Smriti do not offer us any guidance on what is right and what is wrong, we have to rely on the ideals or examples set by other pious Saints and Sages, or behavior of communities/groups known to have very high ethical and moral standards in accordance with the teachings of Shruti and Smriti. Such exemplars or ideals whom we should follow are called the ‘Shishtas’. It is very easy to get mislead by others’ conduct because we might think of an evil person as a good person and vice versa, or we might consider good conduct as bad conduct or vice versa. Therefore, Hindu scriptures define who the Shishta is and what Sadāchāra or Shishtāchāra really mean:

| If there is any doubt in you as to what is the proper conduct, then you should follow what those Brahmans who are competent to judge (right from wrong), are devoted (to good deeds), are not lead (blindly) by others, are not harsh and lovers of Dharma would do in such cases. Taittiriya Upanishad 1.11.4

A shishta is one who is free from envy and pride, possesses just a jar of grain (for sustenance, i.e. he is not greedy and does not hoard wealth), is free from covetousness, hypocrisy, arrogance, greed, delusion (or folly) and anger. As it has been said- “Shishtas are one who have studied the Veda with its supplementary sciences per the correct procedure, who know how to draw inferences from them and who can quote statements from the Vedas as proofs for their recommendations on Dharma”. Baudhāyana Dharmasutra 1.1.5-6 (similar to Manusmriti 12.109) On the failure of the Shruti and Smriti in deciding on Dharma, Shishtas are the authority. A shishta however is one whose heart is free from (worldly) desires, and only those examples from the lives of shishtas are considered as Dharma for which no selfish cause or motive can be assigned. Vashishta Dharmasutra 1.5-7 The following 8 activities are also characteristically Shishtāchāra viz. charitable offerings, truthfulness, austerity, knowledge, learning, sacrifice, renunciation of the world and departure from one’s household and sympathy. Since the Shishtas- Manu and the 7 Rishis (Saptarshis), practice these in all the Manvantaras, they are therefore declared as Shishtāchāra. Brahmāṇda Purāņa 1.2.32.41b-42a The word ‘sat’ means good, and the good are those who are free from (moral) taint. The practices of such people are called Sadāchāra. Vishnu Purāņa 3.11.3 |

Shishtas are living examples of the teachings of Shruti and Smriti. Therefore, our scriptures teach us that we should try to keep company with them if we wish to elevate ourselves morally and spiritually. The company of such Shishtas is called ‘satsanga’.

Sadāchāra is a very important source of Dharma because most of us are not well read either in the Shruti and the Smriti. Moreover, it is often difficult to understand these scriptures. The easiest way for us to figure out the correct way is to therefore see what a Shishta, Sant or a Rishi did in that situation. This is because the lives of these holy men and women are the manifest examples of the teachings of Shruti and Smriti. However, some people spend a lot of time reading about the lives of Sants but do nothing to incorporate their examples in their own lives. The correct way to learn from Sadāchāra is described in the following story:

Pandit Gurudutt was a close associate and confidante of the Swami Dayananda Saraswati (1824 – 1883 CE). After the Swami passed away, some followers urged Gurudutt, “You knew the Swami very well. Why not write a biography of him? It will bring you great fame.”

Pandit Gurudutt replied, “Yes, I am actually writing a biography of Swami Dayanand. I have started work on it.”

One of Swami’s followers asked, “Well, that is wonderful. We shall await its completion. Do you know when you will complete the biography?”

Pandit Gurudutt replied, “Let me clarify one thing right now. I am not writing a biography using pen and paper. Instead, I believe that the best way of writing a great man’s biography is to follow his teachings and life, and live like he did. I have started emulating his examples, his teachings and his actions. Let us see how long it will take me to become like him.”

4. Ātmapriya or Ātmatushti: Most scriptures allow only the first three sources of Dharma[4], but some scriptures such as Manusmriti[5] allow this fourth category called ‘Ātmapriya’ that ‘that which one prefers to do’. A close English equivalent of this term would be ‘conscience’.

| Differentiate between what is right and what is wrong correctly by using your intellect. They who are highly intelligent individuals can use proper reasoning to determine what is good and what is evil. Rāmāyaṇa 3.66.16

The principle of deciding what is Dharma is subtle. Abiding within the hearts of all living beings, the ātman alone knows what is good and what is evil. Rāmāyaṇa 4.18.15 |

This source of Dharma is resorted to when

- We are faced with a moral or an ethical dilemma, and the Shruti and Smriti are unable to provide guidance, and there is no good recommendation available on what is good and what is bad even from the precedents from the lives of Saintly men. In such a situation, we are left with no option but to follow what our conscience, molded by our own understanding and practice of Dharma advises us to do.

- A second situation where one should follow our conscience or what appeals to oneself is where the scriptures of equal authority provide multiple alternatives from which one can chose according to one’s own preferences.

- Ātmatushti does not mean ‘anything goes’ or that we can do whatever we like! The Hindu scriptures clearly say that it is only the conscience of the virtuous, cultured and learned people that matters, not that of evil doers.

5. Noble Resolve: According to a Dharmashastra[6], a resolve that originates in a noble desire or intent (‘samkalpa’) also constitutes Dharma even though it might not have any basis in the first four sources of Dharma. For e.g., one may resolve to narrate light hearted jokes to liven up the mood of a sad group of people.

Hindu scriptures are very clear that this type of resolve should be guided by virtues like truth, compassion, charity etc., and not by negatives like prejudice, hatred, and excessive attachment and so on.

6. Long Standing Traditions of one’s family or community: This often appears to be the easiest way to guide one’s behavior because such traditions are handed down from one generation to another with our own families, so that we observe them every day and imbibe them automatically. Hindu scriptures encourage people to follow traditional customs of one’s family and society.

| One should walk in the path of good men which their fathers and grandfathers trod. By doing so, one will come to no harm. Manusmriti 4.178

Manu has declared that the peculiar customs of countries, castes and families may be followed in the absence of rules propounded by the Veda. Vashishtha Dharmasutra 1.17 |

The Dharmashastras also recognize the fact that many religious practices and learning that women and men of lowers castes possess are not necessarily well documented in the Smriti literature. Such learning is elevated to the status of a supplement of the Atharva Veda, and everyone is exhorted to learn this wisdom too.

| The knowledge which Shudras and women possess is the completion (of all study, i.e., study is completed only after learning this knowledge).

They declare that (this knowledge) is a supplement of the Atharva Veda It is difficult to learn Dharma from the Vedas alone, but by following the practices that reflect the teachings of the Vedas, this learning is easily acquired. The practices reflecting the teachings of Vedas are the conduct that is universally followed by men of the three twice born castes (Brahmans, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas) in all countries who have obeyed their teachers completely, who are elders, whose senses are under control, who are not greedy or deceitful. In this way, he will win both this world and the next. According to others however, the remaining duties should be learned from women and men of all castes. Apastamba Dharmasutra 2.2.29.11-15 |

Many of these conventions and customs manifest in our day to day lives as local festivals, visiting local temples and other holy places, revering a local saint, performing worship to a family deity and so on. Therefore, the Dharmas included in this category are often described by terms like ‘deshāchāra’ (conventions or customs of the region or country), kulāchāra (family or clan traditions), ‘jātidharma’ (specific duties of one’s caste) and so on. Sometimes, this source of Dharma is just subsumed under the category of Sadāchāra, but the difference is that Sadāchāra is of more universal application and has a more universal nature.

To be Continued …

Notes

[1] The word ‘Rishi’ is derived from the Sanskrit root ‘Drish’, or ‘to see’. In other words, the Shruti is the record of the spiritual vision, or insight into the Divine of the Rishis.

[2] Matsya Purāņa 144.30-31; Vāyu Purāņa 59.31-32

[3] Swami Bhaskarananda, pp. 3-4

[4] Baudhayana Dharmasutra 1.1.1-4; Mahabharata 3.207.83; 13.141.65; 12.354.6

[5] Manusmriti 2.6 and 2.12

[6] Yajnavalkya Smriti 1.7

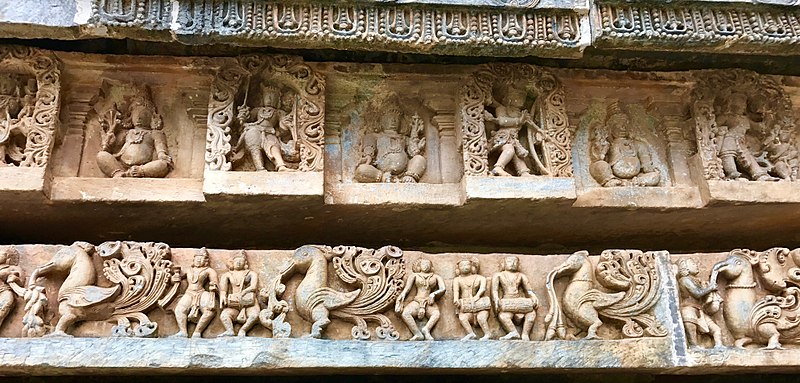

Featured Image: 12th-century Kama Artha Dharma Moksha relief at Hoysaleswara Temple in Halebidu Karnataka (Wikipedia)