The Kerala Story: A Repeat of Muslim Concubinage, Seduction, and Violence

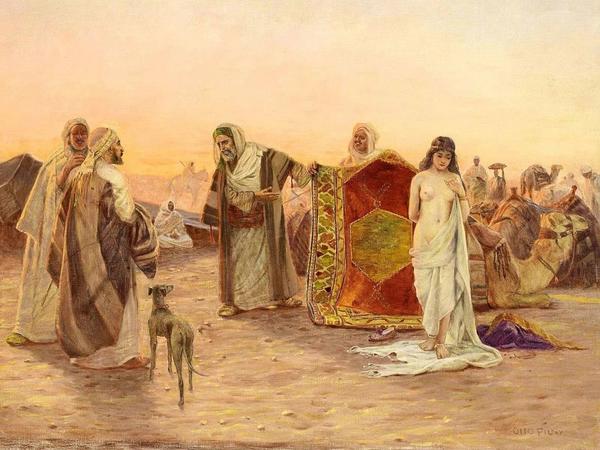

Image Courtesy: blogtalkradio.com

Release of the film, The Kerala Story, in May 2023, invigorated public discussions on the issue of “Love Jihad”. Derided as a “conspiracy theory” in several quarters, this term was in fact part of a 2009 Kerala High Court Order. In Shahan Sha A. vs. State of Kerala, the High Court had directed Central and State Governments to enquire into “Love Jihad” or “Romeo Jihad,” a campaign propagated by Muslim organizations to convert girls to Islam under the pretext of love (1). Soon after, the Catholic Church in Kerala circulated guidelines amongst all Churches and Church-managed educational institutions to help parents and teachers protect female students (2). In 2010, then Kerala Chief Minister V S Achutanandan expressed concern that there was a plan to Islamize Kerala in twenty years using “money and marriages” (3).

The Kashmir Files (2022), similarly revived public discussions about the long night of January 19, 1990, in the Kashmir Valley, when there were calls from loudspeakers to turn Kashmir into Pakistan, bereft of Hindu men but with Kashmiri Pandit women accommodated for the use of Muslim men (4).

Bangladesh set up an International Crime Tribunal (ICT) in 2009 to investigate abuses committed by the Pakistan Army during the 1971 Liberation War (5). In its judgments, ICT held the personnel of the Pakistani occupation army and its local para-militia responsible for the rape of Hindu women with discriminatory intent (6).

In his path-breaking 1946 work, Pakistan or the Partition of India, Dr Ambedkar wrote that Muslim law permitted both polygamy and concubinage. There was no limit to the number of women slaves a Muslim man could cohabit with, without any obligation to marry (7). While elaborating on how the character of the North-Western region changed over a millennium, Dr Ambedkar referred to the first successful Muslim invasion of India. This was in 711, when the Arabs, led by Muhammad bin Qasim, defeated Raja Dahir of Sind. Temples were looted and the booty was divided equally among soldiers after the one-fifth “legal” portion for the king was set aside. Brahmins, above the age of 17, were put to death. All others, along with women and children, were led to slavery (8).

The painful experience of medieval India with slavery is just one of the many tragic episodes in Indian history, which were air-brushed away in the post-1947 history textbooks, in the name of promoting social cohesion and national solidarity. Despite the opprobrium which followed, some die-hards still ventured where only fools would dare and managed to publish works backed by evidence, which challenged these ideologically colored “government-approved” historical narratives.

Kishori Saran Lal (K.S. Lal), who was appointed as the Chairman of the Indian Council for Historical Research (ICHR) in 2001, was the author of several books on the medieval history of India. A well-regarded professor of history, he earned the moniker of a “communalist” from the Left-Marxist-Islamist historians soon after his 1973 book Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India, hit the stands. Lal wrote in his 1999 work, Theory and Practise of Muslim State in India (9) that the so-called “eminent historian” Irfan Habib criticized his book in 1978.

*****

Muslim Slave System in Medieval India

K.S. Lal’s Muslim Slave System in Medieval India was first published in 1994. Lal makes a reference to the prevalence of slavery in all ancient civilizations — be it Greece, Rome, or Egypt. Slaves in ancient Indian society were treated with much more consideration. In fact, Megasthenes who visited India during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya, found the treatment of slaves so mild compared to other countries, that he wrote that all Indians are free. None of them is a slave, he said. Slavery continued in Europe, after the rise of Christianity to power in the Roman Empire. The Church fathers and Popes sanctioned slavery on scriptural grounds. Many churches continued to support slavery right up to the Civil War in the US (1861-65). In Arabia, the Prophet Muhammad continued the prevailing practice of taking slaves. He urged the faithful to enslave non-Muslims. The share in the loot from war, which included slaves, and the profit obtained through the sale of slaves, added a new zest to the practice of slavery. The outcome in due course in the medieval Islamic world was the emergence of big slave markets in Muslim capitals such as Medina, Damascus, Cairo, Bukhara, Ghazni, and Delhi.

He mentions that Quranic injunctions, Islamic conquests, and Muslim administrative institutions gave both legitimacy and continuity to the slave system. In Arabia, it was the norm not to treat slaves harshly. As the slave system developed wherever Muslim rule was established, these restraints were not always observed though. Various chapters in the book provide a comprehensive description of various aspects of the Muslim slave system, its practice, and its politics, along with how it both impacted and was influenced by the ebbs and flows of the various Muslim dynasties in medieval India.

The terrible suffering that the victims would have endured, and which quite naturally finds a very limited mention in the Muslim chronicles of the time, does not escape Lal’s attention. He highlights a fifteenth-century work Kanhade Prabandha, composed in the mid-fifteenth century, in old Rajasthani or Gujarati. It records the valor of King Kanhardeva of Jalor against Alauddin’s General Ulugh Khan who had attacked Gujarat in 1299 and had taken several prisoners. Their agony as they were paraded under the blazing sun and in the cold of the night (likely in the Rajasthan desert), is described in heart-rending detail. This also helps one get a sense of how dehumanizing captivity slowly corroded the will of hitherto brave warriors, who then resigned themselves to their fate as slaves. Fortunately, the chained in this instance, were rescued by Kanhardeva after a hard-fought battle.

The last chapter of the book focuses on sex slavery, which shall be taken up in some detail. At the two ends of the Muslim rule in India were Muhammad bin Qasim’s invasion of Sindh in 712 and the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761. The enslavement of women and children, post-Qasim’s bloody plunder of Sindh, has already been discussed. 1761 was not much different either. The prisoners were paraded in long lines. Many were beheaded. Some of these had held the highest rank in the land, before Panipat. Women and children who survived were enslaved. Forced marriages, which in a zest for euphemism, came to be called “matrimonial alliances,” and became common throughout the medieval period. In his memoirs, Mughal emperor Jahangir writes that in the third year of his accession, he demanded in marriage the daughter of Jagat Singh, eldest son of Raja Man Singh (of Amer). Such description is not used while describing Nur Jehan, his chief consort.

In the homes of Muslim ruling classes, these wedded women were not treated better than concubines or slave girls. Deval Devi was the daughter of Raja Karan Baghela of Gujarat and his queen Kamala Devi. The queen was captured in the sack of Gujarat in 1299 and married to Allaudin Khilji. Kafir women could be married to Muslims even while their husbands were alive, as in Islamic law the marriage stood annulled after captivity. Deval Devi was captured in another campaign in 1308 and married to Allaudin’s son Khizr Khan, who was later assassinated. She was then married to Qutubuddin Mubarak Khalji (1316-20), against her will. After Khalji’s murder by Khusrau Khan, she was taken into Khan’s harem. Princess Deval, tragically, was just transferable property in the ruling House of Khalji.

The children of concubines were free, but the status of concubines was no more than being the mother of her children. Hindu concubines had little influence on the psyche of their Muslim children. For example, the mothers of both Sultan Firoz Tuglaq (1309-1388) and Sultan Sikandar Lodi (1489-1517), were Hindu. However, their reign was marked by bigotry.

While marriages brought servants, it was the raids that yielded a rich bounty of slave girls. The usual policy was to kill able-bodied men and enslave the women, who were then distributed among nobles and soldiers. Ibn Batuta (1304-69) wrote that during the reign of Muhammad Bin Tuglaq, girl slaves were distributed on a large scale during festivals like Id. First, the daughters of kafir (Hindu) kings captured during the year, sang, and danced. They were gifted to Amirs and important foreigners. Then, the daughters of the other kafirs danced and were given away to the Sultan’s relatives. On the next day, female singers were distributed among Mamluk Amirs.

Once it was known that the men had been killed and that the kingdom had fallen, many women came to practice self-immolation (Jauhar), to escape their cruel fate as concubines. On February 23, 1568, Rajput commander Jaimal fell to Mughal Emperor Akbar’s army. Soon after, flames broke out from various places in the fortress. As many as three hundred women were believed to have embraced fire.

After the demise of Aurangzeb in 1707, Muslim power in India started to wane. This slowly led to a resource crunch in the harems of royalty and nobility. The ensuing financial hardship forced many girls to leave their harems and fend for themselves. Many of them became dancing girls and prostitutes.

The harems of medieval India started to become a distant memory.

*****

Muslim System of Slavery after the Middle Ages

The Muslim system of slavery did outlive the Middle Ages though. In the post-script to the book, Lal writes that in 1855 the Ottoman Empire ordered the governors of its distant provinces to ban slave trade. The Arab leader Shaykh Jamal (who even otherwise had a rebellious track record), denounced the ban as contrary to Islamic Law. He declared that it was lawful to kill Turks and to enslave their children. After the Ottoman Turks succeeded in suppressing the rebels by mid-1856, as a concession, Hijaz (in present-day Saudi Arabia) was exempted from the 1857 decree outlawing trade in black slaves throughout the rest of the Ottoman Empire.

Slavery was eventually abolished in Saudi Arabia in 1961.

*****

Conclusion

“Forced conversions and Forced marriages in Sindh, Pakistan,” a 2018 study carried out by the University of Birmingham, cites a report by the volunteer group “Responsible for Equality and Liberty,” which estimates that between 20 to 25 Hindu girls are forcibly converted every month. The abducted victims are often subjected to sustained emotional and physical abuse, including threats to their loved ones. Both personal beliefs and fear of reprisal from extremist elements influence judicial officers to accept the claim that the woman/girl converted of her own free will. Some organizations, like Minhaj-ul-Quran, offer rewards for successful conversions. They say it is the equivalent of Haj-e-Akbari, the greatest duty of Muslims (10). In 2021, the Minister of Religious Affairs in Pakistan opposed a restriction on religious conversion before the age of 18 years, saying that if someone aged 14 years wished to convert, they could not be stopped (11).

For those who feel despondent in the midst of all these attempts at conversions through force, fraud, and inducement, all in the name of adherence to a holy scripture, history offers a sliver of hope. The interpretation of the tenets of a holy book is often more flexible than it seems at any given moment. We hope that the suffering of women, whose only crime is that they were born “unbelievers,” may soon become a part of historical lore, as have the harems of medieval India.

*****

References

- Shahan Sha vs. State of Kerala, December 9, 2009. Indiankanoon, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/576406/

- Union of Catholic Asian News (October 13, 2009). “Church, state concerned about love jihad” —https://web.archive.org/web/20091018162826/http://www.ucanews.com/2009/10/13/church-state-concerned-about-love-jihad

- Times of India (July 26, 2010). “Kerala CM reignites ‘love jihad’ theory,” https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/kerala-cm-reignites-love-jihad-theory/articleshow/6216779.cms

- Col. Tikoo, & Dr. Tej Kumar (March 13, 2022). “Kashmiri Pandits offered three choices by radical Islamists,” India Defence Review, http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/kashmiri-pandits-offered-three-choices-by-radical-islamists/

- Wikipedia. “International Crimes Tribunal (Bangladesh),” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Crimes_Tribunal_(Bangladesh)

- Islam, Rafiqul (1979). National Trials of International of International Crimes in Bangladesh: Transitional Justice as Reflected in Judgments. Brill Nijhoff. Page 173-175.

- Ambedkar, B.R. (1946). Pakistan or the Partition of India. Kindle Edition. LOC 4813

- Ambedkar, B.R. (1946). Pakistan or the Partition of India. Kindle Edition. LOC 981-1040

- Wikipedia. “K.S. Lal,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K._S._Lal

- Ackerman, Reuben (2018). “Forced Conversions & Forced Marriages in Sindh, Pakistan”. CIFORB, The University of Birmingham, p. 1-2, https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-artslaw/ptr/ciforb/forced-conversions-and-forced-marriages-in-sindh.pdf

- Gurmani, Nadir (July 14, 2021). “Religious Affairs Ministry opposes Restricting Religious Conversion before 18 Years of Age,” Dawn, https://www.dawn.com/news/1635052