A Vedic Aryan Homeland in the Steppes? A Critique of the Kurgan Hypothesis

In this brief post, we look at the Kurgan hypothesis of Indo-Aryan or early Vedic expansions into India from the Eurasian Steppes as per Aryan invasion/migration theory. How tenable is this theory? This post does a brief analysis of the issue.

What is Kurgan Hypothesis?

The Kurgan theory got its name from the large burial mounds called tumulus or Kurgans which were common in many early bronze age Steppe cultures. The Kurgan theory states that the reconstructed extinct common ancestor of all Indo-European languages and cultures including Vedic Sanskrit and culture, called as Proto-Indo-European culture, originated in the Yamnaya culture dated to around 3500 BCE in the Pontic Steppes of southern Russia.

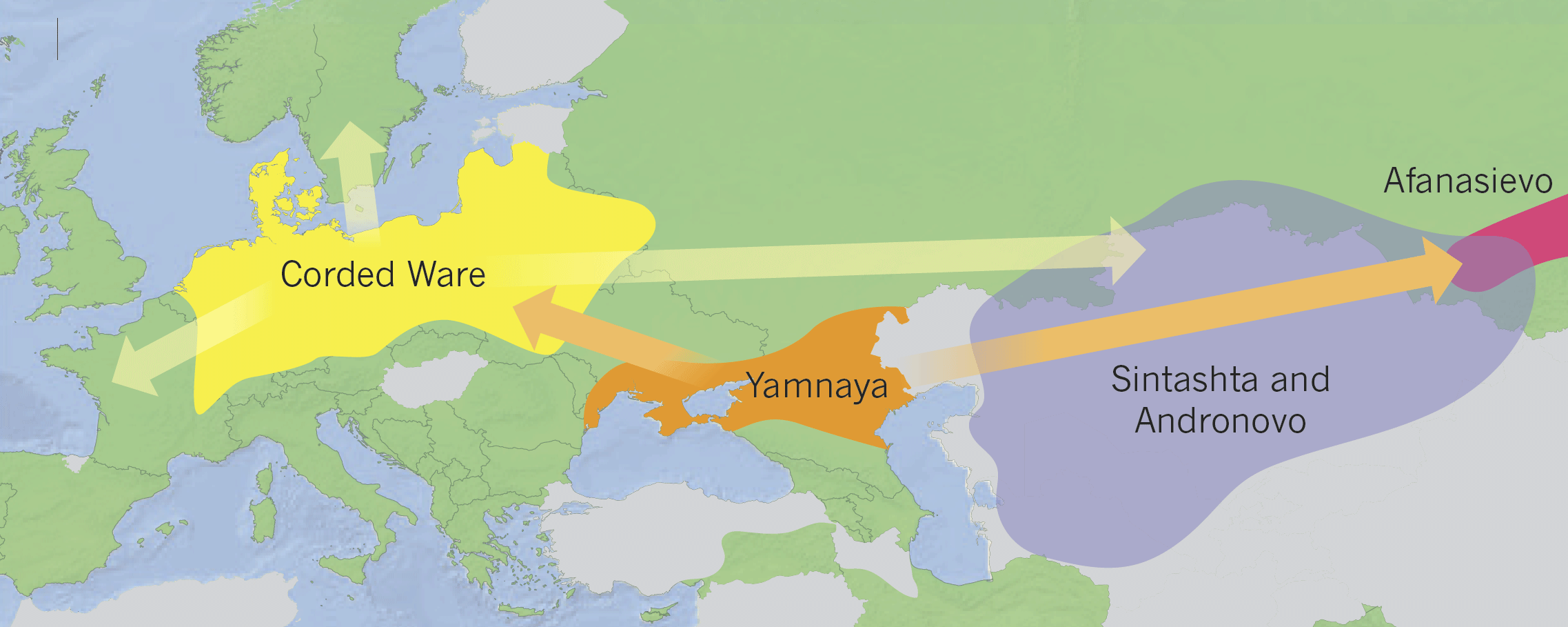

Later the Proto-Indo-European culture split off into different branches of modern Indo-Europeans. The Indo-European movement into Europe is said to have started with the Corded Ware culture and Catacomb culture dated from around 3000 BCE onwards and the movement into Asian parts started with an expansion of a culture named Afanasevo from southern Russia which reached regions as far as Mongolia during or before Yamnaya period itself. This first wave was succeeded by another wave of movement into Asia which started around 2800 BCE with the Sintashta culture and its early related cultures like Abashevo culture, Potapovka culture, Poltavka culture etc which reached regions in western Kazakhstan. Later the Sintashta culture spread into wider regions of Central Asia with its related Andronovo culture dated around 1900 BCE from western Kazakhstan. Broadly the Sintashta and Andornovo along with another culture named Srubnaya form part of same cultural zone and are classified as ancestral unified Indo-Iranian culture of both the early Vedic Indo-Aryans and the Iranians represented in the Rig Veda and ancient Iranian Avesta which split off from early Proto-Indo-European tradition of Yamnaya culture. Later, the Indo-Iranians of Sintashta-Andronovo culture took over the civilization of Bactria-Margriana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) located in Turkmenistan and northern Afghanistan by around 1800-1700 BCE and migrated further south into Iran and India after splitting off into Vedic Indo-Aryan and Iranian branches during 1700-1500 BCE. Late Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas championed this Kurgan hypothesis of Indo-European expansions.

Fig 1: Map of Kurgan hypothesis, Source : Wikimedia

So we have a wonderful adventure of the ancestors of Vedic Aryans originally from South Russian Steppes moving into Asian part of the Steppes and then into Central Asia by taking over the Bactria-Margiana culture and finally moving into India to compose Rig Veda from around 1500 BCE.

Sintashta and Andronovo chariots and horses, the cradle of Aryans?

Let us look into the identification of Sintashta-Andronovo cultures which ultimately derived from Yamnaya culture as Indo-Iranian or ancestral Vedic Aryan.

This identification of Sintashta-Andronovo cultures as belonging to ancestral Indo-Iranian culture is mainly based on the evidence of chariot usage in Rig Veda and the earliest attested chariots from around 2100 BCE in these cultures. Argument in favour of Kurgan theory is that the horse riding first occurred in the Steppes along with later invention of chariots which also happened in the Steppes at around 2100 BCE and the early Vedic texts should post-date this period since it mentions chariots and horses. Thus, the argument is that the Harappan/Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization was pre-Vedic since it did not have usage of horses or chariots.

Fig 2 : Sintashta Kurgan burial with Chariot and horses (Paprola 2005).

It is true that we don’t find any large amount of horse or chariot remains in Harappan/Sarasvati-Sindhu sites or in other parts of India like we do in Steppes. But we don’t find any large amount of horse and chariot remains in post Sarasvati-Sindhu cultures either. Chariot remains and depictions mostly only start appearing during Buddhist times, their first confirmed depictions are from Mauryan-Magadhan era dated from 400 BCE onwards.

Fig 3 : Chariot wheel from Pataliputra, Mauryan era. This is one of the earliest discovery of physical spoked wheel from India. (Gupta 1963).

Also forget chariots, even cart and wagon remains are scarce in Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. Most of the wheeled vehicles from Sarasvati-Sindhu are found only in few miniature toy models and some of the terracotta toy wheels from Sarasvati-Sindhu sites does have spoked wheel designs. Along with this, metal amulets from Balochistan dated around 4th millennium BCE also are in spoked wheel designs.

Fig 4 : Amulet in shape of spoked wheel from Mehrgarh. (Thoury et al 2016)

Also the recent finds at Sanauli site includes discovery of chariot. This is dated close to 2000 BCE, almost similar age to steppe chariots when they became widespread. Though Sanauli chariot didn’t have spoked wheels, it was certainly used for warfare as many weapons were also found. This would indicate that bronze age Indians already knew about making war chariots. The Harappan link to the site is clear as coffins from there have typical Harappan horned God motifs.There would be more such finds still yet to be unearthed.

As for horses, it is true that there are few depictions and remains of horses found in certain post Sarasvati-Sindhu cultures and sites like Gandhara grave culture in Swat valley, Pirak in Balochistan, Painted Gray Ware and Northern Black Polished Ware cultures of Gangetic plains, certain megalithic sites etc. But none of these cultures or sites are horse-centric and we have no large remains of horses or Kurgan burials with horses and chariots like in the Steppes in these cultures and sites. Horses remain rather poor in these cultures and sites compared to the situation in the steppes. It wouldn’t have been the case if the Aryans came down with their heavy horse and chariot usage into India.

There are also few horse remains reported from earlier sites which are dated to the Sarasvati-Sindhu era like Surkotada, Kuntasi, Kalibangan, Mahagara etc. But most of these findings are rejected by the mainstream authors who argue for Aryan migration by stating that these remains may belong to other equine animals similar to horses like donkeys and onagers because their remains are hard to distinguish from those of horses. While on the other hand they take the supposed horse remains from sites like Pirak and Swat valley for granted since it suits their preconceived post Sarasvati-Sindhu timeline of Aryan migration. If the Sarasvati-Sindhu era remains are of other horse like equines, then why can’t the post Sarasvati-Sindhu remains be also of so called horse-like animals as well?

Also it is indeed true that even historically Indians were importing horses (Trautmann 2007). There was even a tribe named Aśvaka in north-western India during early historic period. As their name indicates they were associated with horses and were located perhaps in modern regions of Afghanistan and Central Asia. But all this doesn’t mean that Aryans came into India and introduced horses in India. The Harappans would’ve all likely familiarized with horses via trade. If one can argue that appearance of horses is sign of Aryan arrival, there is also a space for the argument that Harappans migrated to Central Asia and West Asia because these regions had presence of Indian humped Zebu cattle in the bronze age which was domesticated originally in India (Matthews 2002). The movement of animals would not indicate mass movement of people. It can also transfer through other contacts.

Anyway, the recently rediscovered Caspian horses are native to Iran, and it has ancient presence there since the remains of the Caspian horses dated to 4th millennium BCE have been found. These horses are lighter and shorter than average horses. They were also later utilized by the Persian empires. Since Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization had good contacts with regions of Near East, it is possible that they also familiarized themselves with horses and the equine remains from Sarasvati-Sindhu sites would have included remains of lighter horses like the Caspian horses whose remains can be mistaken for other lighter equines like onagers and donkeys.

A Caspian Horse. Source

After all, even the authors who deny the presence of actual horses in Sarasvati-Sindhu sites admit that it is hard to distinguish horse remains from that of other equines. To quote Richard Meadow who wrote on Harappan horse remains:

“In sum, based on what we observed in Delhi and have outlined above, we cannot accept without serious reservations Bokonyi’s identifications of any of the Surkotada material as true horse, but in the end that may be a matter of emphasis and opinion.”

“One final point needs to be made. Even if one or even a few bones should turn out to be undoubtedly from true horse, that does not mean that every equid bone, by association, is from horse. Each specimen has to be evaluated on its own merits, and for some—perhaps even most—one can only identify the genus (Equus) but not the species (E. hemionus, E. asinus, E. caballus or hybrids) from which they came.” (Meadow and Patel, in Trautmann 2007).

Anyway as long as we don’t have large amount of horse and chariot remains along with widespread practice of erecting Kurgan burial mounds in post Sarasvati-Sindhu cultures and sites, we cannot say that the Aryans moved into northern India from Steppes during post Sarasvati-Sindhu phase with their heavy horse and chariot usage.

Did Sintashta-Andronovo had Vedic Aryan elements?

Indo-Europeanists like David W Anthony and E E Kuzmina also argue that certain details found in Vedic and Avestan texts matches the material remains of Sintashta-Andronovo cultures. Let us look into these claims.

Anthony associates the description of Aśvamedha ritual or Vedic horse sacrifice as described in Rig Veda 1.162 with the burials found in Sintashta-Andronovo culture which has yielded horse remains. To quote him:

“The horse sacrifice at a royal funeral is described in RV 1.162: “Keep the limbs undamaged and place them in the proper pattern. Cut them apart, calling out piece by piece.” The horse sacrifices in Sintashta, Potapovka, and Ftlatovka graves match this description, with the lower legs of horses carefully cut apart at the joints and placed in and over the grave. The preference for horses as sacrificial animals in Sintashta funeral rituals, a species choice setting Sintashta apart from earlier steppe cultures, was again paralleled in the RV. Another verse in the same hymn read: “Those who see that the racehorse is cooked, who say, ‘It smells good! Take it away!’ and who wait for the doling out of the flesh of the charger-let their approval encourage us.” These lines describe the public feasting that surrounded the funeral of an important person, exactly like the feasting implied by head-and-hoof deposits of horses, cattle, goats, and sheep in Sintashta graves that would have yielded hundreds or even thousands of kilos of meat.” (Anthony 2007):

But actually, the Aśvamedha ritual involves the horse being sacrificed and offered into the sacrificial fire as mentioned in Rig Veda 1.162.19, instead of being buried in the graves. The Aśvamedha ritual involves a fertility rite which is also focused on the prosperity and sovereignty of the kingdom. It has nothing to do with any graves or burials. Also, the steppe graves often contained multiple horses while only a single horse is utilized in Aśvamedha. And like mentioned before we don’t have any mass remains of horses like we see in Steppe Kurgans during post Sarasvati-Sindhu phases either if the Aryans came in during this time.So this identification of Sintashta-Andronovo as proto-Vedic based on Aśvamedha rite is absurd.

In similar lines, Anthony has also highlighted mass remains of dogs found in Srubnaya culture which was related to Sintashta-Andronovo culture and connects these remains with a group of Vedic people called Vrātyas

“In the RV the oath brotherhood of warriors that performed sacrifices at midwinter were called the Vrātyas, who also were called dog-priests. The ceremonies associated with them featured many contests, including poetry recitation and chariot races. At the Srubnaya settlement of Krasnosamarskoe (Krasno-sa-MAR-sko-yeh) in the Samara River valley, we found the remains of an LBA midwinter dog sacrifice, a remarkable parallel to the reconstructed midwinter New Year ritual, dated about 1750 BCE. The dogs were butchered only at midwinter, many of them near the winter solstice, whereas the cattle and sheep at this site were butchered throughout the year. Dogs accounted for 40% of all the animal bones from the site. At least eighteen dogs were butchered, probably more. Nerissa Russell’s studies showed that each dog head was burned and then carefully chopped into ten to twelve small, neat, almost identical segments with axe blows. The postcranial remains were not chopped into ritually standardized little pieces, and none of the cattle or sheep was butchered like this. The excavated structure at Krasnosamarskoe probably was the place where the dog remains from a midwinter sacrifice were discarded after the event. They were found in an archaeological context assigned to the early Srubnaya culture, but early Srubnaya was a direct outgrowth from Potapovka and Abashevo, the same circle as Sintashta, and nearly the same date. Krasnosamarskoe shows that midwinter dog sacrifices were practiced in the middle Volga Steppes, as in Chariot Warriors 4II the dog-priest initiation rituals described in the RY. Although such direct evidence for midwinter dog rituals has not yet been recognized in Sintashta settlements, many individuals buried in Sintashta graves wore necklaces of dog canine teeth. Nineteen dog canine pendants were found in a single collective grave with eight youths-probably of initiation age-under a Sintashta kurgan at Kammenyi Ambar 5, kurgan 4, grave 2” (Anthony 2007)

We don’t know the context of these dog remains and actually the Vrātyas became prominent from later Vedic period onwards. We don’t find any mention of ‘dog priests’ in Rig Veda at all. Vrātyas are mentioned throughout in 15th book of Atharva Veda and in later texts. In fact Pañcaviṃśa Brāhmaṇa 17.1-4 describes a ritual called Vrātyastoma to convert Vrātyas into orthodox Vedic fold. Further, later texts like Manusmriti 10.20 mentions Vrātyas as degraded people. Perhaps they were a semi-mythological heterodox group different from mainstream Vedic groups and thus cannot in anyway represent the ancestral version of Vedic culture. Moreover, just like the horse remains, we don’t have any traces of mass dog burials in post Sarasvati-Sindhu cultures. It wouldn’t have been the case if so called Vrātyas with their dog burials came down from Steppes into India and still practiced their dog sacrifices in post Sarasvati-Sindhu phases.

On the other hand late Russian archaeologist Kuzmina also claims that horses and chariots were involved in funeral rite of Vedic Kṣatriyas or the warrior caste:

“After that, according to the Śatapatha Brāhmana (12.8.1) they addressed the god Pūan, the protector of domestic cattle and roads, with these words: “Pūsan carries you to the ancestors”; they then slaughtered the sacrificial animal. A black cow was given to the brahman (priest), a goat or ram to the vaiśya (commoner), and his horse and chariot to the ksatriya (warrior); these were to help the deceased to cross the river to the kingdom of the dead.”(Kuzmina 2007)

She cites from Śatapata Brāhmaṇa for this practice but when I checked both Mādhyandina and Kāṇva versions of Śatapata Brāhmaṇa, there is no such mention of funeral rites related to horses or chariots. So this is just a desperate but yet dishonest attempt to link Steppe practice to Vedic one by citing a non-existent source.

Kuzmina had also cited Rig Veda 10.56 as reference to horse sacrifice during funeral rites in connection with steppe rites.

“It is said in the Rigveda, in the burial hymn to a horse (10.56) that carries a man’s body to heaven: “By merging with a body, grow lovely, dear to the gods in the highest birthplace. Victorious racehorse, let your body, carrying a body, bring blessings to us and safety to you.” The horse is burnt with its master. This ritual was also known among the Greeks: in the Iliad (23.175) Achilles brings horses to the funeral pyre of his friend Patroclus (Vermeule 1979). And in a Rigveda hymn (10.135.3) the dead father of the boy goes to Yama’s kingdom on “a new chariot without wheels, which had only one shaft but can travel in all directions.” (Kuzmina 2007).

But actually the hymn mentions vājin, a term which can refer to horses, but also can refer to anything which is swift, strong, vigorous, heroic etc or even a personal name. The hymn tells us nothing of any burial rite as Kuzmina thinks, but is mostly about pleasures attained in heaven. Similarly, Kuzmina also cites Rig Veda 10.135.3 as reference to funeral rite connected with chariot, again supposedly reflecting steppe chariot burials. But here the chariot is spoken as travelling in all directions without wheels and is made from mind, which could in all probability refer to some metaphysical or metaphorical chariot rather than any actual chariot. Also this hymn does not provide any information about funeral rites either.

After horses and dogs, Kuzmina have also pointed out absence of pigs from Sintashta-Andronovo culture and highlights supposed avoidance of pigs by Indo-Iranians to connect them with Sintashta-Andronovo zones

“The next step in identifying an Indo-Iranian ethnos with a concrete archaeological culture is to uncover those ethnic indicators that clearly distinguish Indo-Iranian culture from that of other Indo-Europeans. These ethnic indicators include the fact that of all the Indo-European peoples virtually only the Indo-Iranians did not raise pigs nor sacrifice them and only the Indo-Iranians raised Bactrian camels and had a cult of this animal. As far as I know the only Bronze Age culture that did not practice pig raising was the Anclronovo. As for the Timber-grave culture, pig is present in osteological materials although there is no cult of the animal. “ (Kuzmina 2007)

But on the other hand, we have usage of pigs in post Sarasvati-Sindhu iron age cultures like Painted Gray Ware. To quote veteran Indian archaeologist BB Lal

“The other animals identified at Hastinapura were sheep (ovis vignei Blyth, race domesticus), buffalo (Bos (Bubalus) bubalis Linnaeus), pig (Sus cristatus Wagner var. domesticus Rolleston), and horse (Equus caballus Linnaeus).26 A large number of bones of cattle, sheep, buffalo and pig had incision marks made with a sharp instrument, and were charred, indicating that these animals were slaughtered for food.” (Dani & Mikhaĭlovich 1992)

Obviously by the time of Painted Gray Ware in 1st millennium BCE, many parts of northern India were Aryanized even according to the Aryan migration theory. So why did the supposed steppe proto Vedic Indo-Aryan tribes who avoided pigs suddenly utilize pigs when they came into India? It doesn’t make any sense at all.

Another argument about Indo-Iranian or proto-Vedic identification of Sintashta-Andronovo cultures comes from burial of a human corpse which have its head replaced with that of a horse discovered from Potapovka culture which was related to Sintashta-Andronovo culture. Certain authors like Finnish Indologist Asko Parpola cite it as representing the Vedic myth of Sage Dadhyanc whose head was replaced with that of a horse. This myth is already mentioned in certain verses of Rig Veda like Rig Veda 1.117.22, 1.119.9 etc.

“The Dadhyanc legend also speaks of providing a human sage with a horse’s head. Such an operation may have been an integral part of the secret rite of reviving a dead hero. It is tempting to see this Aivin-related revival rite revealed in a human skeleton with the skull of a horse, which was excavated in a unique grave near Samara in the Mid-Volga region of Russia; it belongs to the Potapovka culture, dated to c. 2100-1700 nce, and was very probably the skeleton of a Proto-Indo-Aryan speaker (chapter 7) (Fig. 11.2). The secret knowledge of revival is, moreover, connected with honey, which the Vedas con-nect above all with the Aivins, the divine healers.” (Parpola 2015)

Fig 5 : Supposed human skeleton with horse head (Parpola 2015).

But in reality the myth has nothing to do with any grave or funeral. Also according to the myth, the horse head was again later replaced by the actual human head as cited in Śatapata Brāhmaṇa 14.1.1.24 . So this identification of the Potapovka remains with the Vedic myth is quite funny. Further Anthony himself states that this identification is no longer tenable.

“In Table 1, sample AA 47803, dated ca. 2900-2600 BCE, was from a human skeleton of the Poltavka period that was later cut through and decapitated by a much deeper Potapovka grave pit. A horse sacrifice above the Potapovka grave is dated by sample AA 47802 to about 1900-1800 BCE. Although they were almost a thousand years apart, they looked, on excavation, like they were deposited together, with the Potapovka horse skull lying above the shoulders of the decapitated Poltavka human. Before dates were obtained on both the horse and the skeleton this deposit was interpreted as a “centaur”—a decapitated human with his head replaced by the head of a horse, an important combination in Indo-Iranian mythology. But Nerissa Russell and Eileen Murphy found that both the horse and the human were female, and the dates show that they were buried a thousand years apart. Similarly sample AA-12569 was from an older Poltavka-period dog sacrifice found on the ancient ground surface at the edge of Potapovka grave 6 under kurgan 5 at the same cemetery. Older Poltavka sacrifices and graves were discovered under both kurgans 3 and 5 at Potapovka cemetery I. The Poltavka funeral deposits were so disturbed by the Potapovka grave diggers that they remained unrecognized until the radiocarbon dates made us take a second look. The “centaur” possibility was mentioned in Anthony and Vinogradov 1995, five or six years before the two pieces were dated. Of course, it now must be abandoned.” (Anthony 2007)

Another important argument made by Kuzmina is that certain hearths discovered from Andronovo zones resemble Vedic ritualistic fire altars.

“Andronovo houses were heated and illuminated by hearths of various types. Type 1 had an open round or oval fire-place, 0.7-3m in diameter, sometimes floored with stone. Such fires, that met both domestic and industrial needs, are found both inside and outside of houses. This type of hearth (gulkhan aloe) is known in Central Asia, first of all among the Iranian Tadzhiks and Pamiri, and is to be found in communal houses for men where it originated from early Iranian houses of fire (Pisarchik 1982: 72). Type 2 hearths comprise a shallow round or oval pit, 0.5-0.8m in diameter, sometimes more, 0.15-0.4m deep, and often covered with flat stone slabs on the bottom (Fig. 10). This is the most widespread type of hearth and served for cooking, heating and lighting; it is similar to the Central Asian type of hearth known as the chakhlak or chagdon (Pisarchik 1982: 78, 79, 109 ). This hearth is described in ancient Indian texts as the domestic fire garhapatya- `fire of the master of the house’ (Mandel’shtam 1968: 126). Such hearths were used for ritual purposes: a bride would go around it, a widow would perform a funeral dance, people jumped over it during a feast. The gulkhan (hearth) from gut- ‘heat’ is preserved in the Iranian and Indian languages (Pisarchik 1982: 74-77, 105, 106). The third type of hearth has a rectangular form, from 0.7 x 1m to 1.5 x 2m, and was made of closely adjusted rectangular stone slabs inserted into the ground on their narrow ends. Such hearths were found in the center of a house, kept clean, and it is likely that they had a ritual function (Atasu, Buguly, Shandasha, Ushkatta 11, Spasskiy Most, Kent, Tagibay-Bulak, Dongal). This type of hearth corresponded to the early Indian special cult hearth ahavaniya (Mandel’shtam 1968: 126). Rectangular and round hearths have parallels in ancient Rome where the round hearth used for cooking was dedicated to the goddess of the domestic hearth Vesta; the square hearth was dedicated to male gods and the ancestors (Dumezi I 1954).”(Kuzmina 2007)

As we can see, it is said that the hearths also contained stone slabs. While Vedic altars are usually made of bricks and has no relation with any stones or slabs. So there is no resemblance between Andronovo hearths and Vedic altars.

While mentioned Vedic fire altars, it is also good to mention about the cremation of corpses which was prevalent in later phases of Sintashta-Andronovo culture called Fedorovo culture. Since Vedic people also practiced cremation, authors who argue in favour of Vedic Aryan homeland in the Steppes identify Andronovo as representing the ancestral version of Vedic culture. But in reality, cremation was already widespread well before its attestation in Sintashta-Andronovo. The late Sarasvati-Sindhu Cemetery H culture practiced cremation and it certainly predates the later Fedorovo phase of Sintashta-Andronovo culture. Also even Anthony now admits that the cremation custom was picked up by the Andronovans from the pre-Andronovo local culture of Central Asia.

“The pre-Andronovo mortuary custom of cremation documented at Tasbas and Hegash continued into the Andronovo period as a distinctive trait of Fedorovo mortuary rituals in the Tien Shan region but with the addition of a kurgan, stone knees, and other Andronovo traits absent from the I3egash la and fasbas level I mortuary customs. At both sites. the earlier pre-Andronovo phase was followed in 1800 to 1500 BC by Andronovo styles of material culture. As the evidence now stands, it seems that the local pre-Andronovo cultures of the northern Tien Shan were absorbed into the Andronovo cultural interaction.” (Anthony 2016)

Also certain earlier Sarasvati-Sindhu sites like Tarkhanwala Dera also have evidences of cremation (Possehl 2002). It also worth mentioning that Vedic people practiced both cremation and burial as mentioned in Rig Veda 10.16, 10.18 and also in 10.15.14, but none of the Vedic texts mentions about erecting large Kurgan mounds which were filled with horse, chariot and other remains which was a common practice in bronze age steppe cultures.

Anthony also cite Rig Veda 10.18.4 which mentions about burying death beneath the mountain as evidence of erecting Kurgan.

“Similarities between the rituals excavated at Sintashta and Arkaim and those described later in the RV have solved, for many, the problem of Indo-Iranian origins.4° The parallels include a reference in RV 10.18 to a kurgan (let them … bury death in this hill”), a roofed burial chamber supported with posts (“let the Fathers hold up this pillar for you”), and with shored walls (1 shore up the earth all around you; let me not injure you as I lay down this clod of earth”). This is a precise description of Sintashta and Potapovka-Filatovka grave pits, which had wooden plank roofs supported by timber posts and plank shoring walls.” (Anthony 2007)

But the whole context of the hymn makes it clear that the verse refers to getting rid of or burying death itself, and not the corpse, by living for many autumns in a poetic sense as mentioned in Rig Veda 10.18.1-2. It’s part of the Rig Vedic poetry. So it does not talk about erecting any Kurgan over the burial of corpse. Also Rig Veda 10.18.11 of the same hymn asks the earth not to press down the corpse downward heavily and to to cover the corpse gently like a mother would cover her child. This would indicate that there were no huge Kurgan mounds were erected, but rather it was a simple burial. Further, we read from Śatapata Brāhmaṇa 13.8.1.5 that Vedic people built four cornered burials instead of round ones which was practiced by ‘easterners and others’ of ‘Asura nature’, perhaps referring to non-Vedic tribes located further east from Vedic region in northern India. This clearly indicates that the round burials, including the Kurgans, were non Vedic. Moreover we have no trace of any Kurgan mounds in post Sarasvati-Sindhu cultures, but there are few isolated findings of mounds discovered at the Sarasvati-Sindhu site of Dholavira, which is dated to the mature Sarasvati-Sindhu phase (Bisht 2015). These mounds have bases with plan of spoked wheel design which is not found in the steppe Kurgans, and reminds us of later plans of Buddhist stupas.

All these being said, there is nothing Vedic or proto Vedic in the Sintashta-Andronovo cultures. Most of the supposed parallels between Sintashta-Andornovo and Vedic practices like Aśvamedha, avoidance of pigs, association of Vrātyas with mass dog remains, burial of a man whose head replaced with that of a horse etc are untenable because they either doesn’t match the Vedic descriptions or doesn’t have parallels in post Sarasvati-Sindhu cultures, which would have not been the case if steppe people penetrated into India during this period with these cultural traits. Kuzmina also cites a lot of other supposed parallels between Vedic and Sintashta-Andronovo culture from the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, but they too hold little weight as the epics were composed much later after early Vedic literature and would only represent later or post Vedic situation.

Uralic interactions with Indo-Iranians

Yet another argument to prove that Sintashta-Andronovo culture as Indo-Iranian or proto Vedic is that Uralic languages spoken near former Sintashta-Andronovo zone contains many Indo-Iranian loan words and they inherited these words from the Indo-Iranians of Sintashta-Andronovo culture. However, if the ancestors of Vedic people really had contacts with the Uralic speakers and passed on the Indo-Iranian loanwords to the Uralic people, shouldn’t we expect few Uralic loans in Sanskrit as well? Why don’t we find any Uralic loans in Sanskrit? Linguists have found supposed loan words belonging to Dravidian or Munda or from some unknown language X in Vedic Sanskrit as already discussed above, but have find no traces of any Uralic loan in it. So this argument is quite untenable. After all, the supposed Munda or Dravidian and other loans got into Sanskrit and vice versa after the Vedic people mingled with these new groups after arriving in India. So why didn’t it happen in the case of Urlaic if the ancestors of Vedic people mingled with them near the Sintashta-Andronovo zone? In my opinion these supposed Indo-Iranian loans in Uralic could be from early contacts with steppe tribes like Scythians who were present in Uralic regions in the historical times. While we are not sure about the language of early Scythians, it is possible that certain Scythian groups may have spoken something related to Indo-Iranian and passed on these loans to the Uralics.

On the supposed Aryan or Indo-Iranian Colonization of Central Asia

Since there are no traces of any steppe cultures in post Sarasvati-Sindhu period, many authors who argue for Aryan migration states that the Bactria-Margiana culture (BMAC) of northern Afghanistan and Turkmenistan was taken over by Sintahta-Andronovo people by around 1800 BCE onwards and they adopted the material culture of Bactria-Margiana while migrating into India. Mainstream authors prefer this proxy theory because while there are no steppe elements in post Sarasvati-Sindhu phases, there are few traces of Bactria-Margiana elements showing up in certain post or late Sarasvati-Sindhu cultures like those of Pirak, Gandhara grave cultures in Swat valley, Jhukar culture in Sindh etc. But these sites also shows continuity with the earlier traditions according to the archaeologists.

Also the Bactria-Margiana elements does not penetrate much into the Sarasvati region, which was the stronghold of Vedic culture. Few immigrants from Bactria-Margiana might have come down into these neighbouring regions, but we cannot say that full-fledged Aryanization of India took place based on few Bactria-Margiana elements found in these few sites which also shows continuity from earlier traditions. Also the connections of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilizaion with Bactria-Margiana goes well beyond this post Sarasvati-Sindhu period. Many traces of Sarasvati-Sindhu seals and ivory artifacts in Bactria-Margiana culture as well (Fernez 2017) Many Bactria-Margiana seals also shows close affinities with Sarasvati-Sindhu seals and patterns. Also the Sarasvati-Sindhu site of Shortugai was established right near Bactria-Margiana zone and served as a trading outpost. So it was mostly mutual close relationship rather than any one way cultural replacement. The Bactria-Margiana elements in late Sarasvati-Sindhu phases can also be viewed as remnants of this close mutual relationship rather than any introduction of new culture and we cannot claim that a cultural replacement took place simply based on few Bactria-Margiana cultural traits here and there because numerous artifacts from Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization are discovered from Mesopotamia, but this doesn’t mean that Sarasvati-Sindhu culture made a hard impact on the culture and language of Mesopotamia.

Now some authors like Michael Witzel have even speculated about the language of Bactria-Margiana culture based on supposed non Indo-European loanwords found in Vedic and Avestan languages. But actually the Bactria-Margiana culture didn’t even possess a proper writing system and we have no clue about what language or languages did Bactria-Margiana people spoke. Anyway according to the mainstream authors who argue for Aryan migration, the Indo-Iranian steppe tribes acquired words for camel, brick, ploughshare etc from Bactria-Margiana culture when they colonized it.

Since Bactrian camel is native to Central Asia, they argue that Indo-Iranians familiarized themselves with Bactrian camel from Bactria-Margiana zones while on their way into India and Iran. But this is of course based on the notion about steppe tribes using Bactria-Margiana culture as a proxy for their migrations into India. If we view that the Vedic people were already present in Sarasvati-Sindhu regions, they would have familiarized with camels due to their contacts with Bactria-Margiana culture which is already pointed out. The early Avestans being closely related to Vedic people must have also been near vicinity of these regions and they too would have familiarized with it. No need to view that the Indo-Iranians got it after got it after colonizing Bactria-Margiana from the Steppes. Also Bactria-Margiana culture was an urban culture with agriculture and if Indo-Iranians colonized Bactria-Margiana zones then they would have obviously been familiarized with the urban elements. But still the mainstream theory views Vedic Indo-Aryans who split from Indo-Iranians who colonized Bactria-Margiana as pastoral nomads when they migrated into India! This pastoral-nomadic image of Vedic Aryans is one of the main reason why Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization is viewed as non-Vedic by mainstream authors. So if we accept that Indo-Iranians picked up material culture of Bactria-Margiana and adopted the urban elements of BMAC, then it would seriously contradict the pastoral-nomadic image of Vedic Aryans who migrated into India, which is the basic premise of mainstream Aryan migration theory. So from this and all other points mentioned above, the Bactria-Margiana proxy theory for Aryan migration is basically unreliable.

A Comment on Recent Genetic Findings and Aryans

If we look genetically, it is indeed true that we find paternal Y-DNA Haplogroup R1a in many parts of the Steppes and related bronze age Eastern European cultures, especially Corded Ware culture, Sintashta-Andronovo culture, Srubnaya culture, Tarim mummies etc.. This same Haplogroup is also found among many modern Northern Indians. But as I pointed out in an earlier article, we don’t have any widespread presence of R1a even during early iron age Gandhara Grave culture of Swat valley which is supposedly identified as belonging to early Vedic migrants from further north into northern parts of India. Because of this the study had to conclude that the steppe admixture is based on female line. Even this admixture is only around 20% at max, and hence not sufficient enough to change the cultural zone of entire northern India. Also another thing is that recent study states BMAC ancestry did not contribute to the Indian ancestry. Hence the BMAC proxy theory falls apart genetically as well. Finally I feel we must wait for more genetic studies on ancient DNA from within India, especially Sarasvati-Sindhu and Gangetic regions, to come to a conclusion regarding the genetic data. If there are no R1a in Harappan remains, we have no other option but to conclude that it became prevalent only after bronze age, as R1a along with low steppe admixture (max 20% as mentioned earlier) is really scarce even in iron age Gandhara Graves of Swat valley, which Indo-Europeanists associates with the incoming Vedic Indo-Aryans.

Conclusion

Thus, while the mainstream Kurgan theory could explain initial Indo-European expansions into Europe from the Yamnaya culture through later cultures like corded ware and catacomb cultures, it fails to bring Indo-Iranians into India and Iran from Steppes with the speculative identification of Sintashta-Andronovo culture as Indo-Iranian and even more speculative proxy migration theory through Bactria-Margiana culture. Steppe tribes like Scythians carried on the typical bronze age steppe practices like erecting kurgan mounds, chariot and horse burials, mass graves etc into the early historic period. While the Scythians are said to be Iranic, they are distinguished from earliest attested Avestan Iranians. It is likely that the Steppe cultures were ancestral to iron age steppe tribes like that of Scythians and not Avestan or Vedic Aryans.

Bibliography

A Bronze Age Landscape in the Russian Steppes: The Samara Valley Project (2016)by David W Anthony

A Comment on “Horse Remains from Surkotada” by Sándor Bökönyi by Richard H Meadow and Ajita k Patel in The Aryan Debate (2007) by Thomas R Trautmann

A note on chariot burials found at Sinauli district Baghpat UP (@018) by Vijay Kumar

Excavations at Dholavifra 1989-2005 (2015) by RS Bisht

High spatial dynamics-photoluminescence imaging reveals the metallurgy of the earliest lost-wax cast object (2016) by M Thoury. et al

Manufacturing and trade of Asian elephant ivory in Bronze Age Middle Asia. Evidence from Gonur Depe (Margiana, Turkmenistan) (2017) by Dennys Frenez

Patna museum catalogue of antiquities (1963) by P L Gupta

The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia’ by Narasimhan et al

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language : How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World (2007) by David W Anthony

The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective (2002) by Gregory L Possehl

The origin of the Indo-Iranians (2007) by E E Kuzmina, edited by J P Mallory

The Painted Grey Ware Culture of the Iron age by B B Lal in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 1 (1992) by A H Dani and V M Masson

The Roots of Hinduism : The Early Aryans and The Indus Civilization (2015) by Asko Parpola

Zebu: harbingers of doom in Bronze Age western Asia? (2002) by Roger Matthews

Featured Image: Indo-European

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.