A Week with the Purusharthas

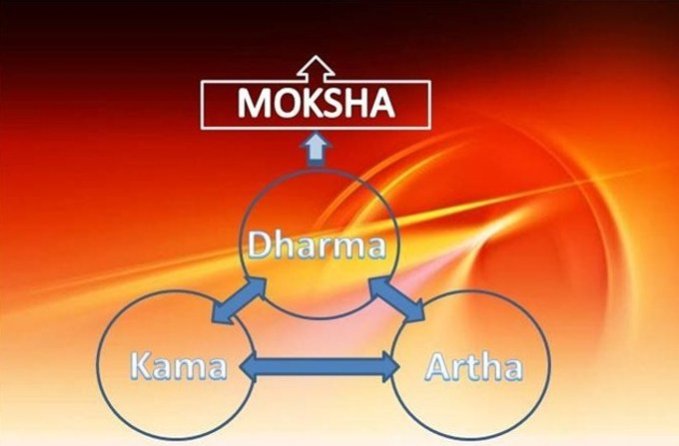

The Purusharthas, namely dharma, artha, kama and moksha, have been a central aspect of the Dharmic worldview, guiding the everyday life of millions and ensuring a balanced and harmonious fulfillment of all human pursuits. The Purusharthas give us sight of what to live for. Taken together, they give a clear vision of the sacred unity of all endeavors, elevating our pursuits from mere survival to a means of self-refinement. The Purusharthas were considered so important that texts would begin by stating which of the purusharthas they aim to fulfill. For example, Ramayana says “kamartha-guna-samyuktam dharmarthaguna-vistaram” meaning “it deals with the worth of kama and artha and treats in extension of dharma and moksa.”

In recent decades, maybe even centuries, the harmonious balance of purusharthas seems to be muddled in certain sections of India. Take for instance kama – there is a schizophrenic approach of either puritanical horror or the recent idea of kama as celebration of pure licentiousness. Similarly, artha comes under much flak by narrowing its focus to mean only money and considering it to be the source of evil and decadence.

To clear the mists surrounding the Dharmic vision of purusharthas and gain a personal understanding it becomes invaluable to study what shastras have to say, in the manner that they are meant to be studied. But there is much hesitation and difficulty because the Shastras are either maligned or revered but not usually read.

In this context, the week-long workshop titled Purusharthas: Unity or Dissonance by Dr Bharat Gupt came as a breath of fresh air. For seven days, amidst the stunning hills in the tastefully maintained Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Ramgarh, participants got the opportunity to immerse ourselves in the key shastras for Dharma, Artha and Kama. The texts chosen were the much reviled Manusmriti for Dharmashastra, the much eroticized Kamasutra of Vatsyayana for Kamashastra and the Arthashastra of Kautilya. The focus was to critically study them for what they are, on their own terms.

Learning from a Master

The extraordinary panditya (scholarship) of Dr Bharat Gupt with his mastery of Natyashastra, Greek theater and Indian knowledge traditions was matched only by his warmth and sincerity in teaching. This made the workshop a seeker’s delight. With the authority of a scholar and the flair of an artist, Bharat Gupt ji brought the world of Classical India alive before our eyes and helped us see the worldview and value systems underpinning the same. This rendition, masterful in itself, was enhanced by cross-civilizational comparisons and the endeavor to give a fresh perspective about contemporary India.

The daily schedule had an ideal mix of rigorous sessions and sufficient space for reflection. The classes by Dr. Bharat Gupt would be from 9 to 12.30 in the morning and from 4 to 6 in the evening. The rest of the day was yours to spend. For many, a typical day would begin with an early morning trek amidst the breathtakingly beautiful hills, followed by a hearty breakfast and a rich morning session. Post lunch, it was time for an afternoon siesta, followed by reading, contemplation or animated conversations over a mug of steaming chai. The evening sessions would be followed by dinner, bonfires on some nights and small discussion groups on others.

What is a Shastra?

The first session began by setting a context of what is a Shastra and how is it to be studied.

Dr Gupt gave the definition of Shastra as: Shastram iti shasanopayam – a Shastra is an instrument to create order within an area of human concern. A Shastra defines what success is, how to measure the same and how one can succeed that field. Every Shastra is written with a prayojana (purpose) in mind, for a kala or vidhya. It investigates a continuous process of achievement in its chosen field. They are written for the practitioner with the purpose of making prayoga (practice) reliable. Shastras usually do not prescribe things; in most cases they are descriptive. They don’t stand for all ages. They need to be adapted and rewritten.

A text is not to be pillaged by barging in and taking some ideas. They must be read on their own terms. Abhinavagupta says that study of a Shastra has to be done by identifying the correct reading, reconciling apparent contradictions, understanding the ideal vision the Shastra describes, studying the contemporary practice etc.

Interplay of Shastra and Lived Experience

In every Shastra, there is scope for change with time. For example Manusmriti speaks of practices that were acceptable once but no longer acceptable e.g., Niyog. Further, shastras change with place and people. Manu for instance recognizes different behaviors in different places and among different groups. He does not prescribe full uniformity. There is a clear plurality of vision underlying the shastras. The media of Natya (theatre and dance) and the continuous re-narration of the ithihasa purnanas ensured that the shastric vision spread among the whole of Bharata. Lokachara, local practice, was recognized by shastras. There was a mutual influence between shastras and lokachara with shastras influencing everyday lives of people and people impacting the shastras by lived experience.

The Dharmashastra of Manu

Manusmriti has been a seminal text in ancient India and has influenced the whole of Southeast Asia. Manusmriti vision is acharasya pradhanyam– a cosmic order where each being has its particular conduct in maintaining stability. This achara or conduct differs according to person, context, place and time. A fascinating thing about Manusmriti is that it never admits the possibility of a complete breakdown of dharma. Even in times of crisis, a looser apat dharma exists. There is no space for a Hobbesian chaos, a war of all against all.

Varna and Ashrama

The social vision of Manusmriti is based on Varnasharama dharma, the order of the four Varnas– Brahmana, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra and the four Ashramas – Brahmacharya, Grihasta, Vanaprashtha and Sanyasa. It was a dynamic system with mobility of jatis along the varnas. Among the four ashramas, it is only the Grihasta who was a productive member of society on whom the other three depended. The Brahmacharya, Vanaprastha and Sanyasa were non-earning phases where one pursued some form of knowledge or meaning. The Vanaprasthin and Sanyasin contributed in terms of teaching and guidance. Dr Bharat Gupt contrasted this with the modern social order where a student has to take a student loan and the elderly must depend on the state for sustenance. Varnashrama Dharma according to Dr Gupt, was accepted by the Buddhists and Jains as well. The differences between schools were at a philosophical level, but every day achara was guided by Varnasharama Dharma.

Ritual, the Arts and Transformation of Consciousness

A key aspect that the Manusmriti deals with is samskaras, rituals to recognize and enable key transition from one stage to another in life. Dr Bharat Gupt made a scathing critique of those who denigrated rituals explaining how nearly every ancient society honored them. The Indian ritual is based on the Vedic yagna which demands full involvement at the levels of Manasa (mind), Vacha (speech), and Karmana (body) to bring about a shift in consciousness. The mind would contemplate on the devata, the mouth would utter corresponding mantras and there would be simultaneous performance actions. The Vedic vision is Isha Vasyam Idam Sarvam, of the Divine inherent in every particle of the cosmos. There is no unbridgeable gap between creation and creator, sacred and profane. There is only a difference in degree of consciousness. This is why Tulsidas, who was both an Advaitin and Rama Bhakta, clearly says Rama is simultaneously agun, nirgun and sagun. It is this vision of yagna, of aligning thought, word and action to bring about a transformation that gave rise to the extraordinary performing arts of India. Without sagunopasana, Dr Bharat Gupt says, there would be no kala in India. Every art form was upasana, a sadhana of rasa, to bring about a shift in consciousness of the performer and listener and manifest Divinity on the sacred stage.

Manusmriti did not see Varnasharama Dharma as an end in itself. The purpose was to enable the purusharthas of Dharma, Artha and Kama, with moksha being implicit. The social order had no notion of rights. It was instead animated by the idea of adhikara, based on swadharma and what one contributed to society.

Different Worlds, Different Sensibilities

It is important to understand how much our worldview is shaped by the Industrial Revolution. Pre-industrial societies had entirely different mechanisms of administration, distribution of wealth and consumption. They were based on a different set of aims in life. A quick glimpse of this contrast is seen when we glance at the values embedded in our constitution- freedom, liberty, equality, fraternity etc. There is no equivalent of the purusharthic vision. Ancient India was a non-consumptive society based on the notions of responsibility and sharing.

A societal vision must be understood in its own terms without imposing our modern sensibilities upon it. It must be seen as a self-contained system. When we do this with sincerity, without being a modernist or a hagiographer of classical India, we gain access to a different vision and way of life, an alternative understanding. This allows us to step outside our everyday ‘common-sense’ and see our values and ways of life from a completely different perspective. Our understanding and living will become richer from this depth of perception and the resultant synthesis.

The Kamasutra of Vatsyayana

The second part of the workshop focused on Kama. Kama was not seen as a solitary pursuit in itself but a part of a totality. Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra begins with the benediction dharmarthakamebhyo namaha- I bow down to the purusharthas dharma, artha and kama (in that order). Vatsyayana defines kama as a pravritti– an outgoing of the five senses, the mind, the instruments of action (karmendriyas) and active enjoyment through these. Neither mere sensory titillation nor pure Platonic love qualify as Kama by this definition. Dr Bharat Gupt clearly explained how kama had a beautiful place in the Indian tradition. It was seen as natural, social and desirable. The Kamasutra commentary Jayamangala marshals arguments from the Vedas to justify how the pursuit of Kama is in line with the Vedic vision.

There is a clear justification of why humans need kamashastra. The commentator argues that humans, unlike animals, have social structures, mental complexes and psychological backgrounds. Further, humans have been ruined by excessive desire like Keechaka in the Mahabharata. Therefore there is a need for kamashastra. The author clearly recommends that kamashastra should be taught to both men and women.

Kamasutra primarily deals with the life of a Nagarika, a citizen of taste, of arts, who knows how to conduct himself/herself. The Nagarika resides in a Nagara or polis, where a cultured life is considered possible. The themes in the Kamasutra include who is a nagarika, who would help the lover approach his/her love, how to find a suitable girl to marry, how are men and women to behave with each other, how to get introductions to suitable men/women, how to approach married men/women, the life of a courtesan and the famous sections on postures and aphrodisiacs.

Life at the Courtesan House

Shocking to our current sensibilities is the idea that matrimony and sexuality are not coterminous.Veshmagrihas or courtesan houses were a key and respectable part of urban life. There were different classes of courtesans, with many among them being extremely cultured and educated in literature, poetry, music and the performing arts. The Veshmagrihas were seen as centers of culture and taste and courtesans became the muse of many a nagarika. The institution was formally recognized by the state and had a dedicated minister to oversee their functioning. The state collected taxes and took responsibility for providing healthcare to courtesans. The courtesan-house as an institution is hard for the modern sensibility to digest; we tend to equate it with modern forms of prostitution and its assorted evils of kidnappings, extortion, non-legal recognition, poverty etc. The courtesans that Vatsyayana describes are sophisticated, wealthy, independent women who are highly skilled in music, poetry, the performing arts etc. They were the inspiration of poets and their homes were abodes of discussion on literature and culture. They enjoyed both legal and social recognition. This is moral and social universe quite different from that of today.

How is a nagarika to live?

To live the life of a nagarika, one must have sufficient financial means, either through business or inheritance, and independence to spend money to one’s taste. Clearly the majority of the Nagariks spoken of seem to be Vaishyas. An ideal Nagarika home must have an open courtyard, an outer hall and inner hall. Vatsyayana says that the outer hall can have large perfumed beds with pillows at the head and feet, covered in white sheets with mosquito nets. Nearby can be a side table with exquisite perfumes, ivory tusks on the wall on which harps are hung, easels for painting, a bookshelf, garlands, a chess board, birds and garden swings. Every day the Nagarik would get his body massaged and perfumed. The afternoon was for play while late afternoons are to be spent with friends. Evenings called for musical, literary or poetic gatherings, or theatre performances. Post that, the nagarik is to perfume himself and wait for his lover or better, go visit her. The nagarik was expected to sponsor melas (city level festivals) and patronize music, theatre and the performing arts.

The Arthashastra of Kautilya

The nuanced discussions on Dharma and Kama left us with only a day for Artha. Dr Bharat Gupt characterized the Arthashastra as dealing with more than just management of wealth. It is a treatise on Political Economy, with a focus on various systems in the polity. It deals with systems of wealth generation, information, law enforcement, taxation, ethical systems that held society together etc. Interestingly, both Manusmriti and Arthashastra do not speak of a uniform social, legal or taxation code for all classes. These were customized for each class based on the social function they served. For example, the tax slabs on the Vaishyas was the highest, whereas transgenders, artisans and scholars of the Veda were tax-exempt. The king was neither the law giver nor the dispenser of justice. There were specialized classes who performed both these functions. With this discussion on Artha, the workshop came to an end.

After writing this, my mind goes back to what Dr Bharat Gupt said the first day. The Natyashastra considers siddhi or perfection to be of two types Daivi and Manushi, divine and human. It is easy to judge if humans are pleased, but how do we know if the gods are delighted? Bharatamuni says that right after a performance, if the audience is in awe, when the impact goes to the deepest core of one’s being, then the Gods are pleased. That perfectly captures our experience at the end of the seven day tour-de-force by Dr. Bharat Gupt. Surely, the gods would be pleased.

With gratitude to our course Acharya Dr Bharat Gupt and the guru paramparas of Bharat, who have passed the flame of knowledge and lived experience from master to pupil for millennia. May gurus continue to guide us.

Featured Image: Awakening Hindus