Dear Vinod Mehta: Indians threw the Nehruvian India in the bin in May 2014

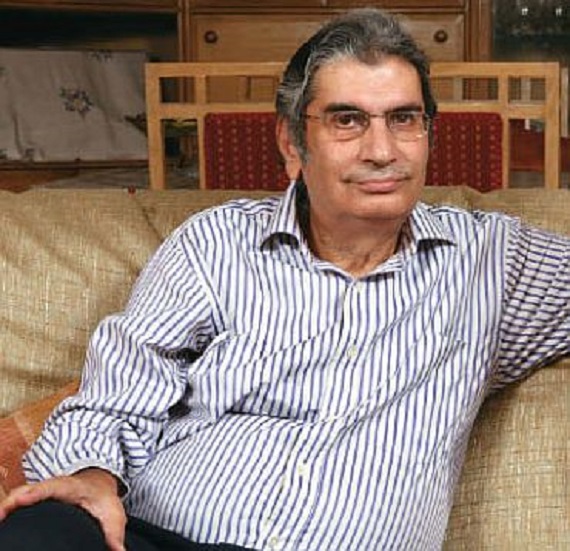

Vinod Mehta penned an article for the Times Of India blog titled ‘India’s father and daughter: Nehru and Indira laid down principles of secularism and nationalism that today’s politicians can’t ignore’ today where Mr. Mehta bemoans the recurring phenomenon of myth-busting about the contributions of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty in building post-independent India. He claims:

Consequently, 2014 onwards provides an excellent window to demolish once and for all the myth about their contribution to nation-building. What they built, so the argument goes, is their family dynasty.

Party politics can and is used to float falsehoods with the help of state power. Witness how the fable concerning our glorious Vedic past is being represented triumphantly (in which allegedly plastic surgery and stem cell research flourished) without a murmur of incredulity, or a titter of mirth. If truth is the first casualty in war, it is the second casualty in times when, as Lawrence Durrell puts it, “truth is what contradicts itself”.

The systematic and organised campaign to vilify the Nehru legacy and replace it with the more ‘muscular and patriotic’ legacy of Sardar Patel is top of the agenda. The exercise is ludicrous and an insult to the great Sardar. But let us leave that falsehood alone for the moment.

At the heart of the demolition project is the announcement that a new Idea of India, contrary to the one proposed by Nehru, is available, and in need of urgent execution.

First, I would beseech Mr. Mehta to go through this scholarly article, an extract of which is provided:

The mythological extravaganza and the poetic hyperbole of ancient Indian epics with their astounding weapons and intelligent apes and flying machines can definitely help an eager mind to break free and imagine widely. Hindu mythology can be a fertile teaching aid to make young minds get acquainted with every wild idea that comes up in science: parallel universes to time travel to extraterrestrial life……The vexed question of flying objects in the Ramayana can be used to highlight the imaginative genius of Valmiki who visualized graphically how the Indian land mass would look when viewed from a high altitude in a moving contraption…..The ways of using Indian mythology creatively in the science curriculum are many, if care is taken not to fall into the trap of a literal interpretation that breeds fundamentalism and not imagination.

If for once the liberal elites like Vinod Mehta get over their inability to comprehend India’s priceless Hindu heritage they may also see the facts for what they are and not apply flippant labels like ‘fable concerning our glorious Vedic past.’

Now Mr. Mehta, why is it ludicrous and insulting to valorise the legacy of Sardar Patel, the true architect of Post-Independent India, the man who politically unified the 500-odd princely states?

And is it not an insult that while your non-muscular hero, Pandit Nehru awarded himself the Bharat Ratna in 1955, Sardar Patel had to wait till 1991? After all, Nehru and Patel were co-freedom fighters, and worked quite closely with each other for several decades. Why didn’t your hero, Mr. Nehru, have the magnanimity to award the Bharat Ratna to Patel when the latter died in 1950?

Also, speaking of vilifying legacies, let’s take a look at this statement of India’s first President Rajendra Prasad written on 13 May 1959:

That there is today an India to think and talk about is very largely due to Sardar Patel’s statesmanship and firm administration which not only abolished all the States with the consent of the Rulers but also evoked patriotic sentiments in them to such an extent that they were grateful to him for all that he had done..

No attempt has been made in Delhi to erect a memorial. Even the portrait in the Parliament House is the gift of a ruling Prince (Gwalior). Let us not, therefore, run away with the thought that his services are any the less valuable because we choose not to recognise them.

Also pertinent is this statement from KM Munshi’s book, “Pilgrimage to Freedom”:

When I was back in Delhi (after successful integration of Hyderabad) Sardar insisted that I should call on Jawaharlal Nehru as a matter of courtesy. When I went to the Prime Minister’s office in Parliament House, he came out in the ante-room and frigidly accosted me: “Hello Munshi”. “I have come to call on you, now that I am back in Delhi,” I said. He almost turned as if to go; then he turned round, shook hands with me and left.

I told Sardar how sorry I was to have accepted his advice to see Jawaharlal Nehru. Sardar laughed and said: “Some of them are angry that you helped in liquidating the Ittehad power. Some others are angry that you did not allow them to remove the Nizam from Hyderabad straightway. Some cannot vent their anger on me, and therefore make you the target.”

Many a historian has tried to eclipse the legacy of Sardar Patel with this larger-than-life image of Pandit Nehru. Indeed if one reads the likes of Ramachandra Guha, Nehru appears as India’s greatest leader since the dawn of mankind, who possessed some minor defects.

This extract from R Jaganathan’s insightful piece summarizes the reason for this ‘ludicrous exercise’:

This extract from R Jaganathan’s insightful piece summarizes the reason for this ‘ludicrous exercise’:

The question to ask is why has Patel, till recently a near-pariah with the Marxists and unmentionable in the Congress for allegedly being a less-than-secular leader, become so important to Guha and the secularists now? The answer is, of course, Narendra Modi’s decision to appropriate his legacy. Modi actually did not do anything unique. The Sangh had always thought more highly of Patel than Nehru, but after Modi elevated the game, it became important to restore Patel’s place in the Congress hierarchy. The fact that Patel, after Gandhi’s assassination, briefly banned the RSS came in handy to enable this re-embracing of the Sardar.

Even though it is fair to say that Patel and Nehru were in the same party and, hence, comrades in a general sense, this was largely because Gandhi ensured Nehru’s pole position, and Patel acquiesced. ….Given his wide reading and international exposure, Nehru was certainly good at looking at the big global picture, but he drew woolly conclusions about India’s place in it. Patel, despite his lack of global exposure, had an instinctive feel for realpolitik and power. His hand at the steering would have made India a global power by now. But that was not to be.

In contrast, Nehru was wrong in almost all his decisions – whether it was the creation of a socialist state, his policies on Tibet and Kashmir, or tolerance for minority communalism. Patel was the guy who had a better grip on India. Nehru was the guy who failed to solve almost anything he touched, and left us a legacy of exacerbated crisis.

Further in the article Mr. Mehta states:

If one takes the short view of history, Nehru is an easy target, and Indira even easier. …..Perhaps this is the right time to ask the hunters looking for two prized scalps some questions. Where did Narayana Murthy and the entire information technology industry come from? Where did Indra Nooyi come from? Where did Warren Buffett’s financial wizard, Ajit Jain, come from? They all came from the IITs, IIMs and other world-class education centres Nehru had the foresight to set up.

If India has the ‘bomb’ and internationally renowned research labs, the credit must go to the same man. At a time when the republic struggled, he insisted a newly independent, backward nation be fully engaged with the contemporary first world through advanced learning and progressive thinking. Nehru ensured a society steeped in superstition, ritual, religious dogma and belief in kismet embraced a scientific temper so that the temptation to wallow in a mythical ‘glorious’ past could be resisted. The modern nation state – outward-looking, open, rational, argumentative, sceptical – armed with universal adult franchise, is the creation of Jawaharlal Nehru. Rubbish that if you like.

Now, now, Mr. Mehta please get your history right. The following is based on the information provided by the IIT Kharagpur website and this article from the Hindu:

In the summer of 1943, the Secretary of State for India had, at the request of the Viceroy, written to the President of the Royal Society asking “whether it is possible for them to spare Professor A.V. Hill” to advise on the organisation of scientific research. Prof Hill arrived in India on November 16, 1943 and visited Aligarh, Bangalore, Bombay, Calcutta, Kanpur, Delhi, Hyderabad, Jamshedpur, Kirkee, Madras, Mysore and Poona, and left on April 5, 1944. He submitted a 40-page report on August 14, 1944.

On page 20 of the report, he says “…there is no institution as yet in the United Kingdom comparable in magnitude, in the quality of equipment and in excellence of teaching and research work, with Massachusetts Institute of Technology at Cambridge, Mass, USA…” Later in the same page, he states that “the future of Indian industrial and agricultural development must depend upon the supply of first-class technical brains, trained in an atmosphere both of original research and of practical experience. …one or two technical institutes of the highest possible standing should be founded or developed from the existing ones (e.g., at Bangalore, where the Indian Institute of Science comes most closely of existing institutions to what is wanted)…

In 1946 a committee was set up by Hon’ble Sir Jogendra Singh, Member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, Department of Education, Health and Agriculture to consider the setting up of Higher Technical Institutions for post war industrial development in India. This committee also took the suggestions of Sir Ardeshir Dalal , Member-in-Charge of Planning and Development. The twenty two member committee headed by Nalini Ranjan Sarkar, in its report, recommended the establishment of four Higher Technical Institutions in the Eastern, Western, Northern and Southern regions.

And so it basically was a readymade report to which Nehru just had to say ‘yes’ that led to the creation of IITs. Besides, any Prime Minister in Nehru’s place would have definitely put education as a priority.

And then, Nehru’s ‘idea of India’ which Mr. Mehta describes as ‘outward-looking, open, rational, argumentative, sceptical’ was not exactly the product of an enlightened mind. This belief is debunked in this article by Swapan Dasgupta:

That Nehru was intellectually superior and didn’t tolerate fools easily are attributes that have been diligently recorded. Less publicised was the strong impression that his enlightenment was often offset by blind hates. Among Nehru’s ‘prejudices’ were ”maharajas, Portugal, moneylenders, certain American ways, Hinduism, the whites in Africa…” The list explains why Nehru was so offensive at the opening of the Ramakrishna Mission Institute in Calcutta, 1961.

There he spoke of ”bogus spirituality”, the absurdity of ”running away from the daily problems of life in the spirituality” — the profundities of undergrad radicalism — and then stalked off. ….Nehru, it was said, ”could be emphatic on a basis of insufficient knowledge”. He may have begun with a caricatured hatred of moneylenders but it soon extended into distaste for the entire private sector.

Like the fellow travellers of Stalin, he juxtaposed science with what he considered religious mumbo-jumbo and came to view everything Hindu with utmost wariness…..he probably believed that the India of ”cow worshippers and devotees of Ayurvedic medicine and astrology” should be banished from public life……From such parodies were the three pillars of the Nehruvian order, secularism, non-alignment and socialism, crafted. For a man who left the country ”not better fed, clothed or housed, …more corruptly governed…with higher taxes, ever-rising prices, ever-acute foreign exchange difficulties, and more unemployment” than when he took charge, India has been too kind to Nehru.

An interesting point to note here is that the model of the IIT was based on Bangalore’s Indian Institute of Science, which was established way before India’s independence by the Tatas. Mr. Mehta, please do read the following:

I trust, you remember me as a fellow-traveller on your voyage from Japan to Chicago. I very much recall at this moment your views on the growth of the ascetic spirit in India… I recall these ideas in connection with my scheme of Research Institute of Science for India, of which you have doubtless heard or read.

This letter was written by Jamsetji N. Tata to Swami Vivekananda five years after their meeting on a ship in 1893 where Tata was inspired by Vivekananda’s views on science and leadership abilities, an inspiration which led to the founding of IISc.

Thus in a way, the origin of IIT lies actually in a conversation between a greedy businessman and a bogus spiritualist, both objects of extreme Nehruvian hatred.

And unlike the IIT, the IISc was the only Indian university ranked in the top 500 by the Academic Ranking of World Universities, at 301-400th place overall in 2011 and managed to maintain its overall ranking through the 2012 and 2013 rankings.

Also, Mr. Mehta, the credit for the ‘modern nation state – outward-looking, open, rational, argumentative, sceptical’ should be given to our ancient sages who never made dogmatic declarations on issues of science and in their works, offered diverse viewpoints in topics like human existence, composition of the universe and elements of nature:

Fortunately, India has always nurtured a culture of philosophical pluralism which also means the existence of both epistemological and ontological pluralism. The organic relation between epistemology and good science cannot be overstated. In the words of Einstein:

The reciprocal relationship of epistemology and science is of a noteworthy kind. They are dependent upon each other. Epistemology without contact with science becomes an empty scheme. Science without epistemology is – insofaras it is thinkable at all – primitive and muddled.

The six darshanas that Hindu culture has nurtured, differ with one another. There are theistic and atheistic systems built over them. For a non-Indian observer, these systems may look mutually incompatible. Yet they have coexisted and cross-fertilized each other. Every student of philosophy, religion, astronomy, medicine and mathematics imbibed the texts of all the six darshanas so they never had an ideological or theological anxiety about the implications of scientific exploration in India.

Many personalities in India actually attempted, in the words of famed physicist Satyendranath Bose, ‘the unprecedented synthesis of scientific temper and spirituality.’ Notable among them were Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937) and Prafulla Chandra Ray (1861-1944). Unlike Nehru, both Jagadish Chandra Bose and Prafulla Chandra Ray did not deride Indian traditions, and were among the first to demonstrate how ancient Indian thought systems are compatible with modern notions.

Yet why don’t we hear much about them? Indeed, many educated under the Nehruvian scheme of “education,” don’t even know these scientists existed. The answer is given by Ashok Malik:

Yet why don’t we hear much about them? Indeed, many educated under the Nehruvian scheme of “education,” don’t even know these scientists existed. The answer is given by Ashok Malik:

Post-independence, the Congress establishment sought to rewrite history in its own image. It determinedly underplayed the role of the early Indian elites — the Poona Brahmins, Bombay’s Parsi constitutionalists, Calcutta’s Bengali and Brahmo activists — who had dominated public life prior to the Mahatma’s mass politics.

As the Congress set out to establish that there was no history and no freedom struggle before Gandhi, and no politics and no consciousness of modern India before Nehru, these pioneer groups became expendable. The Marxist historians who actually wrote the textbooks had their own theories.

Vinod Mehta concludes his article with the following claim:

If Nehru’s legacy is the real obstacle holding India back, why don’t its adversaries throw it into the wastepaper basket? And govern on the majoritarian doctrine? Not a chance. When it comes to self-preservation, the new rulers are wise. They know they would soon be out of a job, if they abandoned the idea (secularism) which has held the country together.

Mr. Mehta if anyone rubbished Nehru’s legacy it was his own family and party:

1. In your own words, Indira Gandhi robustly encouraged the army to retaliate against Pakistan’s attacks in contrast to her naively pacifist father’s act during the 1962 Sino-Indian war. It was also Indira Gandhi who treadled democracy when she saw it fit.

2. It was the same Congress party which in 1991 decided to throw Nehruvian socialism in the furnace of history and embark on economic reforms. Indeed, if it had the same conviction in Nehruvian socialism that held it in power for so long, why did it discard it?

3. Finally, it is Nehru’s great grandson who by complimenting Gujarat’s women for giving excess milk, empowering Venezuelan women, asking Dalits to attain the velocity of Jupiter and other absurdities, did his best to put the Nehru clan in such a horrible light that the combined power of Vinod Mehta’s pet hate, the Sangh Parivar’s combined strength couldn’t manage to do. Indeed, it was Rahul Gadhi’s serial absurdities that handed the Congress its worst ever defeat.

And lastly, India’s “hearty secularism” is a continuation of the traditions set by a 5,000-year old civilizational genius that did not give a monopoly to any single god, and gave every individual a right to choose his path to god. Pandit Nehru was the recipient and not the creator of this ethos, which his devotees have undermined for decades and have created the mess India is now in.

Unlike the Nehruvians, the votaries of the so-called majoritarian doctrine actually take scholarly sustenance from the Indian ethos, so rest assured that the nation is in the right hands. And Mr. Mehta, please do realize that it is the generation of argumentative and skeptical Indians who are debunking the myths of Pandit Nehru unlike what your kind did to the present PM.