Decoding the Aam Aadmi Party

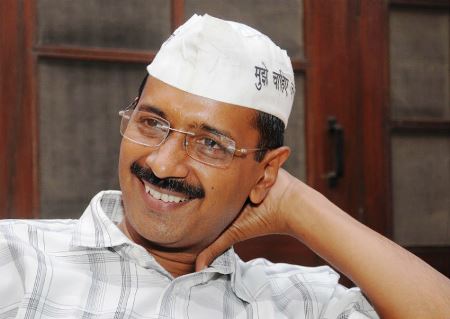

By any reckoning, Arvind Kejriwal’s rise is astounding. One year in politics, and he is chief minister of the Delhi state. As I mentioned in an earlier article, he has blasted many a myth about Indian politics and political action. Many liberals and secularists must be pinning their hopes on Kejriwal and his Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) to jeopardize, if not check the Narendra Modi juggernaut. But can Kejriwal be a threat to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)? There are no ready answers; a lot will depend upon the BJP’s response to the AAP phenomenon. Till very recently, the saffron party, like many an analyst, had failed to understand the AAP which has the potential to upset the applecart.

On the face of it, there is nothing spectacular or profound about the party. The AAP’s Vision document and election manifesto are hodgepodges of wishful thinking, platitudes, and homilies. The ideology the party believes in, socialism, has been discredited all over the world, including in our country (the party has given up its earlier diffidence and equivocation about its ideological orientation; after its victory in Delhi, policy chief Yogendra Yadav made it clear that the AAP is indeed socialist). Yet, the AAP has inspired a large number of people, many of them from middle and upper middle classes: they not only voted but also campaigned for it.

‘Identification’ politics

To a large extent, Kejriwal’s appeal lies in his sincerity—or apparent sincerity, as his critics would say—and his ability to identify with the people. He doesn’t dress or talk like a conventional politician; he looks like one of us—‘us’ here connoting the urban middle class. He is not a great orator, but he is a good communicator. It helps: impressive orators are professional politicians; they speak and we listen to them; we admire them; they are ‘them’; Kejriwal is one of ‘us.’

More than anywhere else in the world, ‘identification’ politics matters in India. Mahatma Gandhi began it. Before him, Congress leaders were gentlemen and dressed as such; after him, they embraced the khadi code and dogma. Gandhi was not the most erudite or eloquent of leaders, but he identified himself with the people—and thus went on to become the most prominent luminary of the nationalist movement. In recent times, Lalu Yadav played the identification card with considerable proficiency.

Another factor that went in Kejriwal’s favor was his perspicacity to read people’s exasperation with corruption. Indians have a Rip van Winkle-like attitude towards corruption. They suffer it, tolerate it, live with it; for years, even decades, it is accepted as a fact of life and of politics. And then, almost suddenly, people get disgusted by ubiquitous venality; they ‘wake’ up and attack anybody remotely connected with corruption. This is how V.P. Singh became prime minister. And, as abruptly as corruption becomes a big issue, it soon becomes a non-issue. It took more than two decades after V.P. Singh for corruption to become politically relevant. More than anybody else, Kejriwal discerned people’s exasperation with corruption; his discernment, along with his diligence, has been duly rewarded.

Poverty of political philosophy

The most important cause of the AAP’s rise, however, is the inability of the Indian mind to rationally approach political and public issues.

Modernity brought many changes in India but, unfortunately, it could not make the Indians rational in the arena of political philosophy. Regurgitation of stale theories passes off as original thinking and sentimentalism is mistaken for profundity; Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru are prime examples.

The intellectual wasteland of India has produced a holier-than-thou Kejriwal, the Naxalite Manish Sisodia, and the jihad-friendly Prashan Bhushan. Earlier, they were cagey about their ideology. In its FAQ section, the website of the AAP tried to evade the subject of whether it was Leftist:

We are very much solution focused rather than ideology driven. There is an age old tendency to pin down political parties as left, right, center etc. In the process everyone forgets the issues at hands and their solutions. Our goal is to remain solution focused. If the solution to a problem lies on the left we are happy to consider it. Likewise if it is on right (or in the center) we are equally happy to consider it. Ideology is one for the pundits and the media to pontificate about.

This might have given the impression that the party is not doctrinaire in its approach. Yogendra Yadav has dropped the mask of pragmatism.

The big idea

At the same time, the AAP government under Kejriwal has also begun in earnest to execute the agenda it promised. This is in sharp contrast to what Atal Bihari Vajpayee did when he became prime minister; he sought to improve upon the Congress system of governance; he was for continuity with some change.

Kejriwal’s big idea is the mohalla sabha. According to a report in The Indian Express,

The AAP’s idea of the mohalla sabha will not only require the city to be mapped into nearly 2,700 mohallas, but will also see huge administrative reorganization of the Delhi government. Members of the AAP said apart from dividing the city into around 2,700 mohallas that will become the centre of decision-making once the ‘Swaraj’ law comes into effect, each sabha will have officials from different departments, who will look at the problems that residents of the sabha bring up.

The AAP hopes to turn the top-down approach upside down. It wants to replace the “closed-door lobbying” with “open-door decision-making.” The party is working on the nitty-gritty of mohalla sabhas, each of which will have a secretariat under an elected representative. “Every member of the mohalla above the age of 18 will vote for this representative. It is the mohalla that will decide what scheme to undertake, and it will be the job of the secretariat, which is essentially an administrative body, to carry out of these decisions. Each sabha will have a bank account to carry out infrastructure and other development works, with the old MLA development fund scheme done away with,” Sanjay Singh, member of AAP’s political affairs committee, told the newspaper.

How all this pans out will be keenly observed not only by the people of Delhi but also of other parts of the country.

Mohalla sabhas and other governance initiatives of the AAP are of local level; they don’t involve ideological positioning. While working at the municipal level, and later showcasing this as a worthy achievement, the AAP can gain heft and acceptability. Meanwhile it may continue to mouth generalities on weightier issues like foreign direct investment, economic reforms, employment generation, relations with Pakistan, illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, and war on terror.

Small expectations

One good thing that will help Kejriwal is the backdrop: the record of the Congress and the BJP at various levels of governance in the national Capital is so dismal that even a little good thing done by the new party would stand out.

At present, it is advantage Kejriwal. Many believe that he may hurt the prospects of Modi and the BJP. But he may be a bigger danger to the grand old party. After all, he decimated the Congress in Delhi, while the BJP—despite the late announcement of its chief ministerial candidate and a generally lackluster campaign—managed to emerge as the largest party. It would be interesting to see if the AAP is able to beat the Congress to emerge as the biggest Left-of-the-Centre party.