Fighting for India: Britain vs. Russia in the Great Game

What happened in the Galwan Valley should not have happened. Yes, China backed away. Yes, there was no loss of land, but the fact remains that we were fighting on the Indian Territory and the best we hoped for was that the enemy would back away. Upon China doing so, we felt vindicated. This should not have been. And to think that just around seventy years ago India had no border with China.

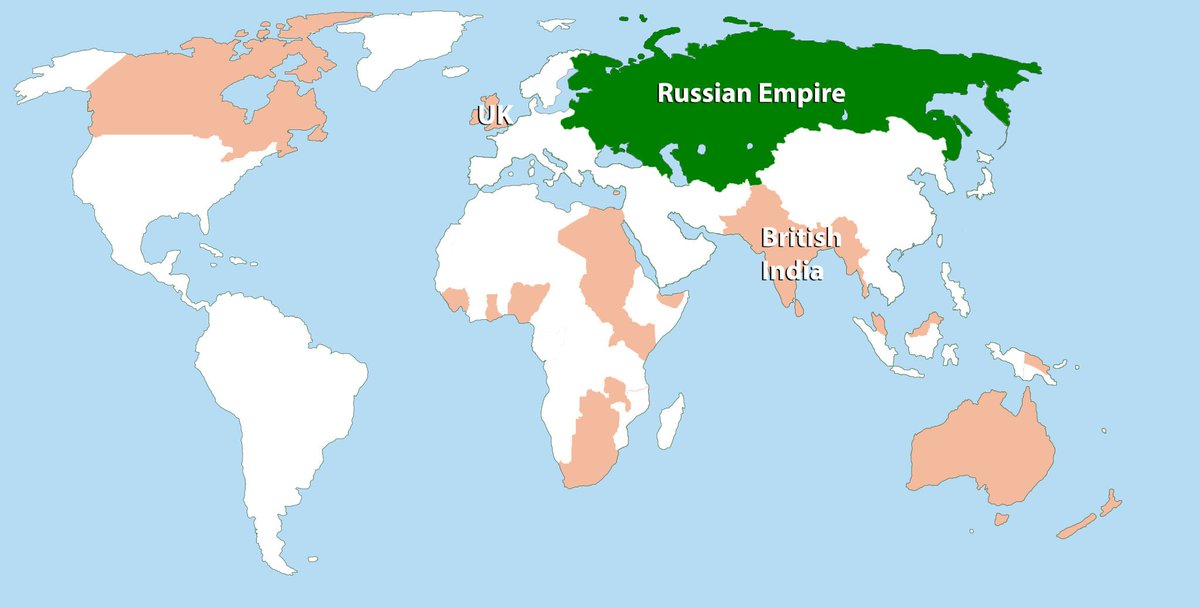

How in 1950-51 India, for the first time in history, came to share a border with China is the final chapter in the story which is better known by the name of ‘the Great Game’. The First Great Game started in the 18th century between Britain and Russia.

Tsarist Russia was ever-expanding in Central Asia to approach towards India’s borders for the real intent of taking over the control of India. Britain, then in frenzy, proceeded to protect India’s borders at any cost and for this created great natural defenses, buffer states and puppet kings and a ring of spies all throughout Central Asia.

This massive game to counter the great threat to India’s territorial integrity was called the Great Game. The name became popular only in relation to the threat to India from Russia. But later on, many other players became important in this game like China and the U.S. This is how Peter Hopkirk describes what the canvas of the Great Game was:

“The vast chessboard on which this shadowy struggle for political ascendancy took place stretched from the snow-capped Caucasus in the west, across the great deserts and mountain ranges of Central Asia, to Chinese Turkestan and Tibet in the east. The ultimate prize, or so it was feared in London and Calcutta, and fervently hoped by ambitious Russian officers serving in Asia, was British India.” (Hopkirk 2)

Responding to the ‘Yellow Peril’

It all started in the Middle Ages. The Mongol Empire spread from China in the East to Russia in the West. Before the Mongols the Russians had been a disparate lot, backward tribes inhabiting the almost uninhabitable, cold and frigid lands of Europe. The preeminent city of Russians at that time was Kiev. But then the Mongols came and defeated the Kievan Rus, and established the Golden Horde. Its brutal yoke continued for around four centuries. (Figes 360) Finally, Moscow under Ivan III defeated the Mongols. (Risanovsky 65)

But the threat of the ‘Yellow Peril’ remained in the minds of the Russian rulers and this is what framed their foreign policy and geopolitics for all eternity to come. In order to ensure that the Yellow Peril does not come marching again on horsebacks, the Russian generals started proceeding East, annexing vast lands in Siberia with the help of its battle-hardened troops – the Cossacks. Gradually they colonized all of Siberia and reached the very heart of Mongolia from where the Yellow Peril originated.

However, they did not stop there. They proceeded on to secure even more borders, break more frontiers and expand more and more. While the Western European states created colonial empires through the ocean route, the Russian Empire created its huge colonial empire on land.

Proceeding towards Central Asia

The Russians then turned their attention towards the vast steppes of Central Asia. The desire to control more lands in Central Asia had taken root in the heart of Peter the Great himself but he was more occupied on the other side of the Caspian Sea in pacifying the warlike tribes of the Caucasus, many of whom were Muslim.

Catherine the Great, the next great dictator of Russia also wished to proceed towards Central Asia, but even more sinisterly than that, it is said that she had harbored hopes of one day actually attacking and annexing India which was under the British sphere of influence then. For that, they had to first annex the Central Asian cities.

The French Threat to India

This is when the British started getting alarmed by the advance of Russia. But something else, even more sinister was brewing up elsewhere. France had lost the race to control India to the British and was confined to a few pockets of influence. The prize went to Britain and India as a colony became the envy of all great colonial powers.

Feeling swindled, insulted and rebuffed, the French were itching to get back to Britain. When their greatest general Napoleon Bonaparte rose in the golden age of modern France, the French felt that this was their time to wrest India from Britain. Napoleon started thinking of attacking India from either Egypt via sea or from Persia and Afghanistan via land route. Though this was always a very farfetched plan even in the heydays of colonialism, any such plan was taken as a real threat because almost all colonial powers in the West created their empires in far-flung places.

What made this plan more sinister was the fact that Napoleon was thinking of ganging up with Alexander I of Russia to jointly attack India in which Russia would attack from Central Asia and France would attack via Persia and Afghanistan. This is what alarmed the British who immediately set about to strengthen India’s borders, create buffer states, make puppet rulers and swing spies all over the continent. Emissaries were sent to the Shah of Persia and the Emir of Afghanistan with the intent of enrolling their autonomous help in case the Russian Bear invades India from the North.

The Great Age of Spies

A massive culture of British spies patrolling Central Asian lands in disguise began. It was the great age of exploration and the Empire was not in dearth of young and adrenaline crazy explorers who had a healthy dose of patriotism too, running through their veins. These adventurous men like Charles Stoddart and Arthur Connelly roamed the desert wastes of Central Asia as well as its cold deserts. Most of these Central Asian cities were Muslim and very fanatically so.

These adventurers crammed the Quran and learned the Arabic language along with native tongues to pass off as Muslim pilgrims and report to their masters back in London and Calcutta. This is a sign of how vigilant the British were. Not only were they securing India’s immediate borders but also creating buffer states. But not satisfied enough with that they were swinging spies thousands of miles away just so that their colonies remain safe. This level of commitment to geopolitics pays off and is actually a necessary thing for a superpower. They did not stop at this either. When they lacked British officers they recruited young Hindu men from India who knew the mores, customs and terrain of Central Asia and ran them as spies. Hopkirk says:

“Certain areas were judged too perilous, or politically sensitive, for Europeans to venture into, even in disguise. And yet these parts had to be explored and mapped, if India was to be defended. An ingenious solution to this was soon found. Indian hill men of exceptional intelligence and resource, specially trained in clandestine surveying techniques, were dispatched across the frontier disguised as Muslim holy men or Buddhist pilgrims. In this way, often at great risk to their lives, they secretly mapped thousands of square miles of previously unexplored terrain with remarkable accuracy.” (Hopkirk 5)

Just imagine about the battle-readiness of a superpower which used to train local Hindus from India for topographical surveys in Central Asia, with secret equipment and secret diaries. And they managed to accomplish this with remarkable accuracy. This also tells us a very remarkable fact. That Hindus and Indians never lacked the ability to pull stupendous feats across seven seas and foreign lands. Our people can battle the worst of terrains in the world if only the policies guiding them are correct.

The Great Game Begins

Napoleon’s plan came to naught as he first attacked Russia in 1802. This proved to be his undoing and he lost with a battered army following him back to France. He never rose like before. Emboldened from this victory, Russia became even stronger and started making serious inroads for its annex India plan from Central Asia.

Russian generals had started sending spies to central Asian Muslim khanates even before the British. Russian General Muraviev petitioned to King Alexander of Russia that the ‘Russian traders’ and ‘travelers’ in Muslim cities were imprisoned, tortured and treated despicably and in order to save his subjects, the Tsar had to invade Central Asia. Muraviev was the first Russian Great Game player.

Officers of British East India Company were not sleeping either. One of them William Moorcroft had been petitioning his superiors to send spies to Central Asia. He was the first Great Game player of Britain. Trying to reach Central Asia from India, he was the first white man to set foot in Leh, Ladakh. Founding his way to Bokhara, he found that Russian merchants and a few soldiers were already there, selling their merchandise and influencing the Khan of Bokhara.

Moorcroft explored many ways to Central Asian Muslim khanates, exploring new paths in Afghanistan and Ladakh, paths that were new to at least the greater world. He died around Oxus and his grave still lies on an important military route. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, this was the route that it took.

After Moorcroft the Great Game became even more intensified. Sir Robert Wilson was a hawk of the British Empire who was too conscious of the approaching Russian threat to India in Central Asia. Another Colonel of the British Army, Lacy Evans made sure that the Great Game from British side would proceed in earnest and thus began the great age of Indian spies in Central Asia and the great age of exploration and mapping of Central Asia:

“A succession of young Indian Army officers, political agents, explorers and surveyors were to crisscross immense areas of Central Asia, mapping the passes and deserts, tracing rivers to their source, noting strategic features, observing which routs were negotiable by artillery, studying the languages and customs of the tribes, and seeking to win the confidence and friendship of their rulers. They kept their ears open for political intelligence and tribal gossip – which ruler was planning to go to war with which, and who was plotting to overthrow whom. But above all, they watched for the slightest sign of Russian encroachment in the vast no-man’s land lying between the two rival empires. By this way or that, what they learned eventually found its way back to their superiors, who in turn passed it on to theirs. The Great Game had begun in earnest.” (Hopkirk 119)

The First Afghan War

The second great player of the Great Game from the British side was British officer Arthur Conolly. It is Conolly who gave the term Great Game to the world. He travelled under disguise to various Central Asian khanates and in the process mapped various cities ruled by Muslim despots which had previously been completely unknown to the wider world.

In Central Asian towns of Khiva, Bokhara and Khokand, the three most important garrison towns of Central Asia, British and Russian spies were trying to outdo each other. British spies like Arthur Conolly were also trying to free a former British spy Charles Stoddart who was thrown in a Bokharan prison by the fanatic Muslim ruler of the city.

While the British were primarily focused on convincing the rulers of these Khanates to become allies of Britain, Russia was directly intent upon annexing and defeating these garrison cities. At first, the Russian efforts were also disastrous and in 1838 in an attempt to defeat the great garrison city of Khiva, their army also had to turn back through snow deserts and lost most of their pack animals and also most of their soldiers.

Conolly argued that there were only two routes through which a Russian Army could invade India. One involved taking the garrison cities of Khiva followed by Balkh and then Kabul. Russia was advancing well in Central Asia. And the other route lay by taking Heart (Herat), the Afghan city. In both cases, Afghanistan was involved. This focus on securing Afghanistan for securing India’s borders would govern British policy towards India’s natural defenses for the next many decades.

The British policy also veered towards discovering and navigating northern and western India’s rivers in order to find their navigability. But this meant going through the terrain of Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab. In order to appease him, some of the best horses were sent to him through the river route. The officer who governed this mission was Alexander Burnes, another great player of the Great Game. Burnes explored more pathways to Central Asia and Afghanistan and one of his aides was a Kashmiri Hindu Mohan Lal whose job was to record all the intelligence gathered during the travels of Burnes. He was fluent in several languages. Without him, these expeditions would have been impossible.

It was the travels of Burnes and some other British officers which convinced Britain that it was necessary for Britain to get hold of Afghanistan once and for all. But this was easier said than done. The western frontier of India at that time was dominated by the Empire of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. He had a formidable army that was capable of fighting against any European power. The Maharaja was in good relations with the British and the British had a treaty with him. Thus Punjab was secure.

But at the same time, in order to secure the western passage to India meant either controlling Afghanistan directly or at least having a treaty with its leader Dost Muhammad. Russia had convinced the Shah of Iran to attack Herat, the Afghan city and had Herat fallen it would have been a massive boost to Russia’s efforts in the Game. But fortunately for the British Shah’s siege was unsuccessful. Now all that remained for Britain to do was to convince Afghanistan of being firmly on the side of Britain

The problem was that Dost Muhammad was an enemy of Ranjit Singh and the British could have a treaty with one or the other but not with the two of them together. And Ranjit Singh was too formidable a player to be made an enemy of. Thus, the British thought of replacing Dost Muhammad with a rival claimant called Shah Shujah who would actually function as a puppet of the British. Shah Shujah had once ruled Afghanistan and ever since he was deposed he was living on a pension in India. Thus, the British invaded Afghanistan on the pretext that they were simply re-enthroning Shah Shujah the legitimate ruler of Afghanistan.

In 1839 the British Army invaded and defeated Dost Muhammad and Shah Shujah became the ruler of Afghanistan. However, it soon became apparent that his position was untenable and he could only be kept in power with constant British military presence in Kabul. By 1842 this was thought to be impractical and the British Army planned withdrawal of the army. This retreat was supposed to be peaceful but the Afghans attacked the army and its stragglers in many skirmishes. More than 16,000 thousand Indian soldiers of the British army and their camp followers were brutally massacred by the Jihadis of Afghanistan.

Britain then sent an army to take revenge and it did, but it was clear that maintaining a puppet ruler in Kabul was not easy and Afghanistan was left to its affairs for a decade. However, none of the players of the Great Game would remain quiet and would continue to consolidate their positions in the intervening years, only to jump into the game with more fervor.

References

- Figes, Orlando. Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia. Penguin, 2003.

- Hopkirk, Peter. The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia. John Murray, 2006.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas. A History of Russia. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Click here to read the previous part of this article.

Featured Image: Quora

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.