On The Nair Community Of Kerala And Their Sambandham System

Introduction

There are many misconceptions and accusations against the Sambandham unions which were prevalent among Nair community and Nambuthiri Brahmin community of Kerala. Many have accused and attacked Kerala Brahmins for being lecherous and Nair women of practicing polyandry, i.e. the custom of wife having multiple partners at the same time, and hence they were promiscuous. For example, noted author and politician Shashi Tharoor has written in one of his books the following [1]

“In Kerala, the men of the Nair community only learn that their wives are free to receive them by seeing if another man’s slippers aren’t outside her door.”

This led to many controversies in recent times. Many online websites and blogs have tried to shame the Nairs and Nambuthiri Brahmins by citing the age-old Sambandham system.

Was polyandry widespread among Nairs? Did Nair women had affairs with more than one man at the same time? Were Nair women of old promiscuous to keep multiple partners? Did Nambuthiri Brahmins indulge in such perverted practices? Let’s do a bit of analysis on this extremely controversial matter in this post.

Who are the Nairs?

The Nairs were the ruling nobility and warrior community of Kerala during pre-colonial times. Marumakkathayam or matrilineal inheritance through nieces and nephews was the most important element of a Nair family. The ruling clans of Kerala styled themselves as Samantan or Samanta Kshatriyas and held names like Varma, Thampan, Thirupad/Thirumulpad, Thampuran, Raja, etc. Samantans and Samanta Kshatriyas were restricted to royal households and formed a very small amount of population. Even though they held higher social and ritualistic rank, they were of the same cultural stock as Nairs because they too followed the same marriage and inheritance system like Nairs and often intermarried with Nairs. Many prominent ruling Nair families also gradually adopted royal Kshatriya names. For instance, Rajas of Vadakkumkur and Thekkumkur kingdoms are recorded as Nairs [2] even though they have Varma name, Palakkad royalty to this day holds Shekhari Varma title while they are Nair-Menons [3], Koratti Kaimals of modern Thrissur district also styled themselves as Varmas [4].

There were many powerful and influential Nair landlords and nobles under these ruling clans as well. For example Anjikaimals, Paliath Achans etc in Kochi, Ettuveettil Pillamar and other Nair Madampis in Travancore, various Nambiar and Nayanar clans in Malabar like Chuzhali Nambiar, Vengayil Nayanar, Kalliat Nambiar, etc. All of them owned vast amount of land and had their own soldiers under them.

There were also various subdivisions among Nairs like Kiryathil, Illathil, Swarupathil, Akatthu & Puratthu Charnavar, etc and Unnithiri, Vellodi, Eradi, Nedungadi, Adiyodi, etc having higher Samantan rank. Nairs also kept various titles like Kartha, Menon, Pillai, Kaimal, Nambiar, Nayanar, Panicker, Unnithan, Valiyathan, Kurup, etc.

A Nair household is known as Tharavad, while among the ruling families the palaces are popularly known as Kottaram or Kovilakam.

In between Brahmins and Nairs, there was also another community named Ambalavasis consisting of diverse groups of people who practiced both matrilineal and patrilineal lineages as well. As the name indicates, they mostly took care of temples and were less numerous. Various castes like Variyar, Pisharodi, Chakyar, Unni, Nambeeshan, etc are included among Ambalavasi sects.

Origin of Nairs

The origins of Nair community are shrouded in mystery. Many authors have stated that the ancestors of Nairs are in fact Nagavamshis or warrior tribe which had a serpent cult. The serpent worship among Nairs is a widespread phenomenon. Each Nair Tharavad or household had a separate place for Sarpa Kavu or a sacred grove dedicated to Nagas. Nair women also wore Nagapadathali or necklace with amulets in the shape of a cobra hood and also tied their hair into the front as a bun symbolizing the hood of a cobra. This hints at their affinity with the Naga serpent cult. However, it is to be noted that royalties of Kerala also traced origins to other Kshatriya lineages. For example, the Samuthiris of Calicut affiliated themselves with Agnivamsha of the lineage of Fire [5], Cochin Rajas to Suryavamsha or lineage of the Sun as they belonged to Chera lineage [6] and Kolathiri royalty in north Malabar ultimately to Chandravamsha or lineage of the Moon [7], etc. So it would be good to consider that ‘Nair’ is an umbrella term for the ruling or military community of Kerala which includes various subdivisions, just like Rajput in northern India refers to descendants of various royal lineages and clans. Indeed, we have cases of people from other communities being absorbed into Nairs For example, Mevada Thampans or Meenachil Karthas trace Rajput origins from the house of Mewar in Rajasthan [8], The royalties of Pandalam and Poonjar trace origins to the Tamil Pandyan lineage of Madurai, Mannadiars of Palakkad region also became absorbed into local Nairs and they were originally from Tamil lands as well. So, it is clear that there were assimilations over many centuries among the ruling and military elites of Kerala from different lineages. However, it could be possible that the Nagavamshis would’ve laid the core foundation of widespread Naga worship in Kerala. They would’ve arrived in Kerala after the Tamil Sangam age from northern regions like Ahichchatra (Ahi-kshetra, the land of serpents) along with waves of Brahmins during the Kadamba era since Malayali and Tulu tradition as well remembers Ahichchatra as original homeland and Kadamba king Mayuravarma inviting them to settle in south. We have no evidence of a community like of Nairs existing in Kerala earlier during the time of Sangam age Cheras. Sangam age literature makes no mention of Nairs in Kerala. So they must have arrived after the Sangam age, starting 3rd century CE. We find place names like Nayarkhanda in parts of Karnataka during the early medieval period [9], so they must’ve arrived from further north during the same time.

As for matrilineal succession, it’s possible that this already existed in Kerala since ancient times among certain groups, or it would’ve been introduced by the groups who came along with waves of Brahmins [10].

Martial Tradition of Nairs

Whatever the origins of Nairs maybe, it is clear that they existed in Kerala at least during the time of the second Chera kingdom or the kingdom of the Chera Parumals of Mahodayapuram or Kodungallur in central Kerala starting from 8-9th century CE. The Perumal era inscriptions make mention of Nairs as consisting of the nobility and militia of Kerala back then [11]. They also make mention of Chavers or Nair suicide fighters who fought against the expanding Cholas. Even today a Chera era Nair organization named Onnu Kure Ayiram Yogam is associated with Kodungallur Bhagavati temple dedicated to Goddess Kali which is located in the former capital of Cheras. Local chronicles from texts like Keralolpathi also talk about the commander of the Chera army being a Nair named Padamala Nair.

The primary occupation of Nairs in old times was ruling and military service. Although people from other communities served in armies, most of the warriors of old kingdoms were drawn from Nairs. In fact, Pada-nair or ‘Nair warrior’ became a common name for soldiers in Kerala. The Nairs were experts in the martial art of Kalaripayattu. Even in the 19th century, we find descriptions stating that it was mandatory for the Nair families to register the name of their children in Kalaris or military schools [12]. They were sent to Kalaris at a very young age and trained to become warriors in service of the kingdom. Many Nair Tharavad ran their own Kalaris. For example, the four Nair households, namely Puthumana, Chandrathil, Vayankara and Verkott in the Valluvanad kingdom of Malabar which supplied suicide fighters or Chavers to the Valluvanad Raja ran their own Kalaris. Every 12 years, they supplied warriors who pledged to die in the battlefield at Mamankam festival against the forces of Samuthiris of Calicut. Mamankam was the national festival of Kerala, which later turned into a battle zone. The military commander and the Kalari Gurus of Samuthiris were also Dharmoth Panickers, another elite Nair family. Few Nairs took up other jobs, like being barbers, washermen, etc of the Brahmins and royalties, but they only formed a minority of Nair subdivisions even during the early 20th century. It is clear that the traditional occupation of Nairs was to serve their king until their death. Many Nair kingdoms of Kerala had a history of conflicts with the Portuguese, Dutch, British and Islamic invaders.

Nairs and Vedic tradition

Although most Nairs were considered only Shudra in Kerala’s peculiar Varna system, most of them were given functions of Kshatriyas. It was mandatory for Nairs to take oath for protecting cows and Brahmins when appointed in the military of the kingdom or when a new king takes up the throne [13]. Nairs are also said to be the guardians of Vedic rituals conducted in Kerala [14], they also traditionally acted as the sacrificer of animals in Vedic rituals conducted in Kerala. The Soma plant used in Vedic Soma rituals conducted in Kerala was also obtained from a Nair chieftain named Kollengode Nampidi from the modern district of Palakkad. Whenever a Yajna was conducted in Kerala, it was only them who supplied the materials used in Yajna like the Soma plant and animal hides [15].

Thus, the Nairs had close association with Vedic culture as well.

It is stated in local texts like Keralolpathi which details Parashurama legend that Lord Parashurama himself established the Nairs as the overseers (kannu ‘the eye’) executors (kai ‘the hand’) and maintainers of law & order (‘kalpana’ or command) in Kerala.

Matrilineal and Marriage System of Nairs

What made the Nairs famous among anthropologists is their matrilineal tradition and marriage system. Though matrilineality was practiced by a few other communities in Kerala, it was dominant among Nairs. The family was managed by the eldest uncle and property succession through nephews and nieces. Mothers and maternal aunts also had a significant role to play in old Nair Tharavad.

As for marriage system, it was a complicated thing among Nairs of old. First there was a ‘mock marrriage’ of girls before they attain puberty. This was called Talikettu Kalyanam. In this ritual the ‘groom’ would tie a necklace or Thali to Nair girls before they attain puberty and stayed in the girl’s house for a certain number of days until celebrations lasted. If there were multiple girls in a Tharavad, then one ‘groom’ may tie Thali to all those girls in a single event. After this ritual, the ‘groom’ may leave the home and may never come back. The girl also had no reason to keep the Thali, she may remove it if she wished to. Talikettu Kalyanam was also practiced by other castes, but the Nair version is unique since there was no obligation for the ‘bride’ and ‘groom’ to spend the rest of their lives with each other. This ‘mock marriage’ was to ensure the fertility of the girls once they go through puberty and the role of the ‘groom’ was purely ritualistic in nature. But today, Thalikettu Kalyanam refers to standard marriage and Thali is a symbol of the chastity of a woman towards their husband, though such a concept was nonexistent during old times. If the family couldn’t arrange a ‘groom’ then the mother of the girl herself would tie the Thali to the girl, with a sword or an idol as representing the groom [16].

After Thalikettu, during her first menstruation, there was another event named Thirandu Kalyanam. This was to celebrate the menstruation of the girl and her attainment of puberty.

After both these events, once the girl attains maturity, she had the liberty to choose her ‘real’ groom who would be her husband. If she wishes she could also take the person who tied the Thali earlier as her husband. This union was known as Sambandham, which was a simple event that included handing over of the cloths to the bride by the groom. After that, the wife stays in her maternal home and the husband would become a visitor to her. Nair women would also have hypergamous unions with royal men, Brahmins and other higher-ranking Nair subcastes. It is to be noted that divorce was easy in Sambandham unions. The wife and husband may freely break the relationship and move on to another partner. This was adopted to suit the military life of Nairs, so that if the husband dies in a battle, the wife can move on and avoid widowhood. Though in many cases, Sambandham indeed lasted throughout life. Any children born in Sambandham unions stayed with the mother’s family and inherited the mother’s property. They had no say in their father’s property. It is also to be noted that even though second marriage after divorce is allowed, it was looked down upon and didn’t involve celebrations as the first marriage, as the 1891 Madras census says [17]:

“Sambandham is, strictly speaking, dissoluble at the will of either party without any formal ceremony being gone through for the purpose, but that will is controlled by public opinion which views with disfavour divorces made for trivial reasons. In cases of divorce, the children always go with their mother. Their legal guardian is their uncle, or karanavan (managing member) of the mother’s house. Both widows and divorced women are allowed to remarry, but the second and subsequent marriages of women are not celebrated with even as much formality as the first marriage. The man goes to the woman’s house with friends, and giving her betel-leaves and nut or dresses, takes her to wife.”

Misconceptions Regarding Sambandham Among Nairs

As stated in the beginning, the Sambandham system had led to many controversies and misconceptions associating with polyandry. Most of the mentions about Nair women having multiple Sambandham partners comes from accounts of foreigners who visited Kerala during the pre-colonial era. Most of these descriptions would’ve been done to explain the lifestyle Pagan Hindus in a bad light. They called Hindus of Kerala as primitive Pagans and demon worshipers. For example, the famous ‘demon of Calicut’ is a sketch of a Hindu deity depicted as a demonic being in Samuthiri’s Calicut kingdom by Lodovico de Varthema in 16th century [18].

Clearly they had nothing but contempt for the Pagan Hindus, and hence they would’ve exaggerated many things about Hindu lifestyle back then. Another thing is that there are many non-factual accounts in foreign descriptions as well. For instance many authors who visited Kerala had written that the kings of Kerala were Brahmins [19]. But this is simply not true, for instance Samuthiris who ruled Calicut kingdom were Nairs belonging to Eradi clan. The rulers of Kolathunad, Cochin and Travancore were also not Brahmins.

Some foreign travellers had also stated that the Samuthiris would kill themselves in every 12 years and pass on the kingdom’s rule to his heir. This is again false, they would’ve mistaken the significance of Mamankam festival hosted every 12 years in Kerala [20]. Such bizarre practice was never recorded in any native Malayalam source. This simply shows that the foreign accounts are really prone to misunderstanding and misinterpretations of native customs, especially when things are complicated like it was in Kerala.

Another thing is there could’ve been confusion among non-Hindus about the marriage set up among Nairs. As pointed above, Nairs underwent to sort of ‘marriages’. One being a mock marriage or Thalikettu Kalyanam and the other being Sambandham or actual union between the couple. The Sambandham could also be broken at the will of either party and they could move on to have another relationship. The foreign authors would’ve mistaken both of them as standard marriages in the European sense, hence would’ve deduced that the Nair women had more than one partner. This is not surprising as foreigners never would’ve gotten a chance to observe Nair rites closely since they always had to maintain distance from the Nairs due to rigid social rules which existed back then, and would’ve been confused about the Nair rites.

As Cochin census 1901 report states [21]:

“ Of all such reflections, if they refer at all to the society of our own times, it may be emphatically asserted that they are all unreal assumptions and inferences drawn or derived from superficial impressions and second-hand information. Several considerations enter into a fact so complex as the modern matriarchal Tarwad of Malayalis, and the observers from outside are in the majority of cases without the means to determine complicated relations and to ascertain matters of fact.”

It is to be noted that there are also other authors who argued that Nair unions were not plural at once, but the woman could divorce and take another partner. For instance, one source from the 19th century says the following about Nair Sambandham [22] :

” Among all these various classes of Sudras marriage is unknown. The women are permitted to form connexions according to their own choice and pleasure for a longer or shorter duration with men of their own or other higher castes. It is however incorrect to suppose that they are permitted a plurality of husbands at the same time. A woman may have but one Bhartava or husband, though she is certainly at perfect liberty to dismiss him and receive another. By some, it has too been incorrectly stated, that the brothers of the Bhartava are also admitted to equal privileges with himself. Though repeated change of the Bhartava is permitted, it is regarded as a disgrace to the woman, and as indicative of a licentious disposition, that this should occur frequently and without sufficient reasons. “

William Logan, the collector of Malabar in the 19th century also notes that the Nair marriages were rigidly observed, respected and jealously guarded [23]:

“ The statement that the younger cadets of Nambutiri families live with Nayar women merely reproduces in English the Malayali mode of describing the married life of these people and of the Nayars. It is part of the theory that the women they live with are not wives, that they may part at will, and that they may form new connections. This part of the Malabar law has, in the hands of unenquiring commentators, brought much-undeserved obloquy on the morality of the people. The fact, at any rate of recent years, is that, although the theory of the law sanctions freedom in these relations, conjugal fidelity is very general. Nowhere is the marriage tie—albeit informal—more rigidly observed or respected, nowhere is it more jealously guarded or its neglect more savagely avenged.”

Samuel Mateer who was a Christian missionary in Travancore writes that brothers may share partners if any of the brothers were unable to or unwilling to take care of the wife [24]. This may be true, but this was only done occasionally probably by men who are poor and unable to take care of the wife alone. When one brother dies, the other may maintain the wife and children. Also, this was not a universal custom among all Nairs.

No anthropologists from the 20th century had stated first-hand accounts on Nair polyandry, all descriptions are only from supposed informants and earlier travelers into Kerala. No Nair today would’ve ever heard of such a practice in their families, they have no memory of it at all. In my own maternal family, we know about our ancestors tracing 5 generations back and although matrilineal set up existed back then, there is no memory of such practice of polyandry.

Even by assuming that such a system existed among Nairs as Mateer says, it is clear that paternity had a big role to play in a Nair’s life. For instance, Kathleen Gough, who argues on the practice of polyandry among the Nairs, states that a Nair woman could be excommunicated from the caste or even executed if she didn’t name the father of the child while she’s pregnant. The men also had obligation to take care of the wife during pregnancy and gifted their children presents during every important festivals [25]:

“ This they did by making gifts to the woman herself and to the midwife immediately after the birth. Any man who had visited the woman in the appropriate time period was required to make these gifts. If a man refused, he could be called upon by the caste assembly to fulfill his obligation. The gifts comprised two new lower cloths for the mother and one cloth and a quantity of paddy as payment to the Nayar women barber who attended at the delivery. Again, than gifts were clearly legal and ceremonial tokens rather than objects of substantial economic value. Legally, however their transfer was of the utmost significance. For if no man would consent to make the delivery payments, the woman was assumed to have had sex relations with a man of lower caste or with a Muslim or a Christian. Her caste assembly would temporally excommunicate her taravad until she and her child had been driven out by their karanavan and the woman’s funeral rites had been performed. The woman, presumably with her child, might be executed by her matrilineal kinsmen or allowed to become a slave of the district chief or the king. If the woman and her lover were publicly exposed even before the birth of the child, both might be put to death.”

Gough, however, doesn’t explain how this is possible in a supposed polyandrous society where women had multiple male consorts. One of the consort will have to take up paternity and take care of the woman during pregnancy and childbirth. This is of course impossible in a polyandrous society since no man would come forward to take the burden of giving expensive gifts and taking care of the pregnant wife and children who are not of his own and is of unknown paternity if the women had multiple partners. So this situation is impossible if we assume that a polyandrous system was widespread among Nairs.

Husbands had Close Relations with their Nair Wives and Children

Clearly, husbands and fathers had an important role to play in Nair’s married life, even though the children had no say over their property.

Here are a few instances where it is evident that fathers indeed had good relations with their children.

1) The entire property of a Nambuthiri Brahmin was passed on to his Nair wife belonging to the Samuthiri royalty of Calicut since he had no other heirs [26]. This would have been impossible if the husband had no role to play in the wife’s and children’s matters. This shows the close bond between the Brahmin and his Nair children.

2) One of the Nair Chaver (suicide fighters of medieval Kerala) named Kandar Menon visits his wife’s household before taking his final journey to battle at the Mamankam festival as recorded in a ballad. His teenage son named Ithappu also accompanied him in the journey. They both fought the battle together and died together in the battle. This shows close relations between the Nair father & the son, even though the son belonged to the mother’s household. There is also another ballad associated with a different Chaver named Chengazhi Nambiar of Cochin. When he and other Nairs took oath to become suicide fighters, all from the families including their wives and children mourned as recorded in the ballad [27].

3) The Cochin Maharajas claimed origins from the sister of last Chera king who was married to a Nambuthiri Brahmin landlord from Perumbadappu region. This Brahmin later gave his entire property to the royal lady & the kingdom came to be known as Perumbadappu Swaroopam. [28]

4) Similar was also the case with Payencheri Nairs, who were children of Sarkara Kovilakam belonging to the royalty of Kodungallur. The Raja gave his property to his wife & children [29].

5) In royal households, men indeed have close relations with their children. The children of Maharajas of Travancore also were honored by the name ‘Thampi’ & had special privileges compared to ordinary Nairs. Venad (later Travancore) Maharaja Rama Varma (uncle of famous Anizham Thirunal Marthanda Varma who expanded Travancore kingdom) supervised the education and training of his sons (Thampimar) as recorded in the ballad. He gave them royal privileges of training to ride horses and elephants and was happy seeing the Kalari training of his sons. Later, he also gave many grants to the Thampis as gifts. This simply proves that the father-son relationship was close even when matrilineal tradition flourished in Kerala back then.

Venad Maharaja Rama Varma married a non-Malayali lady named Abhirami. She was later admitted as a Nair’s wife of the king & his sons too became Thampis (Nair subcaste in Travancore, children of Maharajas and other royal princes). The folk song on Thampimar says that he raised sons by himself even though matrilineal tradition existed [30].

6) One of the largest landlords of Malabar, Vengayil Kunhiraman Nayanar spent his childhood at his Brahmin father’s Illam. His father Haridasan Somayajipad was Vedic Brahmin who performed Soma Yajna [31].

7) A Kaimal landlord, as stated in a Vadakkan Pattu or ballad of Malabar, had two daughters, he married them off to his nephews Unikkonar Nair and Unichandror Nair [32]. It was a cousin marriage (which was also prevalent among many other southern Hindu communities). In fact, Murappenu (niece) or Muracherukkan (nephew) was considered an ideal partner for a Nair’s own son or daughter among Nairs. How is this possible if fathers had no contact with their children or had no role to play in their marriages? Even today Marumakan (nephew) or Marumakal (niece) also refers to son-in-law and daughter-in-law.

8) Kuthiravattathu Nairs were children of Samuthiri Rajas of Calicut [33]. They were bestowed with many rights by Samuthiris as their Samantan rank. They held Kshatriya titles like Thampan.

9) The Raja of Kadathanad married off his own daughter to famous Nair warrior Thacholi Othenan [34]. Though Marumakkathayam succession existed, this shows that Raja had the right to choose the groom for his daughter.

10) The famous Carnatic musician and poet, Irayimman Thampi or Ravi Varman Thampi was named after his Grandfather who belonged to Travancore royalty. He maintained close relations with the royalty and also played an important role in the life of famous Travancore Maharaja Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma. He composed the famous Malayalam lullaby Omanathinkal Kidavo for Swathi Thirunal [35].

All the pieces of evidence only show that men in Nair Sambandham unions did have close contact with their children. There are more evidences for close relations between Nair’s husband and wife. For instance in a ballad of southern Kerala named Iravikuttipillaiporu mentions that the wife was in grief after her husband, the commander of Venad (later Travancore) Nair army, Iravikutty Pillai, fell in the battle. She and his mother tried as much as they can to stop Pillai from going for the battle [36].

Now how is this possible if polyandry indeed was the widespread custom with wives having no relations with husband other than sexual contact and the paternity of the children was unknown?

Another thing to note is that Thiruvathira festival was widely celebrated by Nair women too. This festival is dedicated to husbands by their wives, as an epitome of chastity, devotion and love towards their husbands. The women would fast on this day to please Lord Shiva and Devi Parvati for the wellbeing of their husbands and married life as an ideal couple. It’s very much like Karva Chauth in northern India. Women would also perform a dance form named Thiruvathirakkali. This would be impossible if polyandry was widespread among Nairs. Clearly, this well-recognized tradition is widely practiced till date among Nairs itself argues against the claim of the widespread practice of polyandry among the Nairs.

The kings of Kerala also married Nair ladies, they too were honoured with the title ‘Amma’ or ‘Mother’ as called by the citizens. In North Malabar it was Kettilamma, in central Kerala it was Nethyaramma and in Travancore, it was Panapillai Ammachi. Hence, the Nair women held a great and respectful position in the society as consorts of the kings.

Conclusion

So to conclude, polyandry was not a widespread mainstream custom among Nairs. Most Nair women may have new Sambandham unions in her lifetime, but not at the same time. Also, we should remember that men too had the liberty to choose different partners. Even if polyandry was in practice in some localities, it was on certain uncommon circumstances as Mateer had stated and certainly it was not widespread and accepted norm among all classes of Nairs.

Also, the paternity of children had an important role in Sambandham unions, and if the paternity was not determined, it resulted in the ex-communication of the entire family from the caste. Husbands had a liability to take care of their wives during pregnancy as well and once they become fathers, they had to visit their children and offer them gifts every often. Women also had strict restrictions based on subcaste and region on choosing their partners. For example, a Nair woman of north Kerala would not choose a partner from southern regions since it is forbidden for them, and would be excommunicated if she does so. Hence, with these rigid restrictions, it is unreasonable to shame Nair women and Brahmins as promiscuous.

The Nambuthiris led a strict religious life. Only the elder brother in a family would marry from within the community and preserve the property without divisions. Younger brothers often married into royalties and other Ambalavasi or elite Nair women and spent most part of their life on religious studies. It is because of the deep religious tradition the Nambuthiris came up with advanced Kerala school of mathematics and astronomy, preserved ancient Vedic rituals and also authored works like Manameyodaya on Mimamsa tradition. Nambuthiris excelled in Tantric tradition as well, for example, there are works like Tantrasamuchayam and Seshasamuchayam which elaborates on the Tantric tradition of Kerala.

It is absurd to label the entire community of these much-respected scholastic people as promiscuous.

Sambandham unions were not ‘free sex’ and nor it is to be compared with prostitution like many anti-Nair and anti-Brahmin authors do. It is also not true that the Nambuthiri Brahmins ‘exploited’ Nair women or the Nairs themselves gave up their women to Brahmins.

Nambuthiri Brahmins were and still are a small minority in Kerala, despite being the highest priestly caste in Kerala. Most of the Nambuthiris married Nair women belonging to royalty and nobility. Most Kings of Kerala had a Brahmin father or grandfather because of this reason. While on the other hand, most of the usual Sambandham unions were between much more numerous Nair subcastes themselves.

References:

[1] The Great Indian Novel By Shashi Tharoor

[2] Perumals of Kerala by MGS Narayanan

[3] Palakkattussery Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/717234848459983/photos/a.717251338458334/1247790828737713/?type=3&theater

[4] നമ്മുടെ ഇരിങ്ങാലക്കുട (Our Irinjalakuda) Facebook group

https://www.facebook.com/groups/ourijk/permalink/2036379489813430/

[5] Samoothirimar by PCM Raja

[6] Perumals of Kerala by MGS Narayanan

[7] Vadakkan Aithihyamala by Vanidas Elayavoor

[8] mevadathampans.com/index.html (Archived https://web.archive.org/web/20160303171519/mevadathampans.com/index.html)

[9] A History of South Kanara: From the Earliest Times to the Fall of Vijayanagara by KV Ramesh

[10] Perumals of Kerala by MGS Narayanan

[11] Ibid

[12] History of Travancore from the Earliest Times by P Shungoonny Menon.

[13] Zamorins of Calicut: From the Earliest Times to A D 1806 by K V Krishna Iyer

[14] Madrs District Gazetteers: Malabar Volume 1

[15] The Nambudiri Ritual Tradition with Special Reference to the Kollengode Archives, by M. R. Raghava Varier in Agni, the Vedic ritual of the fire altar by Frits Staal

[16] Castes and tribes of southern India (volume 5) by Edgar Thurston

[17] Census of India 1891. Volume XIII Madras The report on the census

[18] Demon of Calicut https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Demon_of_Calicut.jpg

[19] The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires: Volume I By Armando Cortesão

[20] Francis Buchanan-Hamilton as cited in Malabar Manual by William Logan

[21] Census of India 1901 Volume XX Cochin, Part I Report

[22] A Gazetteer of Southern India: With the Tenasserim Provinces and Singapore by Pharoah and Co

[23] Malabar Manual by William Logan

[24] Native Life in Travancore by Samuel Mateer

[25] Matrilineal Kinship by David M Schneider & Kathleen Gough

[26] Zamorins of Calicut: From the Earliest Times to A D 1806 by K V Krishna Iyer

[27] Calicut : The city of truth revisited by MGS Naraynan

[28] A Translation of a Record, Grandhavari, in the State Archives by Kerala State Archives Department

[29] The Dutch in Malabar, being a translation of Selections Nos. 1 and 2 with introduction and notes by A. Galletti,

[30] Venadinte Kathaganangal. By Thikkurissi Gangadharan

[31] വാസനാവികൃതിയുടെ കഥാകാരനെ ആരെങ്കിലുമോര്ക്കാറുണ്ടോ?https://www.azhimukham.com/vengayil-kunjiraman-nayanar-malayalam-literature-author-vasanavikruthi-history-memory/amp

[32] Puthariyankam by Thikkurrissi Gangadharan

[33] Zamorins of Calicut: From the Earliest Times to A D 1806 by K V Krishna Iyer

[34] Vadakkan Pattukal by M C Appunni Nambyar

[35] Biography of Irayiamman Thampi http://keralasahityaakademi.org/Writers/PROFILES/IrayimmanThampi/Html/Irayimmangraphy.htm

[36] Iravikkutty Pilla Poru Oru Padanam by Thikkurissi Gangadharan

(Special thanks to Twitter user @Hondubvll for providing me with additional sources and information to expand the article).

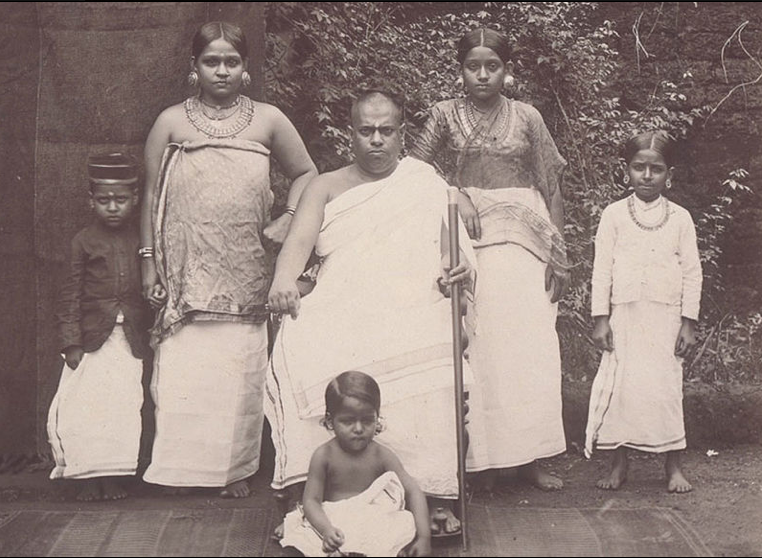

Featured Image: Raj Vichar

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.