Skills for Life and Livelihood: Revive the Old Approach to Education

Education in India has always been a symbol of pride and heritage. Delivery of quality education to all has been a prolonged effort post-independence.

Presently, India is one of the world’s fastest growing economies in terms of GDP share (PPP), only behind China and US (World Bank Report 2011). The ‘Global Economic Prospects’ report published by World Bank in January’2015 forecasted that by 2017 India will out-pace China in terms of GDP growth rate.[1] The country sits on a most advantageous situation with 65% of its population being under the age of 35 and approximately 12 million individuals on an average are expected to join the workforce every year. With these demographics, it happens to be world’s youngest nation with median age of 27 years.

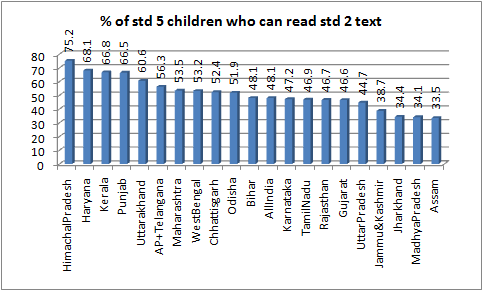

However, the ability of the nation to reap maximum benefits out of this better-off is doubted when the quality of our education system is bothering. Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2014 mentions though the enrollment levels in Indian schools are 96% or higher for the 6-14 age group but 25% children in Std-VIII and 50% in Std-V cannot read Std-II level textbooks and 19.5% children in Std-II cannot recognize numbers.[2] National University of Education Planning and Administration (NUEPA) also mentions concern over the quality of learning in its document titled ‘India: Education for all- towards quality and equity’ published in August’2014.[3] And so does National Achievement Survey (NAS) 2014 conducted by NCERT [4].

With this huge grey area in terms of quality of education in the Indian Education System we cannot expect our generations to have a future of vast opportunities. This definitely paves way for poor employability, and subsequently social degradation. Quoting in this regards further, the India Skills Report 2015 released by CII with People Strong and Wheebox that finds only 39.36% (18-21 yrs), 34.13% (22-25 yrs) and 30.48% (26-29 yrs) graduate/under-graduate candidates employable out of 300,000 tested all across India,[5] and most lacked basic employability skills of communication and numerical/logical ability. These statistics certainly threaten the aspirations of comprehensive development and maximizing the demographic dividend in India.

Elementary Education- The Founding Level

Elementary education (EE) in India is the only compulsory level of education extended as a right to all children in the age group 6-14 years. The concern starts from this level itself, when after so many years of independence there has been focus on Universalizing Elementary Education, and after more than a decade of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, education was given as a right to children just few years ago. Moreover, since 28 years we have not had any National Policy for Education. Even so, there have been continuous reports on poor basic learning standards in our schools. Children, who struggle to even read, write and comprehend general concepts during basic education level and somehow get through to higher levels of education, shall definitely have poor skills for life as well as livelihood subsequently.

There is a serious need to look at education as a breakthrough in the vicious circle of poverty. Education is the index of nation’s sustainable development apparently. Just as GDP reflects prosperity of the nation at a point of time, the level of education in a country reflects its ability to sustain development over time. Developing nations should not devalue the importance of education. It empowers the population of the country and strengthens the society. The theories of education and contribution of education philosophers of India, relevantly emphasizes providing universal and compulsory education to all children along with imparting skills for life and livelihood through basic education.

Philosophical Perspectives

Primarily, as common man understands, education aims at imparting knowledge. It is this knowledge that requires a global outlook and a synthesis of various types of information and experiences. This relates to the philosophical aspect of education that forms of the base of any education system across the globe. As Plato defines, “True education, whatever that may be, will have the greatest tendency to civilize and humanize in their relation to another’, which is still the most widely accepted theory of education based on humanism.[1].

The Indian education system ever since the Vedic age was propounded on same humanist principles essentially, extending it to the path of salvation. Historian Altekar has rightly remarked in this context that Indian education has been ‘regarded as a source of illumination and power that transforms and ennobles our nature by progressive and harmonious development of our physical, mental, intellectual and spiritual powers[2].’ The contemporary Indian philosophers of education have also furthered the same essence of education. Their theories seem to be based on the ancient Upanisadic thought, extending to Neo-Vedanta philosophy. Whether it was Sri Aurobindo, Vivekanada, Tagore or Gandhi, ‘all these philosophers with minor differences among them have maintained what can be called Integral Humanism, which is the philosophy of our age.’ (G.R Sharma, 2003).

Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya

The doctrine was developed by educationist Pt Madan Mohan Malviya. In his view, ‘education must be given to all as he believed that poverty lies in the ignorance of people. He realized the importance of education for social and economic development. He advocated compulsory primary education in India and universal elementary education for overall development.

He linked importance of elementary education with agriculture and industrial education, mentioning that it provides the base for technical and specialized education. Malviya’s philosophy of education based on Integral Humanism emphasized education to be a tool for overall development of personality.[3]

The Gandhian exposition on aim of education is remarkable here. It mentions that ‘education is ought to be a kind of insurance against unemployment’[1]. In his words, “The child at the age of 14, that is, after finishing 7 years course should be discharged as an earning unit. … Even so the State takes charge of the child at age-7, and returns it to the family as an earning unit. You impart education and simultaneously cut at the root of unemployment.”

The ‘Wardha Scheme of Basic Education’ postulated by Gandhi reflecting the same ideals contained education through handicraft for skilling children in order to make them self-reliant later in life, establishing direct relationship of knowledge and life. It advocated mother-tongue of the child to be the medium of instruction, and child to be the centre of education system while teachers to be the main pillars of the entire system. It was focused on overall development of the child–his body, mind and soul. It provided for systematic and organized knowledge delivery to the child. It adequately provided for teachers’ training as well[2].

The Indian Philosophy of Education looks at education as a path towards salvation, primarily based on Integral Humanism, which is further based on the attributes of life– body, mind, intellect and soul, related to kama, artha, dharma and moksha, respectively. And since, elementary education–the founding level of education is the only compulsory channel of education in India, it is relevant to emphasize ‘skills for life and livelihood’ through this basic level of education. This in turn is the key to sustainable development of the country withal.

Complex system and missing links

The skill component emphasized here, for Elementary education can be broadly categorized as Basic Employability skills, which includes basic numeracy, arithmetic, language skills, general awareness, cognitive ability, career planning skills, etc and Life skills, which includes self awareness, problem solving, decision making, creative aptitude, social skills, emotional skills, etc. The existing education framework mostly contains it all through National Curriculum framework or Minimum Learning levels framework, etc. The problem is where these policies don’t find effective practice in light of obsolete, non-responsive and poor governance mechanisms.

The focus of policy interventions has been more on providing the ‘essentials of education’ with more quantitative approach, and less on the ‘governance part’ indicating lesser importance given to the qualitative approach. The competition and monitoring is seen to be based more on providing quantity of infrastructure than on quality infrastructure, in most of the States. Moreover, when implementation of policies with respect to school education largely depends on the State(s), there are no links to ensure uniformity in basic indicators of quality. Neither the system is induced through competition to bring the states at par on certain basic parameters.

Then, till now there was no concrete mechanism and effort to address the challenges in implementing the RTE Act. Several clauses of the Act have created confusion and worsened the learning systems at the grass root levels. Non-detention policy (NDP) is the most evident example of this, which was brought to retain children and control drop-outs, but resulted in motivating absenteeism and caused disinterest in studies on the part of most of the children and their parents (Geeta Bhukkal Committee Report).

The ‘Language Disadvantage’ in our classrooms that deters learning (Mohanty et.al. 2009) has found no profound consideration in our policy framework yet. With regards to Teachers availability and training, the system has been most inconsistent. The sick states in terms of learning are those where availability of trained teachers has been a consistent issue. The recent NSDC report on Skill gaps (Vol.8, 2015) has even put a question on the skills of existing trained teachers, and even on the training methods of the DIETs. %age of professionally trained regular teachers is 80.06 in 2013-14 (78.58 in 2012-13), while that of contractual teachers is 55.55 in 2013-14 (54.01 in 2012-13).[1]These are some of the contemporary concerns and issues in the existing framework which deter delivery of these essential skills through the compulsory level of education in India.

Finding a Way Forward for Sustainable Development

[contextly_sidebar id=”vyQayxgaR6y3u6LFNLzCAm5ytFgOcHWF”]

The new government formed under NDA in 2014 was voted to power for development, which is of course not possible with poorly skilled people. In order to meet the aspirations of the people and to sustain it over time, there is a strong need to revive the old approaches dying at the hands of the complex system and to bridge the missing links in the existing system rigorously. The NDA government seems to have caught this nerve and is seen to be committed towards the same gradually. For instance, when the country didn’t have any National Policy for Education since last 28 years, the new government has called for a participatory and comprehensive process to formulate the new National Policy for Education.[2]

The consultative new education policy formulation process, in its most comprehensive form is covering from 2.5lac Gram Panchayats to the State Governments and includes other relevant stakeholders too, reflecting the approach of finding the missing links from the grassroots,assimilating the practical challenges and then carving the way forward. The 13 themes designed for School Education and 20 themes for Higher Education for consultation in this context comprehensively cover all aspects.

It can be expected that the new education policy will provide concrete measures to bridge the existing disconnect in policy and practice, gives way to contemporary and innovative approaches for quality education, and revives the Indian philosophy of Education of skill development for life and livelihood through the basic level of education. After all, children are the future of the country. Education system providing these basic skills prepares them for life and makes way for sustainable development of the country as such kind of education transcends poverty and underdevelopment.

[1] Education for All (EFA) report 2014, available at http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/upload_document/EFA-Review-Report-final.pdf

[2] http://mhrd.gov.in/consultation-framework

[3] GEP Report, World Bank 2015 available at http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects/summary-table

[4] ASER 2014 press release: http://img.asercentre.org/docs/Publications/ASER%20Reports/ASER%202014/pressreleaseeng.pdf

[5] http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/upload_document/EFA-Review-Report-final.pdf

[6] http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/document-reports/Main%20Report%20NAS%20Class-3%20%28cycle-3%29-Final.pdf

[7] India Skills Report 2015: https://wheebox.com/logo/India%20Skills%20Report2015.pdf

[8] Sharma, G.R. ‘Trends in Contemporary Indian Philosophy of Education- A Critical Evaluation’. 2003.

[9] Altekar, A.S. ‘Education in Ancient India’. 1934.

[10] Tiwari, Jyotsna. ‘Madan Mohan Malaviya: Statesman, Parliamentarian and Educationist.’ 2013. (Bundelkhand University)

[11] Gandhi, M.K, ‘Harijan’. 1937.

[12] Pathak, R.P. ‘Education in Emerging India.’ 2007.

[13] Education for All (EFA) report 2014, available at http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/upload_document/EFA-Review-Report-final.pdf