Svādhyāya: Studying our Holy Books- III

[contextly_sidebar id=”315L3wFaW5XhhajmW3E4KK0xY2ACivPv”]

In this part we discuss the relative importance of scriptures vis-à-vis Dharma and Moksha.

Scriptures and Dharma- Their Relative Importance

With all the benefits of studying scriptures, it must be clarified that even the study and recitation of scriptures is no substitute for good conduct and pious living. One cannot wash his hands off goodness and perform evil actions thinking that his scriptural learning will save him.

The Vedas cannot help a man who does not have a virtuous conduct, even though he may have studied them together with the six Vedāngas. At the time of his death, the Vedas abandon such a man, just as birdlings fly out of their nest when they become adults.

Indeed, all the Vedas together with the Vedāngas and the Yajnas, can bring no joy to a man devoid of good conduct, just as a blind husband derives no joy on seeing his beautiful wife. Vasishtha Smriti 6.3-4

A Brahmana whose conduct is evil does not reap the fruit of Vedic study. Conversely, a Brahmana who shows appropriate conduct reaps the entire fruit of his Vedic study. Manusmriti 1.109

Study of scriptures is only one of the virtues of acts of Dharma. Dharma is much more than studying scriptures. They who are masters of scriptural learning but are evil in their conduct have merely wasted their time in studying the holy books. Therefore, scriptures are a means to knowing the difference between Dharma and Adharma, and not a substitute for practicing Dharma.

Scriptures and Moksha (The Final Goal) – Their Relative Importance

Hinduism also does not consider study of scriptures as the final goal. Unlike Abrahamic faiths, Hindus are not strictly a ‘book-religion’. Although long revelatory and other sacred texts exist in hundreds (‘Mahabharata’ in 100,000 verses is the longest poem in the world), they are merely considered as a guide to experience and realize the Supreme Reality, which is beyond all books and intellectual enterprise.

What good can the Vedas do unto him who does not know that Great Being, who is All-pervading and Eternal, Holiest of all, Who sustains the Sun and the Earth, and is the support of the learned, the method of Whose realization is the chief aim of Vedic teaching? But they alone enjoy eternal bliss who study the Vedas, live a righteous life, become perfect Yogis and realize God. Rigveda 1.164.39.

The purport of all Scriptures is Brahman (Supreme Being) indeed, and this is known when their passages are considered harmoniously. Vedānta Sūtra 1.1.4

After studying the scriptures, the wise person who is solely intent on acquiring spiritual knowledge and realization, should discard the scriptures together, just as a man who seeks to abandon rice discards the husk. Amritabindu Upanishad 18

As is the use of a pond in a place flooded with water, so is that of all Vedas for a Brahmana who is enlightened spiritually. Gita 2.46

The mere study of the letter of the scriptures does not have much benefit. One should first study the scriptures, try to understand their essence and finally practice the same to achieve the final goal of their teaching – spiritual realization. Moksha is the final goal of our life, and therefore also the final goal of scriptural study. If scriptural learning does not advance one’s understanding of God and lead us closer to Moksha, then it is of no use. And when the goal is achieved, the scriptures have no value left because the means of reaching the goal are of no further use once the goal itself is reached.

How to and How not to Study the Scriptures

As state above, a study of scriptures and following their teachings is a pre-requisite to advancing in Dharma and Moksha. However, many people study the scriptures with the wrong intentions, or they believe that they are very Dharmic and are entitled to Moksha just because they have mastered the scriptures. The following parables from the Hindu tradition teach the correct and the wrong ways of studying the holy books.

- Live the Scriptures, do not just memorize their Words

Studying the scripture is not an end in itself. Once, a man came to Swami Chinmayananda and said, “I have gone through the Gita fifteen times.” Swami-ji asked, “But has the Gita gone through you even once?” The story below illustrates this message very aptly-

Studying the scripture is not an end in itself. Once, a man came to Swami Chinmayananda and said, “I have gone through the Gita fifteen times.” Swami-ji asked, “But has the Gita gone through you even once?” The story below illustrates this message very aptly-

“While touring South India, Chaitanya encountered a certain Brahmin in the temple of Ranga-kshetra. This man daily sat in the temple turning over the pages of the Bhagavad-gita, but his constant mispronunciation of the Sanskrit made him the object of general mirth and derision. Chaitanya, however, observed signs of genuine spiritual ecstasy on the Brahmin’s body, and he asked him what he read in the Gita to induce such ecstasy. The Brahmin replied that he didn’t read anything. He was illiterate and could not understand Sanskrit. Nevertheless, his guru had ordered him to read the Gita daily, and he complied as best he could. He simply pictured Krishna and Arjuna together on the chariot, and this image of Krishna’s merciful dealings with his devotee caused this ecstasy. Chaitanya embraced the Brahmin and declared that he was an “authority on reading the Bhagavad-gita.”[1]

- Do not study scriptures to show-off, but for self-transformation

The story of Vāmana Pandit below shows how mere learning of Gita and other scriptures does not benefit us spiritually. We become ‘alive’ only when we give up our ego and pride, when our heart is filled with devotion, and when we are able to teach the scriptures to the common man in a simple language out of love and compassion.

“Vāmana pandit was born in a Brahmin family of Bijapur, which was under Muslim rule. Even as a young boy he could compose Sanskrit verses. When the ruler Adil Shah heard of this child prodigy, he offered to support the boy, if he embraced Islam, so the family sent him secretly to Varanasi to study under some scholars. After studying there for about twenty years, Vāmana became quite famous for his knowledge and skill at debating. He used to go on tours and challenge other pandits to a debate. Hearing of Ramadasa, he decided to visit him and challenge him also to a debate. When he arrived near the place where Rāmadāsa was staying, Vāmana pandit sent a messenger to get Rāmadāsa. Vāmana waited and waited under a tree, but by midnight Rāmadāsa had still not come. At that time, he happened to see two ghosts, and overheard them talking about him. The ghosts were saying that Vāmana would soon be joining them. Vāmana pandit became very afraid. He thought about what the ghosts had said and gradually understood that his egotism and pride of scholarship was leading him to hell. In fact, he became so repentant that he decided he would approach Rāmadāsa for spiritual instructions.

“Vāmana pandit was born in a Brahmin family of Bijapur, which was under Muslim rule. Even as a young boy he could compose Sanskrit verses. When the ruler Adil Shah heard of this child prodigy, he offered to support the boy, if he embraced Islam, so the family sent him secretly to Varanasi to study under some scholars. After studying there for about twenty years, Vāmana became quite famous for his knowledge and skill at debating. He used to go on tours and challenge other pandits to a debate. Hearing of Ramadasa, he decided to visit him and challenge him also to a debate. When he arrived near the place where Rāmadāsa was staying, Vāmana pandit sent a messenger to get Rāmadāsa. Vāmana waited and waited under a tree, but by midnight Rāmadāsa had still not come. At that time, he happened to see two ghosts, and overheard them talking about him. The ghosts were saying that Vāmana would soon be joining them. Vāmana pandit became very afraid. He thought about what the ghosts had said and gradually understood that his egotism and pride of scholarship was leading him to hell. In fact, he became so repentant that he decided he would approach Rāmadāsa for spiritual instructions.

Soon after, at dawn, Rāmadasa arrived and Vāmana pandit bowed down at his feet. Rāmadasa blessed the pandit and after giving him some spiritual instructions, told him to go to Badarika Ashrama, in the Himalayas, and meditate on Vishnu. After practicing sadhana whole-heartedly there for a long time, Vāmana pandit had a vision of the Lord, who blessed him and told him to go back to Rāmadāsa for further instructions. When Vamana pandit met Rāmadāsa again, Rāmadāsa gave him more instructions and told him to go to Shri Shaila Hill to meditate on Shiva. Again Vāmana did as he was told, practicing intense sādhanā for several years. Here also he was blessed by the Lord and told to return to Rāmadāsa. This time (in 1668 CE) Rāmadāsa described to the pandit how the common man needed religious education in their own language. Thus far the pundit had written only in Sanskrit. His learning was learning only among other Brahmin pundits like himself. It was of no use to ordinary people. So Rāmadāsa requested Vāmana pandit to write religious books in Marathi for the common people, and Vāmana agreed. Besides some very beautiful poems, Vāmana pundit also wrote a Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita, entitled Yathārtha Dīpikā.”[2]

- There are no Short-Cuts to Studying the Scriptures, it takes Hard Work

Sage Bharadvāja and his son Yavakrīta were neighbors of Sage Raibhya and his sons. The latter were all great scholars. Many people travelled long distances to study under Raibhya and his children. This made Yavakrīta jealous. But he did not like to study. So, he started praying to Lord Indra. Pleased with Yavakrīta’s penance, Lord Indra appeared in front of him and offered him a boon. Yavakrīta asked that he become a great scholar, so that people should come to study under him, just as they went to study under Raibhya and his scholarly sons.

Sage Bharadvāja and his son Yavakrīta were neighbors of Sage Raibhya and his sons. The latter were all great scholars. Many people travelled long distances to study under Raibhya and his children. This made Yavakrīta jealous. But he did not like to study. So, he started praying to Lord Indra. Pleased with Yavakrīta’s penance, Lord Indra appeared in front of him and offered him a boon. Yavakrīta asked that he become a great scholar, so that people should come to study under him, just as they went to study under Raibhya and his scholarly sons.

But Indra replied, “If you want to become knowledgeable, you should focus on your studies, rather than trying to please me and get the boon of wisdom from me.”

But Yavakrīta would not listen. He resumed his austerities and penance, hoping that Indra would eventually get impressed and bless him with knowledge. One day, Yavakrīta went to the River Ganga to take a bath, when he noticed an old man throwing handfuls of sand into the river current. When Yavakrīta asked him the reason for doing so, the old man said, “People have a difficulty crossing the river. Therefore, I am constructing a bridge across it by throwing sand into the water.”

Yavakrīta was amused, and said, “But you cannot construct a bridge this way because the water will keep washing away the sand that you throw. Instead, you need to work harder and put in more effort and materials to construct the bridge.” The old man replied, “If you can become a scholar without studying, I too can construct a bridge with just handfuls of sand.”

Yavakrīta realized that it was Lord Indra who came disguised as the old man to teach him that worship alone cannot result in scholarship. He therefore apologized to Lord Indra and started studying diligently.

- Scriptural Learning is not a Substitute for Practical Wisdom & Wisdom

“Once several men were crossing the Ganges in a boat. One of them, a Pandit, was making a great display of his erudition, saying that he had studied various books – the Vedas, the Vedanta, and the six systems of philosophy. He asked a fellow passenger, “Do you know the Vedanta?” “No, revered sir.” “The Samkhya and the Patanjala?” “No, revered sir.” “Have you read no philosophy whatsoever?” “No, revered sir.” The pandit was talking in this vain way and the passenger was sitting in silence when a great storm arose and the boat was about to sink. The passenger said to the pandit, “Sir, can you swim?” “No”, replied the pandit. The passenger said, “I don’t know Samkhya or the Patanjala, but I can swim.”

“Once several men were crossing the Ganges in a boat. One of them, a Pandit, was making a great display of his erudition, saying that he had studied various books – the Vedas, the Vedanta, and the six systems of philosophy. He asked a fellow passenger, “Do you know the Vedanta?” “No, revered sir.” “The Samkhya and the Patanjala?” “No, revered sir.” “Have you read no philosophy whatsoever?” “No, revered sir.” The pandit was talking in this vain way and the passenger was sitting in silence when a great storm arose and the boat was about to sink. The passenger said to the pandit, “Sir, can you swim?” “No”, replied the pandit. The passenger said, “I don’t know Samkhya or the Patanjala, but I can swim.”

What will a man gain by knowing many scriptures? That one thing needful is to know how to cross the river of the word. God alone is real, and all else is illusory.”[3]

- Scriptural learning is not a substitute for common-sense

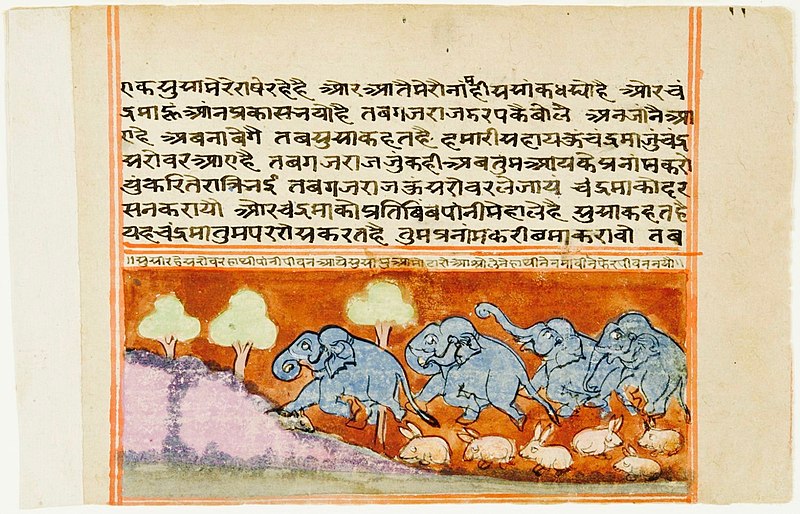

A Sanskrit proverb reads – “Just as a blind man has no use for a mirror, what will he do with scriptural knowledge if he lacks common-sense?” The following story from the Panchatantra illustrates the truth that in addition to mastering the Holy Scriptures, one must also have commonsense.

The Four Pandits and the Lion: There were four childhood friends. Three of them studied a lot in different schools and became very learned scholars. The fourth was not that learned, but he had a lot of wisdom and commonsense. One day, the three scholars met with each other and said, “What is the use of our knowledge if we are not able to make any money out of it? Let us go to the royal palace and get a job with the King. This will make us rich.” The first scholar said, “The fourth among us is not really a scholar. What is the use of taking him with us? Let us leave him behind.’

The Four Pandits and the Lion: There were four childhood friends. Three of them studied a lot in different schools and became very learned scholars. The fourth was not that learned, but he had a lot of wisdom and commonsense. One day, the three scholars met with each other and said, “What is the use of our knowledge if we are not able to make any money out of it? Let us go to the royal palace and get a job with the King. This will make us rich.” The first scholar said, “The fourth among us is not really a scholar. What is the use of taking him with us? Let us leave him behind.’

But the third of them was a kind hearted person. He said, “We have been friends since our childhood. Therefore, it is not fair to leave him behind.” So all the four got together and started walking towards the palace. On the way, there was a jungle. There, they saw a pile of bones lying on the ground. They immediately recognized that these bones belonged to a dead lion.

The first scholar said, “I know how to put these bones together and complete the skeleton of the lion.” He used his knowledge, and within a few minutes, the skeleton was ready.

The first scholar said, “I know how to put these bones together and complete the skeleton of the lion.” He used his knowledge, and within a few minutes, the skeleton was ready.

The second scholar said, “I know how to put blood, skin and muscles into the skeleton.” He too worked for some time, and soon, the skeleton had muscles, eyes, blood and skin on it.

The third scholar said, “I can give life to this animal and make it alive!” Everyone seemed impressed. But, the fourth friend, who was not very scholarly, immediately stopped them and said, “Do not be foolish. A lion eats human beings. If you make it alive, it will pounce on us and eat us.” But the three did not listen to him. However, he begged them to allow him to climb a tree before they make him alive. They agreed.

When the lion came alive, it immediately pounced on the three scholarly friends and killed them. The fourth friend on the tree looked at the dead bodies of his friends and wept. He waited for the lion to go away, and then got off the tree and went back to his village. He said, “I wish that my scholarly friends also had some common-sense.”

- Scriptural learning is useless if it does not make you a better Human Being

Once, a gathering of Rishis took place at Mt Kailash, where Bhagavan Shiva lives. Rishi Durvasa too walked in with a bundle of books in his hand. But he did not greet any of the other Rishis present, and went up to Bhagavan Shiva’s throne, sitting right next to him. Bhagavan Shiva asked him, “Rishi, how is your study progressing?” With pride on his face, Rishi Durvasa replied, “I have studied all the books that I am carrying and have learned them by heart.”

Rishi Narada got up and then said, “Pardon me Rishi Durvasa, but you are just carrying these books like a donkey that carries burden on its back.” When Rishi Durvasa heard these words, he became red with anger, and threatened Rishi Narada, “How dare you ridicule me? I will curse you. Why did you compare me to a donkey?”

Rishi Narada replied, “True knowledge gives humility, forgiveness and good manners. You walked in without greeting others, and sat right next to Bhagavan, instead of sitting at His feet. Does this not show that you have not learned anything even after memorizing your books?”

Rishi Durvasa realized that Rishi Narada was saying the truth. He realized that his behavior had been foolish. In repentance, he discarded his books in the ocean, and left the assembly to do meditation to atone for his inappropriate behavior.

- At the Time of Death, it is not Scriptural learning, but Bhakti that will save you

Once, Shri Shankaracharya was walking along the banks of the Ganga River in Varanasi with his disciples. He saw a very old Pandit, almost on his death bed, trying to master and teach the rules of Sanskrit grammar. Out of compassion, the Acharya composed a stotra of 13 verses, in which he asks humans to seek refuge in Krishna because only He can save us at the time of death. Learning rules of grammar for mere intellectual satisfaction will not save us from death. The 14 disciples of Shankaracharya added a verse each, and collectively, it became a Stotra of 27 verses. This beautiful stotra is called Bhaja Govindam, or Moha Mudgara (a Hammer to shatter delusion).

Once, Shri Shankaracharya was walking along the banks of the Ganga River in Varanasi with his disciples. He saw a very old Pandit, almost on his death bed, trying to master and teach the rules of Sanskrit grammar. Out of compassion, the Acharya composed a stotra of 13 verses, in which he asks humans to seek refuge in Krishna because only He can save us at the time of death. Learning rules of grammar for mere intellectual satisfaction will not save us from death. The 14 disciples of Shankaracharya added a verse each, and collectively, it became a Stotra of 27 verses. This beautiful stotra is called Bhaja Govindam, or Moha Mudgara (a Hammer to shatter delusion).

The stotra teaches the worthlessness of worldly desires and ego and asks us to seek refuge in Bhagavān by chanting His names, reading the Gita, and becoming dispassionate towards worldly pleasures.

References

[1] Rosen, Steven. 1988. The Life and Times of Lord Chaitanya. Folk Books: Brooklyn (New York). pp. 163-164

[2] Parivrajika, pp. 199-200

[3] Tales and Parables of Sri Ramakrishna. Sri Ramakrishna Math. Mylapore: Madras, pp. 58-59

Featured Image: Wikipedia