The Conflict between Tradition and Modernity in India

One can hardly deny that Aatish Taseer writes beautifully, but it is a beauty that has now become so commonplace that it fails to make an impression. It invites you to put your trust in the gorgeous weave of words and be persuaded by their charm, only it is not what you want to do anymore. We have done that with V. S. Naipaul, and Arundhati Roy, and a host of other writers, and enough is now enough. We would like to understand and for doing so, not be encumbered by the wordsmith’s art.

The Interpreters: Among the Brahmins of Benares is an essay recently published by Aatish Taseer. It is an interpretation of an experience encompassing the diverse layers of the Indian reality – each character in this essay, including the author, constitutes a stratum – and what makes it cohere together is the profound sadness engendered by the incommensurability of those layers. Such an interpretation cannot elicit a critique – it can only invite you to apply yourself, if you can, as another inter-twining of tradition and modernity, in this vast fabric that we call India. The current essay constitutes such a response.

The pathos of The Interpreters manifest itself in the characters and the landscapes of modern India, sketched alternately in the essay. I will not bother with the latter where, suffice it to say, we are left with the palpable impression that everything is ugly and ruined. It would be unfair to think of this as an attempt to put down India. Yes, the poetry of a dilapidated India, broken and hopeless, full of rage and woe, has now become insufferable. But this essay is an outpouring of grief and the lamentation extends and pervades the whole of the countryside.

So we turn to the characters who are the human faces of this tragedy. Each one is a curious mix of tradition and modernity, struggling to negotiate between these two kinds of persecution. The purpose of modernity was to free humans from the bondage of tradition. But then modernity also established its own rules which not only mandated that freedom, but also laid down the precise forms in which it had to be given expression, thus imposing a system of bondage of its own. Considering that tradition is a feature of the Indian past and modernity borrowed from the West, neither of which can be properly understood by the Indian who is separated from the former in time and from the latter in space, juggling between the two is a torture that has become the routine of every Indian.

At the two extremes of the spectrum are the author himself, who is an international success in modernity, but utterly bereft of tradition, and a Shivam Tripathi, a Brahmin in Varanasi, who is wholly immersed in tradition but a nobody in modernity. But the essay begins with Sweetie, an air-hostess of Indigo airlines, which carries the cheekily titled Hello 6E in-flight magazine. This also agrees with her smart and stylish uniform, but what more can be said? The author observes that the uniform carries in one part the label ‘girl power’ – suggestive of feminism – and somewhere else it says ‘leading lady’ – suggestive of cheesy glamour. In other words, it is a parody of Indian modernity. But what about Sweetie herself, who has been clothed in that uniform? We cannot tell if women’s rights matter to her or, if they do, then whether gay rights also matter, and even if both matter, whether she is free of caste prejudice? Or perhaps she has accepted modernity and is struggling against the traditional values of her parents, and which may yet also maintain a hold on her? It is not just Sweetie, but the whole of India that is thus dressed in modernity – a modernity that barely understands itself and neither reveals the depth of its penetration nor the battles it wages against the traditions of the person underneath.

Here in this air-hostess, two Indias, one secret and one self-confused, have come together. But sometimes they occur separately as in a posh restaurant in a Delhi mall where a fashionable woman is not so much unhappy with the pasta, which she has been served, not being al dente but with the fact that the waiter, who has served it, has no clue about the meaning of al dente. Then, as master to a servant, modern India makes it her duty to show traditional India her place, to point out her inability to uplift herself to a level at which she could be eligible to serve Italian cuisine. But upliftment involves an act of self-abandonment, for modernity in India does not arise organically from its own past but has been borrowed from outside, in arbitrary forms like the al dente pasta, and it looms over tradition like the shadow of death.

But modernity is just as fragile and vulnerable to the terror of tradition. Without warning, the narrative shifts to Pakistan, as if it was a continuity of India, and the author relates the assassination of his own father for challenging that country’s blasphemy laws. These modernists are the ones whom the author calls as ‘interpreters’ for they are members of a class created by the British as intermediaries between themselves and the Indian masses. Subsequent to the exit of the British, this class retained its power and continued in their role as interpreters of modernity for the traditional world from which they became alienated. The author, identifying himself as a member of this class, reminds us over and over – a sign of the palpability of his condition – that he is colonised, deracinated, ‘culturally and linguistically denuded.’

The rest of the essay deals with the author’s stay in Varanasi. But why has he gone there? For me, here lies the poignancy of this narrative. He says that it is to understand the conflict between tradition and modernity, but it appears to me that he, an interpreter of modernity, wants to find someone to interpret his lost tradition for him and allow him to participate in it. And the anguish touches its high watermark when it becomes clear that the interpreters of Indian tradition can no more interpret it to the interpreters of Indian modernity than vice versa. Like the al dente woman from the Delhi restaurant, the author has become divorced from tradition. Unlike the flight attendant, however, tradition does not rumble for him underneath a forced veneer of modernity. Yet, he is not through with it. There is a keenness to recover it and make himself a part of it. There is a deep sadness in observing its slow death (another poignant connection with Varanasi, since death here does not lead to rebirth) and perhaps, even more so, in belonging to a class that has perpetrated its murder.

But is any of it real? Evidently, the author, safely ensconced in his perch in the West, can afford to sympathize with Indian tradition and its heartbreaking struggle for survival. For the al dente woman living in urban India, on the other hand, it haunts like a spectre from all sides and cannot let her enjoy her pasta – how can she, when the man who has served it cannot even appreciate the exquisiteness of that dish and would not deign to eat such insipid food himself, even if he could afford it? Her rage at him is visceral because merely by his abominable presence he renders her whole existence specious.

This, in my view, is the source of all the angst in this essay. Indian tradition may be deplorable, but its modernity is even more galling. At least the tradition is authentic and therein lies hope – but only for those who are willing to abide by its rules and its sensibilities. The author is evidently not one among them and so his sadness for the ruin of tradition is both unconvincing and impotent. What one apprehends as genuine, however, is the loss which the author has suffered, a loss of belonging and a sense of rootlessness that modernity inflicts on all its denizens as the price of admission into its world. This in turn produces a nostalgia for tradition which becomes the staple of post-modern literature, The Interpreters itself being a fine specimen of this genre.

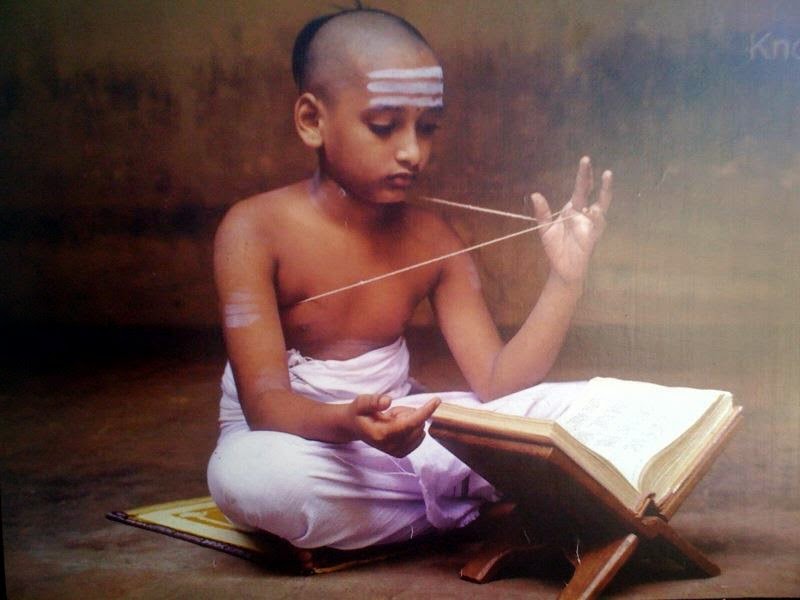

Shivam Tripathi, as I mentioned above, is the interpreter of tradition. He is a poor Brahmin from a village in Madhya Pradesh, who has lived in Varanasi since his childhood, when he first arrived in the sacred city to learn Sanskrit. The author is apparently moved by his piety to describe his gestures in the temples of Varanasi as vividly as he does; and even of complete strangers: the essay also evocatively sketches the movements of a man performing his ablutions in the Ganga. A modern man would likely scoff at them, laugh scornfully at their ignorance and folly, but not our author. He has evidently developed a post-modern respect for tradition which treats it as a form of resistance to normative modernity. It extends to those who uphold it as a matter of faith in the face of a modernity destined to obliterate it, as well as in the face of those who may exploit it in the service of a political ideology. In my view, however, this respect is suspect because it is only under the aegis of a political ideology that tradition has any future at all and the whole point of preventing this union, or as it is sometimes put, of saving Hinduism from Hindutva, is to allow modernity to devour its victim without obstruction.

But is Shivam the proper interlocutor on behalf of tradition? When the author tells him that he is interested in the conflict between tradition and modernity, he corrects him that the contest actually exists between modernity and spirituality (adhyatmikata). From where, I wonder, did Shivam gain this knowledge? Since the nineteenth century onwards, a separation of realms has been organized between India and the West. Spirituality has come to be recognised as the domain of Indian expertise, materiality of the West. India must gain material knowledge from the West as the West must realise spiritual wisdom from India. This division has received blessings from intellectuals on both sides of the divide.

Nothing, in my view, could have been more pernicious for the flourishing of Indian knowledges than this dichotomy. Admittedly, scientific knowledge and technological expertise, which is objective and universal in nature, can be easily transferred from culture to culture. But materiality includes not only the natural sciences, but also social sciences, not only knowledge of the physical world but also about the flourishing of humans living within it. The latter component which includes the socio-economic and political organisation of humans is culture-specific. To have surrendered this domain to the West and have permitted it to dictate the appropriate forms it should take in India, was a grave blunder.

Modern Hindu thinkers, as a result, have disavowed the whole intellectual heritage pertaining to the dharmaśāstras and arthaśāstras, and have fixated their attention on the modes of personal spiritual upliftment – yajna (ritual), puja (adoration), bhakti (devotion), dhyana (meditation), japa (incantation), and the spiritual knowledge of the Veda and Vedanta. Shivam’s diagnosis of the Indian cultural crisis affirms precisely this dichotomy evident from the fact that he reduces tradition to spirituality. The assumption is that for as long as Indians remain loyal to their domain of spirituality, the culture will miraculously prosper. The fact that Shivam, immersed wholly in the great texts of the tradition, living in a city that is the very epitome of that tradition, echoes the idea of modern Hindu intellectuals, which they have themselves learnt through their engagement with the West, reveals just how deep into the Indian psyche, modernity has made its inroads, yet everywhere it remains shaky and superficial, like an ugly scar on a veiled face.

Shivam takes the author to the Kedareshwar temple complex and lets him witness his utter devotion, his faithful reproduction of all the pietistic sounds and gestures. The author realises that the performance is not a matter of rational analysis, but an act of self-transformation brought about by a complete surrender of the self. This, for Shivam, constitutes the essence of Indian tradition, which Indians have betrayed through their romance with modernity. Furthermore, this modernity does not consist for him of an alternate, though equally good and valid, form of knowledge and practices. After exiting the temple, as they reach the holy stairs of the Ganga, he points at some ‘teenage girls in jeans and pink socks with busy designs on their sweaters … taking selfies, screaming and giggling’ and refers to them disdainfully as ‘our modernity.’

All the characters representing tradition in this essay are Brahmins and they are all united in the view that modernity, albeit a threat, is also a travesty. None of them appear to take it seriously and none of them can understand why anyone takes it seriously. In the Indian view nothing is fundamentally a problem, but it becomes one only when it metastasizes and overflows its legitimate jurisdiction. As these Brahmins see it, the issue is not with modernity as such, but that the Indians have lost the balance and allowed it to become too dominant and take over their whole life. While this compels Shivam to see the matter settled once and for all either in favour of modernity or of the way things were, another Brahmin from Varanasi prefers the Indians to lead dual lives – Western on the outside, because such are the exigencies of the contemporary milieu, while remaining Indian on the inside. Raj Kapoor made that same point most poetically when he sang of his heart remaining Hindustani while wearing Japanese shoes, English trousers and a Russian cap.

All of this goes back to that essential dichotomy between Western modernity and Indian spirituality, and the relentless march of devastation shows that the formula is not working. Between the domains of personal spirituality and physical nature, including the body and its needs, there is another domain – a society governed by a political will – on which the intellectual immersed in traditional knowledge is deafeningly silent. For example, if asked about the role of women in society, he will not touch any text on the stri-dharma-paddhati with a barge pole. If he speaks from it, he will not be able to do so persuasively. He has no idea why the rules are what they are and how they can – with or without admissible changes – address women’s issues in the contemporary world. Just as the author mentions that Shivam was annoyed when asked about the leaves, he was offering to Siva, and realised that ‘faith functions by an internal logic; it is its own means of knowing and one does not know by asking questions; one knows by feeling,’ so would be the stand of our interlocutor of tradition. But what works in spiritual matters will not pass muster in the discussion of social issues. On the other hand, even if he realises that obedience is necessarily required for the social text of tradition to work, he will not have enough confidence in its goodness to make a demand for authoritarianism.

The whole of the socio-political realm remains thus a confused zone on which very little is said by the contemporary representatives of tradition, except to express alarm at its conquest by modernity. Thus, Shivam is not happy with the attire and conduct of the teenage girls at the Ganga ghats, but he does not articulate the problem as a social grievance. He sneers at their modernity, but he juxtaposes it against the adhyatmikata of a man steadfastly meditating near them. He simply does not know the existence of a social discourse. He does not realise that it is possible to express the demand for a change in the attire and conduct of the teenage girls as a social good required for a proper living in the world, irrespective of spiritual welfare. Everything, on the contrary, is reduced to spiritualism. It is on account of the decline of spiritualism that society has turned bad. It is on account of the decline of spiritualism that the depredations of modernity have succeeded. If only the Indians become more spiritual, the world around them will improve. That the world is and can be shaped for the good by forces other than spiritual is simply beyond his grasp.

Although these are my views and not those of the author, I think he is trying to say something similar when he describes being moved by the spartan room occupied by Shivam, filled with nothing but some bedding on the floor and a collection of books on a low table, and regrets that it would constitute ‘an education in the humanities’ if the scholar comes ‘to this learning with a spirit of intellectual enquiry rather and not piety’. This is precisely the reason why Shivam, in spite of his vast knowledge, cannot speak to modernity, cannot act as an interpreter of tradition for the author.

The essay outlines the suffering of both Shivam and of the author. Shivam is struggling against a modernity that permits him no avenue while the author is coping with the loss of his tradition. But there is a suffering that is shared by both of them and which brings us readers into its ambit as well – what is to be done about this vast knowledge that lies in the custody of tradition? We are immediately struck by its greatness and we may even speak of its relevance, but when the rubber meets the road, as it were, it doesn’t seem to be making any headway. It is simply unable to gain entry into the contemporary intellectual space occupied by modernity.

Twice in the essay Shivam advises that neither tradition nor modernity is painful in itself, but this persistence of tradition within modernity is painful. In a sense, the author makes the same point when he declares that ‘there is more to civilization than endurance; there is vitality and strength.’ Evidently, there can be neither in a civilization whose tradition has become moribund and whose modernity is superficial. This is best expressed in the author’s own moving words:

‘The Indian failure is of an old culture, decaying for centuries, that will neither die nor serve as inspiration for the future. That miraculous moment, when the seed of something very old fertilises the present moment and produces something utterly new, has not happened. The past is dead weight, and Indian modernity skin-deep, like a top soil that bars access to the nutrients of the deeper earth, but which cannot itself sustain life.’

The author is sympathetic towards tradition, of course, and again and again laments its loss, his separation from it. But that sympathy never translates into a desire to save it, let alone devise a proposal to such an end. Ideally, what the author would like is for Indian tradition to organically produce its own modernity, but he finds this improbable because modernity holds it down under its suffocating grip. Tradition, on its part, holds back modernity and does not allow it develop freely. This tragic state of affairs has now become unbearable not only for all those caught up in its vortex, but even for those watching from their safe havens in the West. Something’s gotta give and in the essay the hammer stroke falls reluctantly on tradition. This is not only the author’s own view, but also that of Shivam, the voice of tradition.

This is not a conclusion with which we may all agree – I certainly don’t – for surely, if tradition is the authentic basis of India, what has been a source of meaning and inspiration to its people for hundreds of years, and the current form of modernity is merely an alien graft imposed by colonialism, then surely it is the former and not the latter that should be selected for survival. The author’s disillusionment with tradition arises from the failure of those who are trained within it to speak of it to the outside world. The final anecdote in the essay involves an aged and sick teacher of a Samaveda school with whom the author faces a difficult time in trying to get him to connect his knowledge with the concerns of modernity. But for the teacher the world outside was on its way to a great dissolution which would occur at the end of the Kali Yuga, which prompted the author to ask him about the value of teaching the Veda under these circumstances. This question, the author tells us, finally struck a chord with the teacher and he gave a profound answer that just as a farmer saves his seeds in the time of flood and sows them again after the waters subside, so through his profession of teaching the Veda he was doing a beej raksha ‘protection of the seed.’ The essay ends on his poignant note: ‘This is what we do, and this is all that can be done.’

These people, who are projected as the genuine representatives of the tradition, but can neither develop a critique of modernity nor make their tradition sensible and valuable to it, appear to fill the author with a sense of hopelessness. Of what avail is it to a man to roll his body tightly against himself and hold it securely in the face of a rising flood? At one point the water will rise to a level above him and the man will drown. Such will be the end of tradition in the hands of its custodians. The stream of people interested in traditional knowledge in each generation will gradually become a trickle, then decline to a few drops and finally dry up.

This is a valid argument, but the conclusion is wrong in my view because the author has not taken all the circumstances into account. I am sure the author knows, but has refused to consider that it will be an aspect of Indian modernity itself that will rescue tradition from its denouement. There are, of course, several modern Indians, who speak of shraddha (faith) in the tradition, but the author realizes – and I would agree with him here – that it is an unworkable proposition, even if the shraddha is genuine. After all, it is not that the custodians of tradition, who have devoted many years of their life to its study, are lacking in shraddha. Rather it is precisely on account of it that they realise that the discourse of modernity is utterly different to anything they have studied and there is simply no way in which they can communicate with it.

In my view, this shraddha factor, combined with the obsession for a spiritual grounding in worldly affairs, is in fact the main obstacle for modern Indians to connect with their tradition in a meaningful way. First of all, the nature of that connection in a modern context would have to be political rather than spiritual. Tradition carries value in modernity only as the basis for the formation of a political community. This, in my view, is a source of real fear for the author and his like-minded colleagues. This use of tradition, which can breathe a new life into it, the author would seek to prevent at all costs. Notwithstanding their romance with tradition, they would like to keep it defanged and declawed, for in the end tradition is about bondage and not freedom, and to modernists and post-modernists such a system can only be oppressive. Hence, they present as its authoritative voices, those who cannot do anything to save it.

Secondly, and more importantly, we have been looking at the wrong traditions in this essay on account of the error, mentioned above, of associating India with the spiritual and the West with the material. The author is interested to meet people among whom ‘tradition was most intact’ and finds it ironical that they ‘were least able to speak of it.’ But the traditions he has sought are pāramārthika (dealing with eternal truths) in their orientation. Yes, they are unable to speak to modernity, but what is their potential to speak to vyavahāra (practical world) anyway? The teacher of the Samaveda school in this essay has nothing to say to modernity but, for that matter, he would not have had anything to say even to the worldly Hindu of pre-modern India who was an expert in the dharmaśāstras and arthaśāstras. The only difference is that modernity treats him like a pariah while the pre-modern worldly Hindu would have revered him. But the pre-modern worldly Hindu would not have approached him for advise in the conduct of vyavahāra any more than modernity considers him relevant in the management of its affairs. The teacher fully understands this limitation. He fully understands that his knowledge cannot bring about any change in vyavahāra. All he can do is keep his knowledge secure – beej raksha as he calls it – and bide his time for vyavahāra to turn favourable. Indeed, that is ‘all that can be done’ by him for it will require a worldly Hindu thinker – a Manu or a Chanakya – who is an intellectual in the field of vyavahāra, to bring about a change in the contemporary form of Indian modernity. These are not the kind of people the author has sought to meet and, indeed, one would not be surprised if he would not want to meet them.

It is a modern assumption based on the conditions which prevailed in the Christian West that vyavahāra in India was rooted in paramārtha. It is this assumption which has produced among worldly Hindus an unhealthy obsession for the other-worldly teachings of Yoga and Vedanta. It is now widely believed by the Hindus, including those immersed in the tradition like Shivam, that vyavahāra has become unbearable in contemporary India due to a decline of spirituality, that ancient India was a prosperous and well-ordered society because of the advanced spirituality of the Hindus in those times.

But what if that is not the case? The existence of dharmaśāstras and arthaśāstras clearly demonstrates that there was a well-identified intellectual domain separate from the spiritual concerns of the moksaśāstras. In the Pancatantra and the Hitopadesa, monks are regularly depicted as charlatans. The Manusmriti cautions us against overtly pietistic brahmanas by branding them as bidala-vratins and baka-vratins i.e. brahmanas with cat-vow and heron-vow. Those who have read the ancient Indian narratives would know that the cat and the heron deceive their victims through a show of dharmic knowledge and piety.

Thus, it appears to me that the pessimism of the author is misconceived. I do not mean to belittle the mokṣaśāstras. Indeed, the treatises the ancient Indians have produced on jnana, bhakti, karma and yoga, may be the best there are for the attainment of mokṣa. But there is nothing they can speak to modern vyavahāra anymore than they could speak to traditional vyavahāra. From their perspective, all vyavahāra – traditional and modern – is avidyā (ignorance). Shivam is therefore wrong. When he interpreted the author’s concern about the conflict between tradition and modernity as one between adhyatmikata and modernity, he committed the fundamental error of projecting it as a conflict between paramārtha and vyavahāra. Such a conflict, of course, exists, but that is an eternal conflict that constitutes the very essence of the human condition and will be with us till the end of time. The conflict between tradition and modernity, on the other hand, is between two forms of vyavahāra, one which prevailed in pre-modern India and one which modern India has borrowed from the West, or between two different systems of pravṛtti-dharmas on which nivṛtti-dharma has nothing to say. From the perspective of the teacher of the Samaveda school, this is a contest between two avidyās and what can he speak to either party who would be equally deluded in his view? Indeed, the tradition of India that can speak to modernity is the tradition of the dharmaśāstras and arthaśāstras – the traditions from which all modern Hindus have been taught by their own intellectuals to turn away in favour of the paths of jnana or bhakti or karma or yoga, as if spiritual advancement is the solution to our worldly problems.

These paths can only equip one with the proper mindset to engage in vyavahāra, but they cannot teach one the actual dos and don’ts of vyavahāra. I don’t think our great Hindu teachers of the last two centuries would have failed to realise so fundamental and strategic a difference. Surely, they would not have been so foolish to believe that as long as the Hindus took care of the former, they would spontaneously realise the latter. No, it appears to me that the whole domain concerned with the dos and don’ts of vyavahāra was wilfully conceded to the West. The plan appears to have been that the attitude to take while engaging in vyavahāra, the Hindus will learn from their sannyāsa traditions, while the constitution of vyavahāra itself, they will learn from the West.

Thus, for example, a principle of worldly life, such as social equality, will be taken from a Western tradition like liberalism, while the spiritual notion which will galvanize the Hindus to abide by this norm, such as the idea that the atmans of all persons are identical with Brahman, will be taken from a monastic Indian tradition like Advaita Vedanta. What the imposition of an ugly modernity on a vitiated tradition, so movingly depicted by the author, shows is just how colossal a failure this project of ‘Hindu Renaissance’ has turned out to be.

The result has been a denudation of the intellectual vigour of worldly (gṛhastha) Hindus, directed towards the study of sannyāsa paths meant for seeking liberation from the world rather than learning the proper ways of living in it, as handed down in the ancient Indian schools of worldly thought. ‘That miraculous moment, when the seed of something very old fertilises the present moment and produces something utterly new, has not happened’ because we have been looking for it in the wrong place. The grand, abstract, universal, pietistic notions of Indian spiritualism can do nothing more than beg to be accommodated as a complement to modernity, as a device to repair its fractured soul, but can never challenge it in any meaningful and fundamental way. It is rather the modest, concrete, worldly, intellectual Hindu schools dealing with the trivarga (triad) of dharma, artha and kāma, which, if we dare to turn to them, can speak to modernity and confront it as an equal adversary.

Feature Image: https://wovensouls.org

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.