Trotting Out the Caste Horse and Flaying It

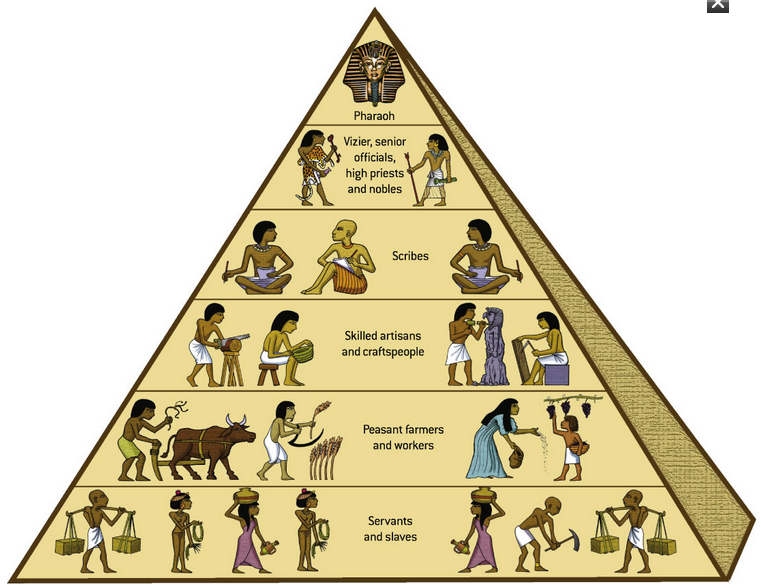

In a recent article (July 1, 2020) in The New York Times, Isabel Wilkerson asserts that three “caste systems” have prevailed/persisted in human history: “The lingering, millenniums-long caste system of India. The tragically accelerated, chilling and officially vanquished caste system of Nazi Germany. And the shape-shifting, unspoken, race-based caste pyramid in the United States. Each version relied on stigmatizing those deemed inferior to justify the dehumanization necessary to keep the lowest-ranked people at the bottom and to rationalize the protocols of enforcement.”

Wilkerson’s longish piece, excerpted from her book, is an interesting narrative, crafted to fit a predetermined political argument and arrive at a set of predictable, provocative, and false assertions. While there are some interesting historical tidbits in her essay, like the visit of a group of African American professors to India some years ago and their visit to a village in Uttar Pradesh, where indeed caste discrimination still continues to be rampant, and how India’s Dalit Panthers Party was inspired by the Black Panthers Party, she also conveniently and wrongly inserts “evidence,” invoking the now dead, defunct Aryan Invasion Theory, saying that “The United States and India… (were) conquered by people said to be Aryans arriving, in one case, from across the Atlantic Ocean, in the other, from the north. Those deemed lowest in each country would serve those deemed high.” Wilkerson, using the analogy/metaphor of a house needing major repairs, seeks to have society do that kind of a major repair on systemic injustice. Sounds well and good, but what really are the concrete proposals she makes that has not already been tried or are in the works?

Wilkerson’s essay in The New York Times was a precursor to the release of her book “Caste: The Origins of our Discontents,” which we are told argues the case that there is an “entire social structure as an unrecognized caste system” in the US. The book is now included in Oprah’s Book Club, and Queen Oprah herself has said that she will be sending out 500 copies of the book to “…the nation’s governors, mayors, CEOs and college professors”. Wilkerson claims that only caste can explain social hierarchy in the US, and how African Americans occupy the lowest rung in that hierarchy. Sure, there is indeed both a problem of race and violence in the US, but we suspect that little study and research has been done to support her assertions about India’s jati/kula system and comparing social hierarchy and social discrimination in India with the problems of race and violence in the US. For example, Durga Das, the intrepid Indian journalist and author, noted this on his visit to the US in 1950: “I visited the Negro ghettoes of New York and Chicago as well as of other cities, and came to the conclusion that these underdogs of the affluent society were exploited alike by well-to-do blacks and whites” (“India from Curzon to Nehru & After”, p. 298). It seems, seventy years later, we see little difference in that social dynamic as the billionaire Oprah interviews the millionaire Wilkerson to discuss systemic injustice while unwilling or unable to carefully focus and tackle the problems besetting the “underdogs”. That, of course, is the problem, we may say with both journalists and generalists: they know something about everything, and therefore can easily jump to conclusions entirely made up of their own superficial reading of and a simplistic grasp on many things, and proposing grand changes without seeking to figure out the nuts and bolts of such operations.

Wilkerson asserts that in human history, “three caste systems have stood out”: the “caste system” of India, the “tragically accelerated, chilling and officially vanquished caste system of Nazi Germany,” and “the shape-shifting, unspoken, race-based caste pyramid in the United States”. In a reference to the Indian jaati/kula practice, and not really to what the Nazis foisted on the Jews or what White Americans claim about race relations, she says that “a caste system endures because it is often justified as divine will, originating from sacred text or the presumed laws of nature, reinforced throughout the culture and passed down through the generations”. But as a scholar friend pointed out, “Caste, in the sense of Jaati/Kula, is not a system of ranking at all. It is a system of grouping, with the features of hereditary occupations, membership by birth, and endogamy; hierarchy or stratification is not the defining feature of caste”. He points out that the relative valuing of castes “is part of the relative valuing of social groups similar to the relative valuing of modern occupational groups, discipline-wise academic groups on university campuses, etc., all over the world. Just as these modern groups are not formed to seek relative value but that relative valuing happens after they are formed, castes too do not form for relative valuing, but that relative valuing happens after the caste formation”. Take for instance how much faculty earn in a research university in the US, and you may find that an assistant professor of finance, just out of graduate school, may be offered up to $250,000 dollars or more per year in salary compared to the $60,000 to $75,000 for a newly hired assistant professor of communication. Compare the $350,000 a year salary for a president of a regional university, with twenty to thirty years’ experience, and where s/he oversees a vast faculty/staff/student community with all of the pressures and anxieties involved in leading the institution to the $400,000 a year salary that a young radiologist is offered at a local hospital as s/he starts her/his career. This relative valuing of modern occupational groups, my friend argues is rooted in the relative value of an occupation, and in terms of caste/jaati ranking too we find similar valuation of different skill sets, availability of labor, demand for service, etc. Sure, when we as a people in occupational groups begin to identify with our group membership we begin to struggle for power, and in the jockeying for advantage we will see the emergence of social hierarchies, which if calcified over time or shaped by external developments — war, famine, natural calamity, or colonization — can result in discrimination against or oppression of certain groups, denial of rights to some, and even dehumanization. However, it is important that we do not misread or cherry-pick histories, categories, and worldviews when we look for the roots of social hierarchies, or when we try to respond to such oppression and/or discrimination.

Wilkerson acknowledges that race and caste are not co-equivalent but then asserts that they are not mutually exclusive. “They can and do coexist in the same culture and serve to reinforce each other. Race is what we can see, the physical traits that have been given arbitrary meaning and become shorthand for who a person is.” But where is the example from India where “race” and “caste” reinforce each other, and where Brahmins may be dark and swarthy and the Shudra or the Dalit “light skinned, tall, and handsome?” It is interesting too that she considers Nazism a caste system: indeed, we may ask, how did race and caste work in that dynamic? Was the German Jew swarthy, dark, and of a lower caste? Why is Wilkerson not considering the fact that with Nazism it was religion and religious identity that drove them to send Jews to the gas chambers? The Nazis, let us remember, were Christian, and that the Christian/Jew divide has been rancorous and deadly for a long time, just as the Muslim/Jew divide, and that it is all an Abrahamic blood-feud among family members. The Nazis used the “Hooked Cross” symbol to craft their “crooked Swastika” and we therefore now have social justice warriors or Christian bigots spray-painting hate messages on Hindu temple walls because they see a Swastika on the main door of the temple. The Germans having outlawed the use of the sacred Hindu/Buddhist/Jain Swastika symbol and now some US states too are considering outlawing the symbol. As Aravindan Neelakandan points out in a fascinating essay on the history of the hooked cross, Christians have succeeded in blaming the Hindu/Pagan for creating the symbol, claiming that the symbol was of “Aryan” origin, the “Aryans” invaded India, and that they created a race-based caste system in India. So, the Christian gets to have his hooked cross and beat the Hindu with a Swastika too. Wilkerson ignores the fact that it was also the Christians who brought slaves to America, and that most African Americans have embraced the religion of the slave-masters (and many have embraced Islam, the other Abrahamic religion where anti-Semitism hides in public view) but continues to look elsewhere for “casting” blame.

Wilkerson asserts that caste is “structure, ranking,” and that caste boundaries “… reinforce the fixed assignments based upon what people look like”. Well, if that is so, in my own, large, South Indian, Brahmin extended family we do not all look alike: I have cousins and uncles with thin-nostrils and hooked noses, and cousins and uncles who are darker skinned, have thicker lips, curly hair, and broad noses. We come in all shapes and sizes — from the big and bulky to the slim and dainty, and with light brown skin to very dark skin. We do not all look alike. Thus, Wilkerson’s use of the caste brush to paint Hinduism dark is both troubling and dangerous and is based on stereotypes and a superficial knowledge of the Indian reality.

Wilkerson points out to Dr. King’s visit to India in 1959, and how he was both peeved and flummoxed when he was introduced by a school principal in Kerala as a “fellow untouchable”. Of course, Kerala, the home of Indian communists, in 1959, had EMS Namboodiripad of the Communist Party of India as its Chief Minister, and Kerala politics involved the dicing and slicing of Hindu groups into various caste categories and riding those political divisions to electoral victory. That a school principal introduced Dr. King as a “fellow untouchable” would have been very much part of the clever, communist manipulation of Kerala’s political sentiments then, as now. If Wilkerson had done just a little bit of homework, she would have noted the intersection of communist politics with caste dynamics in the Kerala of those days. Sure, Dr. King would have known a little about the place he was in, and he too was a little sympathetic of communism: “As King rose to prominence he frequently had to defend himself against allegations of being a Communist, though his view that ‘Communism and Christianity are fundamentally incompatible’ did not change. Although sympathetic to communism’s core concern with social justice, King complained that with its ‘cold atheism wrapped in the garments of materialism, communism provides no place for God or Christ’.”

In another excerpt from the Wilkerson essay we read that the “Indian caste system” is “an infinitely more elaborate hierarchy” in which “the subcaste, or jati, to which a person was born established the occupation their family fulfilled, from cleaners of latrines to priests in the temples” but what she ignores is that the majority of people born into the “priestly” jaati/kula are not employed as priests. May be, in ancient times, when there were few of them, all the Brahmin males served as priests, but even then, the priest was expected to serve God/king/community by learning the sacred texts, maintaining the temple, and serving people. The priest, almost always, was expected not to pursue wealth, and Brahmins therefore were mostly poor, and were expected to go beg for food from the community they served. So, too, members of what are now called the Scheduled Castes are neither employed as cleaners of latrines or handlers of the dead. Indeed, that there is still a need for men to lower themselves into clogged drains filled with filth is not because of caste discrimination but because of the sloth, corruption, ineptitude of those who build those drains, and of the politicians who care little about modern infrastructure.

But, as other friends of mine have argued, there is indeed discrimination based on jati, and that “institutionalized socially acceptable discrimination carves out power, entitlements, opportunities, privileges, benefits, and treatment in a hierarchical manner,” that what matters is “the lived experiences of people as victims of racism and of caste discrimination…” and that “the entrenched discriminatory social behavior of caste is what is visible and experienced” just like in racial discrimination. If that is so, others point out that “…social stratification, hierarchy or ranking as an observable social behavior also exist in non-caste social groups such as modern occupational groups, disciplinary academic groups on the university campuses, etc., and therefore the causal relation between the defining features of a caste system and social stratification, hierarchy, or ranking must be a wrong assumption”. They correctly argue that when the identification of causal relationship between a problem and its root cause is wrongly done, then whatever solutions we find or propose can and does go wrong. We have seen this in India where lawmakers have been over-generous in “reserving” huge percentages of seats to the Scheduled Castes, the Backward Castes, and the Other Backward Castes in schools, colleges, universities, and a similar large percentage of reservation of jobs in government service — from doctors and engineers to the lowly sanitation worker — with deleterious results.

Social hierarchy is a universal reality and even socialist and communist countries that have sought to level the playing field for all have not been able to get rid of it: for what Mao and his comrades, and Stalin and his communist apparatchiks enjoyed in terms of power and privilege are what we also now see also being enjoyed in North Korea by Kim Jong-Un and his team of hysterical acolytes, or what we saw in the Indian state of West Bengal for thirty years when the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M) ruled that state. West Bengal’s Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, was fond of his Scotch, sipping a generous dose every evening, and taking annual vacations to the United Kingdom, even as Bengalis suffered unemployment, wretched public service, and the flight of industry because of his CPI (M) policies. The Fabian Socialist Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, was not shy about seeking, demanding, and enjoying state power and the privileges that came with it. Durga Das’ book, “India from Curzon to Nehru & After” offers some rich details to those curious about Nehru’s socialist pretensions and promises, and we see to this day how the Nehruvian acolytes claim membership to the elite social club of “progressives” in India, denying power and privilege to those whose political affiliations are different or those who lack a command over the English language. Caste has morphed and taken different shapes in India, and Wilkerson and those who read her sympathetically fail to take note of the same.

Hindus of yore, not just the modern ones, have over centuries acknowledged the ills of social hierarchy, and have waged battles, both philosophical and practical. There are simply too many of those social reformers to list them all here, but without exaggerating we can claim that in every age, and across every “caste/jaati” group in India, we have seen emerge a king or a village chief, or the head of a religious school or a mendicant who railed against humans acting inhumanely against another based on their group identity. If so, then why did “caste/jaati” not die out if there was social opposition to it? Because jaati has always constituted social capital, and members of a jaati group intermarried, relied on one another for support, learned skills from the expert group members, and held on to their trade skills that offered them both a livelihood and opportunities to excel and influence society. As to the present state of “jaati/kula” in India an astute friend pointed out that “the real reason why caste is dying too slowly in India is due to its ‘positives,’ including kinship and social capital,” which was so even in the past. He argues that social capital will become irrelevant once the Indian state grows to a size where it can provide a basic standard of living to everybody. This friend also made the very important point that in no other country, except India, there has been “a multi-generational, open-ended system of affirmative action to remedy the wrong” arising out of past discrimination. But caste continues to play a major role in India not because Brahmins want to discriminate against everyone, and everyone loves to discriminate against each other, but because India’s first-past-the-post election system makes castes relevant as a way of political mobilization, my friend argues, and because the wrong/socialist economic policies adopted by “socialist” governments curtailed growth and jobs for nearly five decades. We may add that caste dynamics are also kept alive by India’s many activist groups whose livelihood depends on the generous grants from the Indian state, global corporations, church groups, and international agencies. Furthermore, global Christian and Muslim groups have a vested interest in keeping caste antagonisms alive in the hope that Hindus can be “saved” and India could be Balkanized.

Wilkerson’s NYT essay does not allude to any of the aspects of the Indian “caste system” listed above, and so for those interested in challenging if not debunking the claims made about India’s “caste system,” we can point out to a two-part article here and here, and a review of the book, “The Western Foundations of the Caste System,” here.

In closing, we may point out that Wilkerson, accidentally, reveals her own social privilege when she visits India, and her description of her first visit to India in 2018 reveals her position in the global hierarchy of nations. This is what she observes of Indian “Third World” reality:

“My flight to India landed in a gray veil that hid the terminal and its tower at the international airport in Delhi. It was January 2018, my first moments on the subcontinent. The pilot searched for a jetway through the drapery of mist. It was 2 in the morning, and it was as if we had landed in a steam kettle, were still airborne in a cloud, the night air pressing against cabin windows, and we could see nothing of the ground.… The pollution was a shroud at first to seeing India as it truly was…. At daybreak, the sun pushed through the haze, and once I connected with my hosts, I raced along with them to cross an intersection, an open stretch of asphalt with cars hurtling in every direction with no lanes or speed limits… I saw the wayside altars and mushroom temples with their garlands and silk flowers to the Hindu deities at the base of the sacred fig trees. There, commuters can pause for reflection as they head to work or an exam or a doctor’s visit. The sidewalk shrines seemed exotic to me….”

If anyone else were to write this we would be accusing them of exoticizing India and/or being racist. Wilkerson gets away without any protests from the editors of The New York Times.

Wilkerson’s latest essay and book is therefore just a new addition to the old Western oeuvre on the “Hindu caste system”. As Ronald Inden, a perceptive observer and critic of Western Indology notes:

“Indological discourse… holds (or simply assumes) that the essence of Indian civilization is just the opposite of the West’s. It is the irrational (but rationalizable) institution of ‘caste’ and the Indological religion that accompanies it, Hinduism. Human agency in India is displaced by Indological discourse not onto a reified State or Market but onto a substantialized Caste. This has entailed several consequences for the Indological construction of India. It has necessitated the wholesale dismissal of Indian political institutions…. To give this construct of India credibility, the depiction of Indian thought as inherently symbolic and mythical rather than rational and logical has also been required. Finally, it has been necessary for Brahmanism or Hinduism, the religion considered to be the justification of caste, to be characterized as essentially idealistic (i.e., apolitical). Caste, conceived in this way as India’s essential institution, has been both the cause and effect of India’s low level of political and economic ‘development’ and of its repeated failure to prevent its conquest by outsiders. Given this, it was only ‘natural’ for European scholars, traders, and administrators to appropriate the power of Indians (not only the ‘masses’, but also the ‘elite’) to act for themselves. This they have done since the formation of Indological discourse made it possible. Despite India’s acquisition of formal political independence, it has still not regained the power to know its own past and present apart from that discourse. The fixation on caste as the essence of India has had still another effect. It has committed Indology, largely descended from British empiricism and utilitarianism, to a curious and contradictory mixture of societalism, in which Indian actions are attributed to social groups — caste, village, linguistic region, religion, and joint family — because there are no individuals in India, and individualism, in which Indians’ acts are attributed to bad motives…” (“Orientalist Constructions of India”, Modern Asian Studies, 1986, 20–3, p. 402–403).

Alas, copies of Wilkerson’s book have already reached the CEOs, the mayors, the academics, and whoever else that Oprah Winfrey (we may wonder if she in fact reads the books she recommends or just that she pitches whatever her cabal tells her to) thought fit to send them to, and the review of her book “Caste” now tops and crowds out a Google search for “caste”. The book will win a Pulitzer Prize no doubt, hundreds of academics will prescribe the book to their students, thousands of Indian students will get further deracinated from their Hindu families, and millions who buy copies of the book will go to sleep thinking that they have figured out racism, understand “caste,” and found a solution to America’s social inequities. Reviews of the book by the hundreds of readers on the Amazon site will confirm this — both the ignorance and spite of readers and how that has been encouraged and stoked.

Meanwhile, from someone who has read Wilkerson’s book, we now know that the book is equally mischievous, poorly sourced, reliant on the works/words of maniacal writers like VT Rajshekar, and offering cherry-picked examples of either discrimination or of denial of so-called caste identities. Wilkerson’s next book could be titled “Karma” and tell us how it is her karma to be rich and famous in this life!

This article has been republished. The original article can be read here.

Photo Credits: Greelane

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.