Was Indus Valley civilization Dravidian?

Introduction

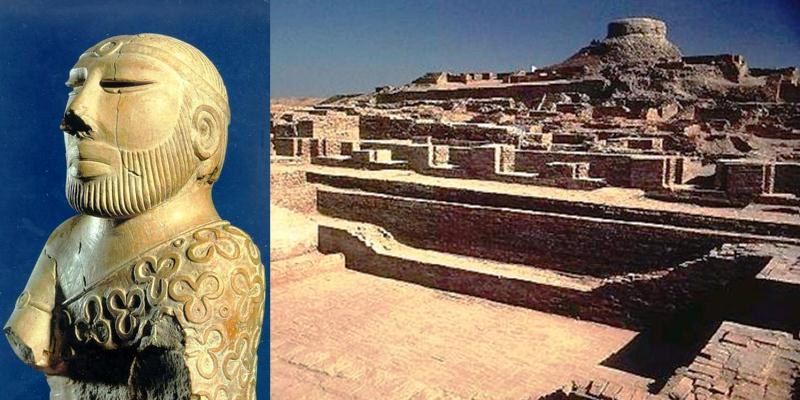

The Sarasvati-Sindhu/Indus Valley or Harappan civilization is the earliest discovered civilization in the Indian subcontinent. The writing system of the Indus civilization is not yet properly deciphered and many Indologists and authors have tried to associate the underlying language of the Indus script to various language families as per their hypotheses. One of the widely popular theories is that the Indus script was used to write the early Dravidian language that was supposedly spoken by the Harappans. They state that Harappans were Dravidian speakers and the Sanskritic Indo-Aryan speakers came into Harappan regions and settled there later when the civilization collapsed. At the same time, the Dravidians of Harappan regions moved into southern India where Dravidian languages are popularly spoken today. Dravidianists further claim that the Harappan civilization was their pre-Vedic casteless egalitarian utopia and the Vedic Aryans who came later imposed the oppressive caste system on the native Dravidians. This claim is also utilized by Christian missionaries for demonizing the upper caste Hindus who are said to be the descendants of the intruding Aryans.

There are many issues with this view, and this article analyses the claims of Indologists and Dravidologists who state that Harappans were pre-Vedic Dravidians.

Geographical Distance

The southern-most Harappan site is in Daimabad, northern Maharashtra, and we do not have any traces of Harappan sites in deep southern India. If Harappans were Dravidians, they would have obviously left traces of Harappan sites in deep southern India where they later settled. But this is not the case. Also late/post-urban Harappan culture of northern India such as Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP)/Copper Hoards and Painted Grey Ware (PGW) culture, etc. are restricted to northern India only. We do not find any traces of them in the south. Even Cemetery H culture that is now considered as late Harappan [1] is also restricted to northern India.

We do not have any traces of the movement of Harappans into southern India. OCP culture and PGW culture do show an overlap with late Harappan culture in some sites [2], but still, they only give testimony to a movement from Harappan regions towards Gangetic regions, which was later the home of late or post Vedic civilization during the early Iron age, and not to southernmost India.

Vedic heritage of earliest attested Dravidians

The oldest Dravidian literature is the Sangam Tamil corpus, and the period it belongs to is known as the Sangam age (starting from 5-4th century BCE approx.), which is the earliest historically attested era of Tamils. There is more than a 1000-year gap between the decline of the Harappan urban centres and the Sangam age texts. But many Indologists and others who put forward the Dravidian-Harappan theory make use of Sangam age texts to come to the conclusion that Harappans were Dravidians. But in reality, if we go through the Sangam age corpus, we see a thoroughly Vedic Hinduized Tamil society. The Pandyan kings such as Palyagasalai Muthukudumi Peruvazhuthi [3], Chola Rajasuyam Vetta Perunarkilli [4], etc. got their names after they performed Vedic Yajnas. Moreover, early Tamil coinage and script were also the same as that of northern India; they utilized punch-marked coins and the Brahmi script. The coinage also includes symbols such as Srivatsa, Nandipada, Swastika, dhvaja, etc, all of which are common Hindu symbols in northern coins as well. Thus, it is clear that Sangam age Tamil society was already Vedicized, and we do not need to search for any non-Vedic past of the Tamils or early Dravidians through Sangam age texts, which are the earliest Tamil (and Dravidian) texts available. Sangam age texts also have no mention of any older Dravidian homeland in the Harappan regions. Core regions of Sangam age Tamilakam were only modern Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Although the texts also mention northern regions such as the Himalayas, it is also said in the Sangam age texts that the Himalayas were inhabited by ‘Ariyar’ [5], i.e. northerners from the ancient Aryavarta region. Even the Tamil word for the Himalayas, Imayam, is a loan word from the Indo-Aryan word Himalaya. Thus, it is clear that Sangam age texts betray no traces of any northern homeland of Dravidian Tamils. It is, however, true that Velir clans of Sangam age Tamilakam traced origins to the north, in Shri Krishna’s Dwaraka puri Thuvarai, as mentioned in Purananuru [6]. The inscriptions also mention them as descendants of the Vedic Yadava clan [7]. Hence, they can only be seen as early migrants into Tamilakam who brought the Vedic culture along with them to the south and not as any Dravidian migration from Harappan sites to south India.

The Brahui Issue

Many authors highlight the Dravidian speaking Brahui tribe that inhabits the modern region of Balochistan in Pakistan and is close to Indus valley. One of the arguments is that the Brahuis may represent the remnants of the early Dravidian inhabitants of the Indus valley who were later Aryanized or driven off. But, there are also people who argue that the Brahuis were later medieval migrants to the north from Central India. This is possible because only around 15% of Brahui vocabulary contains Dravidian words [8] and it also does not contain any early Indo-Aryan or early Iranian loan words. So, it means that the Brahuis were not present in the Balochistan region during the early Indo-Aryan Vedic and Old Iranian period. The oldest layer of loan words in Brahui language is from later languages such as Balochi, Sindhi, etc. that evolved during the medieval era. Thus, this could indicate that Brahui migration towards the north would have happened only during medieval times. Also, we have late arrivals of Dravidian languages such as Kurukh in far northern regions like Nepal. Most authors agree that the Kurukh had its original seat in central India and migrated to the north later. Similar would be the case of Brahui migrants.

Dravidian influences in Sanskrit

Another argument is that the early Vedic texts such as the Rig Veda contain many Dravidian influences such as loan words from Dravidian languages and features such as retroflexes that are not found in most other Indo-European languages. Thus, the Dravidians were present in Harappan regions before the Indo-Aryan speakers came in during the post-Harappan era and borrowed these features from the remaining population of Dravidian speakers in Harappan regions. First of all, there is nothing to prove that these influences happened during or after the Harappan period. Also, it is agreed by Indologists that so-called loan words were not that prominent in early Vedic Sanskrit since 96% of the Vedic lexicon is purely Indo-European in nature [9]. The loan words increased only in the later Sanskrit literature. Hence, we can view that an earlier proto form of Vedic Sanskrit did not have these loan words as it was located in far north-western India. And by the time Sanskrit evolved, it acquired these loan words and other features through long mutual contacts with other language families like early Dravidian, which could have located further south from core Vedic regions as the Vedic culture (which is to be identified with Harappan culture) spread throughout other regions from the north-west.

Dravidian Place names in the North

Along similar lines, many authors also argue that there exist places with non-Sanskrit names in northern India. This may be true, but we should remember that modern names cannot be compared with ancient names. For example, there have been claims that the -kot suffix in many northern Indian place names is actually derived from kottai, the Dravidian term for fort. But places with -kot in their names would have had an earlier more ancient name, like in the case of Sialkot in Punjab which was known as Sakala in ancient times. Other names such as Faridkot, Sherkot, etc. are only medieval names after Muslim expansions into India. It is also possible that places got their Dravidian-like names via the transmission of Dravidian words into the north by the contacts between Indo-Aryan and Dravidian groups in further south. As noted above, there could have been mutual interactions between the Indo-Aryans and Dravidians since ancient times when Vedic culture began to expand.

Apart from this, in historical times, there had been many movements from Dravidian speaking regions into the north. For example, southern dynasties such as the Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, etc. expanded all the way into parts of northern India. Even earlier, the Andhra Satavahanas who conquered many regions of the north were also from the south, and even though they used Prakrit predominately in their inscriptions, their empire would have still hosted a local Dravidian speaking population of the Andhra region which would have expanded along with the expansion of the empire. So, some of the places in the north might have got new Dravidian names during southern movements such as these. The Brahui issue detailed above can also be explained in this way along with the case of Kurukh migration into northern regions. Perhaps there were many such movements and expansions from the south to the north in ancient times; we will never know.

Indus signs from the South

Yet another argument comes from the claims of various supposed findings of signs related to the Indus script being discovered in southern India. Most of these isolated claims of Indus script-like signs come from supposed graffiti found in megalithic cultures. Such signs are found in northern India as well. For example, this seal from the ancient city of Vaishali [10] in north India contains graffiti similar to the Indus script [11]:

Obviously, by the time Vaishali was built, the region was inhabited by Indo-Aryans. Thus, it is clear that Indo-Aryans also used such graffiti. Even if these isolated graffiti turn out to be related to the Indus signs, that does not mean that the underlying language of these signs is Dravidian. If we identify the Indus language as Indo-Aryan, it could only mean that these signs travelled south during the spread of Indo-Aryans into south India which led to the Vedicization of the region. Also, it is to be noted that we have cases of many Indus scripts showing up in many other regions such as the Middle East, Central Asia, and Iran. These are obviously from distant contacts, thus, similar would have been the case of these supposed isolated southern Indus-like signs.

Conclusion

From all these points, we can note that the argument for Dravidian ownership of Sarasvati-Sindhu/Indus or Harappan civilization holds little weight. As noted above, it could be possible that early Dravidians lived south of Vindhya mountain ranges, in the northern Deccan, or perhaps even in Harappan border regions to the south, and they came in contact with the Vedic people from further north, especially modern Punjab-Haryana and parts of Uttar Pradesh, while the Vedic culture expanded, and they both had mutual interactions and transfer of cultural traits and motifs. While the Dravidian terms got into Sanskrit (if at all), the early Dravidians adopted Vedic culture in the process, and hence the regions of Deccan predominantly had usage of Indo-Aryan Prakrit since earliest recorded times, and the earliest Dravidian literature, the Tamil Sangam literature, already reflects a society following Vedic culture as its mainstream culture.

References:

[1] The Harappa Project 1986-1989: New Investigation at an Ancient Indus City by George F. Dales and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer

[2] A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century by Upinder Singh

[3] Purananuru 6

[4] Purananuru 16

[5] Pathitruppathu 11

[6] Purananuru 201

[7] Trade, Ideology, and Urbanization: South India 300 BC to AD 1300 by R. Champakalakshmi

[8] Encyclopaedia Iranica on Brahui http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/brahui

[9] Linguistic Evidence for Cultural Exchange in Prehistoric Western Central Asia by Michael Witzel

[10] Vaisali excavations, 1958-1962, by B. P. Sinha, and Sita Ram Roy

[11] Iravatham Mahadevan as cited in The Lost River: On The Trail of the Sarasvati, by Michel Danino

Featured Image: Google Search

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.