Who is disrobing Draupadi?

The first edition of Bharat Shakti Pondy Litfest 2018, Puducherry was a special one because it was the first of its kind of festival bringing together some great minds of India and abroad discussing our rich heritage and ideas to understand what Bharat Shakti is. But, personally it was even more special because I got to be a participant for the first time on a panel discussing ‘Identity & Empowerment: Where is the Indian woman today?’ The panel started with exploring what does it mean to be a woman and who is truly a Shakti? Do we really understand what it means to be a woman? Then almost predictably, the discussion turned to Draupadi, the incident of her disrobement, the fact that she was a wife to the Pandava brothers and following that many points were raised defending her, how to raise boys and girls in today’s context etc. Much after the panel discussion, I was still reflecting on it and was a bit uncomfortable with the way Draupadi or even Sita for that matter are discussed in today’s discourse.

Are they mentioned by people to try and speak about their reality? Why is Draupadi, an archetypal Shakti being constantly referred to in today’s context? What are our issues of femininity or oppression that we are unable to look at it straight in the eyes? What is the context today that is triggering the reference of a text like Mahabharata? How do we use stories of the Mahabharata to compare today’s reality and are we then casting aspersion on an entire meaning of a cultural heritage of a group?

Of course, I could not get my head around these questions on my own, so I turned to Raghu Ananthanarayanan, a yogi coach who has been conducting numerous Mahabharata explorations/immersion labs to delve deep into the psyche of the being using the puranas.

Gayatri: Raghu, I am very curious to understand the methodology people use the puranas to dissect their realities or context.

Raghu: First you need to understand who are these people? And what motivates them to interpret the stories the way they do? And who are they speaking about?

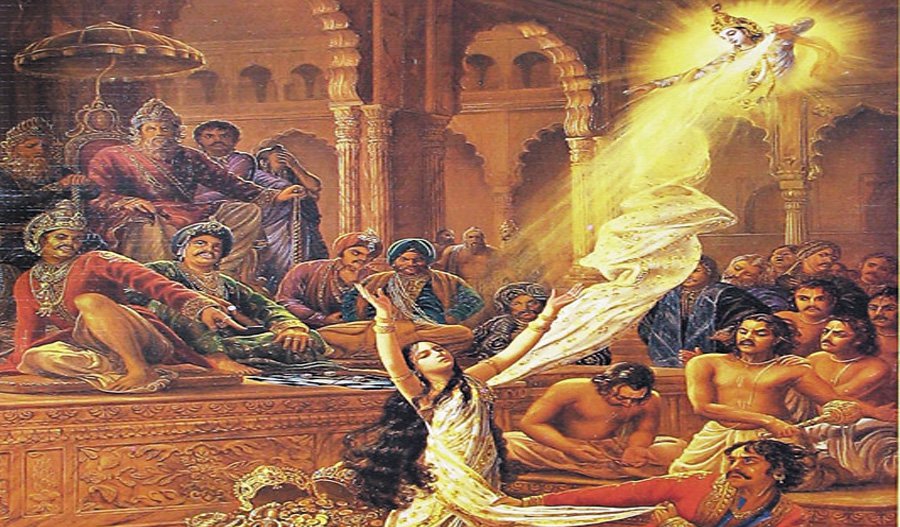

Puranic stories can be used as self-reflective mirrors. The recounting and re-telling then says a lot about the story teller, their lives/themselves and their context. So, when I look at say Draupadi from this framework, I can see her strength and her accomplishments; by the way she was the holder of the treasury! In the court that tried to rob her dignity; she argued her case very competently and the elders had no answers. It was only when she accepted her vulnerability fully and said to the oppressor “you can neither fathom nor touch my inner connection with the divine”. Everyone in the court including her husband’s hung their head down in shame and guilt. For me this is the story of an empowered woman, not that of a victim. One has heard the story of Guru Gobind Singh before he was beheaded saying “you can have my head, but not my Self”. Draupadi made the same statement and Dusshasana was humiliated!

In my work with people I see a pattern: the victim narrative is often an unchanging one to which the person keeps returning to and regurgitating old stories of hurt, oppression and humiliation. Some of it is real, and some of it embellished with one’s own nightmarish fantasy. Unfortunately, the strength that made them live through to tell the story gets buried under helpless rage. The real empowered narrative speaks about an awakening of inner strength and heroism; one of discovering an insight and inner light. These stories enable the so-called victim to rise above the violence, heal oneself and the other. Nelson Mandela also spoke eloquently about this possibility.

Gayatri: Then the choice of my interpretation squarely on me and reflects my own inner state. This is liberating but places a great responsibility on me and of course it is very tough to do so.

Raghu: See, one can use a puranic stories to understand the context of the time gone by. The Mahabharata speaks of a time when both polygamy and polyandry were possible, and it speaks about the ethics of conduct where Draupadi defines boundaries. She is the one who confronts her husbands with her head held high when their resolve weakens on many occassions. It also speaks about the time when birth defined access to power and resources, one can go on about many such instances. However, one cannot apply today’s morality or ethnics to pass judgement on those days! Using this lens to interpret the old, and then using that interpretation of a constructed past to decry or shame the whole cultural reality of the present is meaningless and probably motivated by self-loathing. In my understanding the current spate of rapes has more to do with the culture shock of a villager confronting modernity, the loss of community, the closed doors to discuss healthy relationships, the easy availability of porn on the hand phone, the constant portrayal of hyper masculinity in almost every advertisement and so on. It is strange that the lens of culture is not applied uniformly. For e.g. in the US there was a recent report that said that about 1 in 4 college women in US can be expected to be raped. Yet I don’t see a discourse wherein the entire culture or its symbols are brought forward to dissect the issue unlike here in India.

Gayatri: I see what you mean. Our culture allows many views of a reality to be put forth, the play of the Gods is often depicted farcically in folk theatre. The boundaries are clear and neither the audience nor the actors are conflating the reality. They use it to highlight issues.

Raghu: Yes, understand that there have been many commentaries on the way allegory and myth can be used to initiate a spiritual journey. Most famous among them is Joseph Campbell, who clearly speaks about what happens to a culture when metaphors like Adam and Eve, Draupadi or Sita are reduced to mere human figures? An unsolvable problem is created when metaphors are taken quite literally because because that leads to directing us to look outward at mundane reality, but they ought to point us inwards into a space beyond words. A simple example is with respect to nudity; in every culture we say that “we stand naked before God” and in the Draupadi vastraharana episode a clear metaphorical meaning is being given to what happened. It is a metaphor of a failure; failure of the society or individual in the context to stand up and act from their agency; the failure of the person who takes advantage of a certain context to become exploitative. The impact of such acts is felt by the vulnerable and voiceless in any society. When these impacted people find an inner path to a divine energy at that point in time, they go beyond their victimhood to become empowered to bring about a great social change. Gandhiji called it satyagraha.

Gayatri: Hmmm…that makes sense. Then Krishna and his play with the Gopika is also a metaphor of completely dissolving one’s ego and merging with the Godhead.

So, can you elaborate more on what are these purana written for?

Raghu: Puranas were written as metaphors and the reason for deconstructing the text is to help people understand the meta-meaning behind them. The Mahabharata is not a story of successes, it is a story of failure! There are countless situations where if the “elders” or the “heroes” had acted from a Dharmic ground there would have been no war. To illustrate, Karna was not given the due recognition for his great capability. His birth and a distorted idea of dharma was used by Drona and Bhishma to reinforce an unjust social reality. If one goes even deeper, all the characters of the Mahabharata are archetypal figures, they are parts of one’s inner drama.The beauty of these texts is that it is supposed to help you find a deeper meaning, understand what is dharmic or adhArmic in very simple yet profound ways like in Indian traditional theatre like Koothu or even the Yakshagaana bomaiattam puppetry. The character names are itself metaphorical; like Duryodhana or Dushasana; du clearly denotes negative meanings, no one is named Duryodhana, he was named Suyodhana and became Duryodhana when envy took hold of him. Yudhishthira as a name clearly conveys stability among chaos and war. Draupadi is an essential principle of prakrti and she enables prakrti to act or provides a sense of order. If I take it further, Draupadi thus needs five husbands or ways in which prakrti manifests through the senses. The central space that holds the Panadavas together is Draupadi i.e. the essence of dravya or matter. The lives of the Pandavas actually tell me that if I do not understand all the aspects of myself, then in what way violence can take hold of me or if I do not respect femininity, then how would it lead to destruction.

Gayatri: If these were so profound, then how did these traditions and ways get lost?

Raghu: My speculation is that either directly or indirectly, people who could interpret these things are being projected in a negative light. Like a wise traditionalist who truly understands these texts in a context is discredited and is seen as irrelevant, old etc. The voices of people who do not practice or have not looked at it from an inside out perspective has become legitimate. If this voice is used to enable a social enlivenment, then it is fine but if this voice sets upon itself a task of shaming or provoking guilt then we have a problem. If I had not studied these texts in the context of my own personal sadhana with Yogacharya Krishnamacharya, then I would have also got caught in these superficial frameworks that is being talked and taught. We need teachers and guides who can help direct us inwards using these texts.

Gayatri: I remember some remarks about Draupadi being reduced to something very superficial like ‘having to sleep with 5 men’ and it always left a sense of anger against the context. I wonder why it left me so disturbed?

Raghu: The way the stories of Draupadi and Sita are being used nowadays is for generating anger or divisiveness rather than asking questions that enable self-reflection. Instead of looking at my own struggle, it becomes a mere ‘you vs me’ or ‘us vs them’ kind of discourse, which is what we ought to avoid. I think the discourse is coming from an entrenched victim location wherein you project the shame and guilt on the other. It has nothing to with being a man or a woman because archetypes are beyond gender. These stories could and should help you examine your own narratives. There are many stories in the Mahabharata wherein the Princes suffered for the way they lived for 13 years in the jungle and how hard they tried to make Draupadi’s life meaningful etc. So, it is a case of an entire clan or context who are going through trauma rather than an individual. Draupadi is only an agent in one specific story, Yudhishthira’s trauma of losing his entire Kingdom in a game of dice is equally traumatic like Draupadi’s vastrAharaNa. All of this is part of the trauma the entire family or society goes through. Draupadi is not happening to some else 3000/4000 years back, it is my own inner energy, thus it becomes useful to delve deeper for the sake of my own growth.

In Ramayana also, when a person needs come to terms with his or her own power he/she discovers the order and beauty of ramyam within. Until I bring order within, I am a Ravana, I am incapable of acting dharmically. But if I do not encounter my Ravana I cannot realize my potential as Rama. Similarly, when a woman encounters a flamboyant or macho guy she has to find the inner core that answers the question ‘what does she really value in a man?’ Is it an inner anchored human being, dignified like Rama or is she getting carried away by man who is all macho? Metaphorically the Ramayana is a confrontation by both Rama and Sita with their counterparts, discovering who they are and each other also. Thus, by looking at it in this way, it is a beautiful allegorical story interspersed with trials by fire (literally!)

Gayatri: How do these stories illustrate society paying a price?

Raghu: If a just King is thrown out and people like Bhishma who were supposed to uphold the justice until the right King ascends the throne was silenced by a Dushasana or Duryodhana, who then go on to rule the society then the whole of society and even nature pays a price. They will continuously exploit people and nature, that scene of disrobement is a failure of people who were supposed to protect and uphold justice. We see the failure of the state and our unsustainable ways of living all around us today, isn’t it a collective failure and all of us being part of the problem?

Gayatri: Does Draupadi have to feel as a failure or guilty?

Raghu: Not at all, in fact the only person who does not fail is Draupadi. She does not have to feel ashamed about anything and that is why Krishna comes to her rescue. She stands there with her head held high, blameless and saying ‘Yes, I am naked, and God will come to my rescue’. In fact, she triggers the feeling of shame and nakedness in everybody else wherein each of them has failed in their tests of upholding dharma. Draupadi has not lost anything.

Gayatri: Then why do we have such a difficulty to portray this confidence and victory?

Raghu: Well, when a woman who is victimized feels ashamed then it is the whole society that is projecting their inability to own up to the shame on to the person. Of course, it is also very tough for this person to come out of their beloved victimhood say ‘No, this violence does not belong to me and it is an exposure of the violence and impotence of everyone else.’

Gayatri: I come back to the main question, who is disrobing Draupadi and why?

Raghu: That is what I am asking too; in every discourse today, everyone is disrobing Draupadi repeatedly without understanding how they are part of the problem. A disrobed Draupadi is a dignified beautiful person and not a victim anymore because she refuses to accept that whole act as her misfortune. So long as you are fighting, reacting or resisting, you are still part of the whole problem. The moment you step out of the cycle of violence and violation, the violator must see their ugliness. The one who is being disrobed is not Draupadi but all the other people around sitting in the sabha including the women there. So again I repeat that it is a societal shame and failure; and not Draupadi’s doing or victimhood. The repeated use of the metaphor that ‘Draupadi is the victim’ is the disrobement. Now, the rest is for you to ponder upon.

Featured Image: Amar Ujala