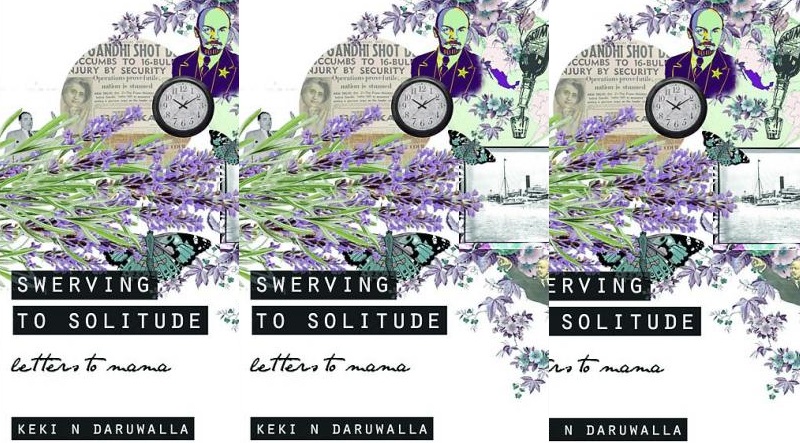

Book Review- Keki Daruwalla’s Swerving to Solitude: Letters to Mama

Acclaimed poet Keki Daruwalla’s interest in history of remote past as also not so old is well known. It is this that has probably drawn him into novel writing even as his stories were always popular. He likes to juxtapose the political with the personal in a multi-narrative novel. His first novel For Pepper and Christ dealt with the early sea voyages to India by Europeans. Whereas his second novel Ancestral Affairs focussed, apart from the love life of a youth, on the period around Independence and the simultaneous Partition of the country.

Swerving to Solitude: Letters to Mama takes up the history of India from the period of Emergency (1975) to Operation Bluestar (1984). The locale shifts from Delhi and Lucknow in India to Canada, US and Mexico, placing action during the period of the First World War. The story is told in the form of a monologue of a young, married woman Seema though she addresses it to her dead mother! Obviously, there is no response, so it is safe to take it as a diary with a difference.

Seema, wife of Nishant, an IAS officer, is a budding journalist with the Lucknow Chronicle. She is an outgoing, outspoken, Left-leaning intellectual type. Her friends Shilpa, Rabia and Zaira make a mirthful company and in their private conversations make fun of Indira Gandhi and her actions. Seema’s rebellious instinct shows itself when she has a 2-night stint in jail (cooler) for slapping a policeman who had hit an innocent person in the street while he was watching the sealing of a Jan Sangh cadre Shambhu Nath Pandey’s shop. Alfred Hemmings (Alfie), known to her through her friend Shilpa, is a foreign journalist working in India for the Christian Science Monitor and has sympathy for the opposition parties. He later persuades Seema to take a packet containing money to Pandey, whch action involves her in a court battle compounded by police highhandedness.

The writer is able to bring alive the Emergency days by describing how the opposition parties and their sympathizers worked under that reign of terror; how even a lowly maid is picked up because her daughter, in a psychic state of mind, predicted jail for Indira Gandhi; how the journalist Alfie goes missing. It was the time when you became a celebrity if you were on the side of the government, like that sweet seller Anupam became.

We do read about people being rounded up for vasectomy operation during the Emergency period. How some of them run out of the operation van even as a fellow is undressed makes for a funny, even though, grim reminder of those black days. Daruwalla, a retired senior government official having worked with the Prime Minister’s Office besides holding other important charges in the police department under the Home Ministry is witness to a lot and has the status of an insider but he has chosen to don the attire of an artist rather than that of a whistle-blower. The novel also talks about the post-Emergency period when Indira was not in power but what was there was the rampant corruption.

Structurally, the section captioned “Mother’s Journal (1910-1920)” seems dispensable, as it deals with the history of Seema’s parents and grandparents, but the personal history is intertwined with the history of the immigrants in the US, Canada and Mexico during the heady days of India’s freedom movement coinciding with the eruption and ending of the First World War. The tenuous link that this section has with the main narrative appears to be to locate Seema’s revolutionary DNA in her family genes. Her mother worked as Secretary to the Communist leader M.N Roy while in Mexico. The novel dabbles in international politics, what with spies like Mata Hari thrown in. For Roy, however, the Communist movement mattered more at the world level rather than in the confined space of India as is evident from his comment to Ramos: “I thought the good of mankind, which means the proletariat, is a better cause than the good only of Indians.”

Daruwalla’s aversion to present-day BJP leadership is evident in the form of a forecast from the minor character Elham, who, true to her name, has intuition or dreams which foretell the fate of Indira Gandhi. The latter’s loss at hustings and her death are forecast by her leading to threat to her own life too. The novel concludes with one such dream which she is coaxed to share with Seema: “A huge man riding on a wild donkey, with a barcha in his hand, a barcha with three spearheads, with lots of followers also on wild asses, will be riding towards Delhi” (234). Here, the present Prime Minister is portrayed as leading a crowd of trident-wielding people on ass-backs, but Daruwalla desists from naming Narendra Modi. That is a fictionist’s artistic privilege to keep the veil on and yet make intent clear!

Daruwalla’s characteristic wit is reflected all over the novel: “The past has a habit of digging its way up like a rodent sometimes.” A country becomes backward because of backward beliefs which sit on our shoulders like Baital on the shoulders of Vikramaditya.” Daruwalla takes a dig at the Parsi community too. They used to be fighters once, he says, now they only fight in courts!

Daruwalla’s innovative style in making the protagonist address her dead mother has the advantage of her being truthful in a uniquely endearing way. Seema becomes a child when she writes the narrative for her mother: “The police call it embossing, Mama. So does the army. Ever heard the term?” The language of the novel is befittingly colloquial – something that comes as a surprise for readers of Daruwalla’s short stories and even many poems couched in rather difficult English. On the whole, the novel is an artistic tour de force though one would have liked the writer to divulge more of the back-stage manoeuvrings and machinations of the Emergency era.