Hindu law and jurisprudence: a Primer

This piece is intended to demonstrate that Hindu or Brahmanic law is rooted in popular convention and practice.

While it is a high textual tradition, it incorporates divergent folk tradition. Hindu law was never envisaged as a fixed legal code valid for all time and place. Key provisions such as divorce and inheritance were revised depending on region, community and the ethos of the times. That said, a coherent and over-arching theoretical framework exists, one that can be recognized for its distinct features such as social corporatism. Hindu law influenced the development of legal thought in late classical and early medieval Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar and Thailand, not to mention the Jaffna Kingdom of Tamil Sri Lanka.

The Brahmanic legal tradition demarcated a specific social framework. The principle of social interconnectedness contributed to a corporatist, albeit segmented social framework that had endured over the centuries.

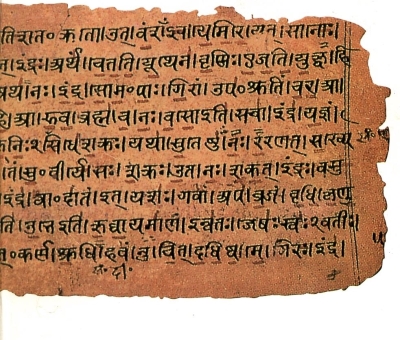

The Dharma Shastras (100 CE) are the pre-eminent Hindu legal texts written in Sanskrit, excerpts of which were translated into the early Javanese and Khmer languages. Niti, i.e. justice, is based on Dharma, i.e. the moral law in these works. The term Dharma is derived from the root word dhr, i.e. that which supports or sustains. The expression has a range of meanings. It signifies both counsel of general prudence as well as the highest virtue conducive to human welfare.

The concept of Dharma represents a comprehensive and consolidating view of life. It however also caters to individual contexts. This contextual specificity of Dharma permits a continuous adaptation to changing social situations and times. It remains nonetheless a broad theoretical framework which transcends the immediate despite a sensitivity to changing social contexts.

Hindu jurisprudence developed as the civilization incorporated peoples wholesale be it in South East Asia, the Himalayan regions, India’s pre-colonial North East and the deep south. These newly inducted communities introduced newer practices. The legal framework adapted to historical, political, economic and social changes[i]. Medieval commentators re-interpreted legal statutes to keep pace with newer contexts. Legal codes were revised due to the influence of regional custom. Numerous interpolations, recasts and additions are seen in the Manu Samhita itself[ii]. Hindu law is a complex and dynamic code open to changing needs and imperatives. However, its coherent theoretical parameters reconcile evolving circumstances with the basic principles of law.

The principles of Hindu jurisprudence are not confined to the texts in Sanskrit. Manu attests that custom is the foremost basis of jurisprudence. Customary law delimits Brahmanic legal theory. And customs differ according to districts, towns, castes, guilds and corporations[iii]. Traditional usage prevalent in the community is upheld in the Hindu tradition over the letter of the law found in the texts. Manu asserts that a centralizing monarch is obliged to protect local practices. He asserts the precedence of provincial custom. Hindu law is therefore not an elitist textual inheritance frozen in time and divorced from folk convention. Brahmanic legal theoreticians reconciled abstract principle and conflicting practice in formulating a code of law.

Unwritten tradition continued to supersede textual statutes in colonial India. This was so in the Bombay presidency, the Punjab and Awadh. Custom shared equal place with the written law in the Madras presidency and in the central provinces[iv]. Hindu jurisprudence emphasized folk conventions. It accommodated local practices.

The Dravida school of Mitakshara law re-interpreted the Dharma Shastras to accord with customary law prevalent in pre-historic South India. The Dayabhaga code integrated text-centered principles with regional traditions in Bengal. Other legal statutes such as the Thesavalamai in Jaffna and the Marumakattayam of Kerala were specific to certain districts or castes. The Thesavalamai was the traditional law of the Tamil Kingdom of Jaffna in early medieval Sri Lanka. It was subsequently codified by the Dutch in 1707 CE and is still upheld by the Sri Lankan judicial system.

Despite such diversity, a common Hindu legal tradition exists. Similar statutes were present in different regions across the Indian subcontinent. The principle of adoption enunciated in Mithila i.e. North Bihar, approximated that of the Thesavalamai. The woman had the independent right to adopt children on her own. Matrilineal modes of succession existed likewise in several non-contingent regions. The relocation of a man to the bride’s household, known in the Kandyan regions of Sri Lanka as the Binna marriage, was termed the Ghar Jamai in North and West India. An underlying unity of syntax existed beneath the real heterogeneity of the Hindu world. A common deep structure generated broadly similar legal codes and a civilizational continuum.

Legal Pluralism

Due to the emphasis on folk convention, Hindu jurisprudence recognizes marriage practices that differ across region, caste and community. The Dharma Shastras concede various marriage conventions that include the Brahma, the Gandharva, the Daiva and Asura. The Brahma marriage, known as kartpiyal in early Tamil literature, is the formal, community-sanctioned and patriarchal union. The Gandharva marriage, known in early Tamil as kalaviyal, is centered on the mutual sexual consent of man and woman and the consummation thereof. There was no ceremony. The legal texts recognize the lawfulness of Gandharva unions in several contexts. Polyandra likewise was practiced by the Nairs of Kerala, a custom shared by the Mukkuva of Eastern Sri Lanka[v]. Mukkuva law incidentally was the traditional law of matrilineal Tamil residents in Eastern Sri Lanka and subsequently codified by the Dutch in 1707. The Mahabharata has reference to polyandry. The Dharma Shastras permit polygamy on condition that the husband reimburses his first wife before consummating a second marriage[vi]. The legal texts affirm discrepant practices in different contexts.

The Sanskrit treatises reconcile such differences within a common legal framework. Sections within the Manu Dharma Shastra forbid divorce. The colonial authorities enforced this prohibition except in instances where caste custom explicitly permitted re-marriage. A careful assessment of the classical texts reveals, however, legal allowance for divorce. It was the later interpreter of the law who took a rigid stance against divorce. The Thesavalamai, for instance, allows for the division of assets when husband and wife live apart and consider re-marriage. The pre-colonial era Vanniyar in Tamil Sri Lanka took divorce for granted[vii]. The attitude towards divorce in Hindu jurisprudence is context-bound and dependent on local custom.

Hindu law was not irrevocable. Differences in interpretation facilitated legal innovation in the face of next contexts and challenges. The legal commentators adapted the principles of jurisprudence to shifting conditions. The Brihaspati and Narada Dharma Shastras affirm that the basis for legal decisions should not be limited to the classical texts. Jurisprudence needs to conform to reason for it to reflect Dharma[viii]. The Apastamba Sutra asserts likewise that decisions of corporate and popular bodies constitute a valid source of law[ix]. The 500 Lords of Ayyavole, the Nanadesis, the Nagarattar and the Manigramam were part-Tamil trade guilds that traded with Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaya and Sri Lanka in early medieval times and helped transfer Sanskritic cultural norms to these areas.

The Manu Dharma Shastra is conservative and inflexible in matters of caste and gender. This text is dated to the 1st century CE. The liberal Yajnavalkya Dharma Shastra however reveals a more developed legal procedure. This text is generally affixed to the Andhra dynasty of the 2nd century CE[x]. The later Parasara Dharma Shastra is even more enlightened in its approach to law. A linear development in legal thinking, therefore, took place in time. The process of innovation ceased, however, with the colonial encounter. The courts no longer made decisions based on changing contexts and relied instead of medieval commentators. Traditional jurisprudence had become fossilized and conservative under European rule.

Social checks and balances

A division of labor into hereditary castes was enunciated in the Hindu world view. The texts envisioned the inter-connectedness and inter-dependence of the different societal segments. A corporatist social community was affirmed. A sense of community cutting across social divisions was asserted through ritual – be it the harvest, the king’s coronation, temple observances, marriage and funerals.

A symbiotic relationship existed between the different castes. This social system facilitated a complex system of labor specialization in the absence of a fully monetized economy. The Sanskrit terms, jati, kula, gotra, varna etc, denote a service or occupational role[xi]. These have a multiplicity of meanings, i.e. family, tribe, race, caste etc. Castes were industrial guilds in classical and medieval society. They were incipient professions and specialized trades. Each caste had the sole right to supply a specific commodity[xii]. It served as a trade union of sorts, a benefit society and a form of social insurance. Industrial specialization enhanced excellence and workmanship.

The segmented, albeit inter-connected, social system checked political absolutism and arbitrariness. The village communities and urban trade guilds were autonomous locales. The head of the village, the caste headmen, the court of the guilds, and the king’s officers each shared legal adjudication[xiii]. Such autonomous multi-centered political formations inhibited royal despotism. Sectarian groups, immigrant communities and specialized guilds were incorporated within this inclusivist framework. Each such group was autonomous in matters of law and culture. That was the Hindu ethos.

Tambiah introduces in his works the concept of galactic polities. The borders of such political formations were blurred and imprecise. A series of satellite principalities and provinces replicated the center in structure. Heterogeneous groups were positively placed and incorporated in distinct niches. There was a decentralization of authority. This inclusivism represented a broader civilizational framework distinct to the Hindu high tradition. Such polities flourished in the Indianized kingdoms of South and South East Asia. It was this political formation that the Dharma Shastras had envisaged[xiv]. This broad inclusivist and adaptive legal system gave continuity and resilience to a socio-cultural Hindu world view in times of political and military uncertainty.

That said, the classical legal framework sanctioned differential rights. It legitimized a network of unequal obligations between the ecclesiastical classes, the landed agrarian castes and the artisan/service castes. It was explicitly hierarchical. The concept of untouchability was one outcome of this social system. The texts rationalized serfdom in terms of ritual pollution. The entire concept of caste pollution represented a flawed dimension in Hindu social thought. Jurisprudence, moreover, as in most pre-modern societies, had a gender bias. This was seen in the differential rights in marriage, divorce, re-marriage, inheritance and property. A patriarchal textual perspective sidelined women and often denied them a legal persona. The flawed exploitative elitism, hierarchy and gender exclusivism of the legal texts was unfortunate.

Conclusion

In short, a broad coherent theoretical perspective demarcates Hindu jurisprudence. While Hindu law is region and community-specific, it integrates broad concepts and micro-level practices. It is both a textual inheritance and a series of customary statutes. It adapts to changing contexts while also demonstrating certain key principles over time. Brahmanic jurisprudence posits a corporatist ethos and values. This would be in keeping with the traditional emphasis on interpretation, evolving practice, popular decisions and reason. The dynamism of Hindu jurisprudence makes imperative such reform. Hindu law, sans its hierarchy, has much to offer contemporary humanity.

(.)

Notes and references

[i] ‘Indian Law’ in Encyclopedia Britannica v.12 1947.

[ii] Manu’s Dharma Shastra is considered the pre-eminent work of Hindu jurisprudence. He is known in the Sanskritic tradition as the law giver par excellence.

[iii] P.B. Gajendragadkar,. ‘The Historical Background and Theoretic Basis of Hindu Law’ in The Cultural Heritage of India (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama) v. 2, p.426

‘[iv] Indian Law’ in Encyclopedia Brittanica v.12 1947.

[v] H.W. Tambiah, ‘Pre-Aryan Customary Laws’, in International Association of Tamil Research, Proceedings of the First International Conference Seminar of Tamil Studies (Kuala Lumpur: 1968) v. 1, p 358.

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Ibid, p. 359

[viii] P.B. Gajendragadkar, ‘The Historical Background and Theoretic Basis of Hindu Law’ in The Cultural Heritage of India (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama) v. 2, p. 426.

[ix] The decisions of corporate bodies are known as samayas which are a source of Hindu jurisprudence in their own right.

[x] Ibid p. 427

[xi] K.M. de Silva, A Short History of Sri Lanka (Delhi: Oxford University Press 1981) p. 41.

[xii] Ibid. p 147.

[xiii] Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage (New York: Simon and Schuster 1954) P. 483

[xiv] S.J. Tambiah, Buddhism Betrayed: Politics and Violence in Sri Lanka (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992) pp. 173-175.