Tracing India’s Constitutional History: 3

The Shrutis and the Smritis broadly make up India’s ancient legal literature. While the Shrutis laid down certain broad principles which were later developed into law, the Smritis specifically dealt with civil and criminal law. This part attempts to understand the fundamentals of some important works that played a crucial part in the evolution of India’s legal system.

The Vedas or the Shruti

Shruti literally means “that which is heard.” Shrutis were subsequently handed down from generation to generation orally. Shruti was considered to be apaurusheya or “not of human origin.” Shrutis typically include the four Vedas. Thus, Vedanta (literally, the end of the Vedas or the concluding portion of the Vedas) is also part of the Shrutis. Some scholars also include auxiliary works called Vedangas (limbs of the Vedas) as part of the Shrutis.

Vedas do not deal exclusively with legal aspects, but prescribe a certain value system for the society to follow. In other words, the Shrutis lay down both negative and positive injunctions, which in turn formed the foundation of the Smriti laws. A few examples will suffice to illustrate the nature of these injuctions:

Satyam Vada – Speak the Truth

Naanrutam Vadeth – Never tell the untruth

Dharmam Chara – Follow Dharma

Yaani anavadyani Karmani Taani Sevitavyani No Itarani – Perform only such acts which are not forbidden.

These injunctions laid down by the Shrutis later became the founding blocks of provisions in the Smiritis. For instance, the injunction of Satyam Vada and Naanrutam Vadeth formed the basis of provisions which dealt with punishments for perjury, providing false evidence and such other acts. Thus it can be said that the Vedas were the primary and inviolable source of Dharma, and the Smritis could not incorporate legal provisions that were contrary to the principles laid down by the Vedas.

However, the Vedas cannot be considered to be the proper legal texts of the Hindu legal system because they don’t directly deal with the provisions of civil and criminal law. They only provide a basic framework which then inspired the Smritikaras (authors of Smritis) to compile the Smritis within that framework. Therefore, we need to refer to the various Smritis, Dharma Sutras and other commentaries on the Smritis to understand in full measure the import of the Dharmashastras. Yagnavalkya names more than twenty people as authors of Dharmashastras of which Manu, Atri, Vishnu, Harita, Apastamba, Brihaspati and Katyanana enjoy prominent positions.

Dharma Sutras

Some of the most ancient legal works were the Dharma Sutras, which were in the form of aphorisms. Dharma Sutras laid down rules and laws that covered almost the entire gamut of human activity. The Sutras were divided into three broad categories –

- Srauta Sutras – which regulated rituals

- Grihya Sutras – which related to matters of family life

- Dharma Sutras – which dealt with civil and criminal law

The important sutras that were considered to be of high authority and antiquity were Gauthama, Baudhayana and Apastamba Sutras.

Among these, Gauthama’s is the oldest. He extensively covered aspects related to marriage, inheritance, partition and so on. The next sutra in order of antiquity is the Baudhayana Sutra, which deals with several matters addressed by Gauthama. However, Baudhayana additionally recognizes the need for the State (King) to regulate commerce and trade by means of collection of taxes and issuing of licenses. We find mention of various kinds of levies and taxes like sea custom, excise, sales tax and so on.

However, the Apastamba Sutras are considered the most influential. Scholars opine that Apastamba was a revolutionist and his expositions were clear and forceful. Many subsequent law givers refer to Apastamba and quote him extensively, a fact which reflects his lasting influence. Apastamba stands out because he was not a conformist. He changed a lot of prevailing rules and customs which he deemed were not suitable to the changing needs of the time. For instance, he condemned the practice of polyandry in the guise of Niyoga and also took exception to the then prevailing practice of begetting a child from one’s sister-in-law for the sake of alleged spiritual benefit. The commentator Sarvadhikari says, “It can be seen that Apastamba was a revolutionist to the backbone and was determined to replace the old order of things by more refined and civilized institutions”. It is clear that ancient Indian juridical system allowed great leeway for changes to be made to suit the demands of the time and that the accusation by Marxist historians that Indian society stagnated as a result of rigidity falls flat.

The other important lawgiver was Harita. His sutras laid down the rule of Prag-nyaya, which is the modern principle of res judicata. This is a very important development because it shows that the principle of finality of judgment was conceptualized and incorporated in ancient India hundreds of years before it was implemented anywhere else in the world.

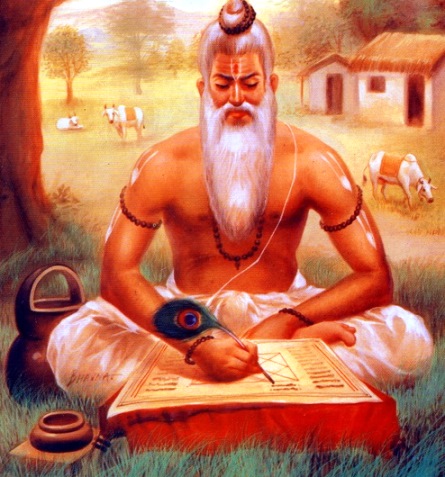

Smritis

Although these Sutras held a high value and were revered, the most authoritative and extensive works of law are the Smritis. All the legal principles scattered in the Vedas, the Dharma Sutras and the prevailing custom and usage of the day were collected, collated, compiled, and arranged in a cohesive manner in the Smritis. In this respect, it can be said that the Smritis were the oldest attempt at the codification of and compilation of law. In addition to other religious and substantive legal subjects, the Smritis extensively covered subjects such as evolution of courts, procedure for the appointment of judges and other procedural aspects for the enforcement of substantive law. Some of the most influential Smritis are the Manu Smriti, Yagnavalkya Smriti, Narada Smriti, Parashara Smriti, Brihaspati Smriti and Katyayana Smriti.

Before reading any further about the Smritis, it is necessary to appreciate the rules regarding the interpretation of the Dharmashastras. Both the rules as well as the procedure of their interpretation were highly evolved in ancient India. Mimamsa or interpretation became inevitable to understand the real meaning of the provisions of the Dharmashastras. This was because many a time, the injunctions expressed were in short and cryptic sentences. The principles of interpretation and the legal maxims laid down in these texts are highly illuminating and stand as testimony to the eminence of the scholars of those times.

Parashara Smriti – Among the Smritis, the Parashara Smriti is considered to be the highest authority in the Kali Yuga and holds a high rank among ancient Hindu legal works. Unfortunately, Parashara’s treatise on law has not been recovered in full. Most of the subsequent writers, including Yagnavalkya and Kautilya, quote Parashara frequently. Kautilya in his Arthashastra quotes Parashara as many as six times on issues related to politics, which can be used to infer that Parashara might have written another work on politics much before Kautilya’s time.

Manu Smriti –The code of Manu forms an important landmark in the legal history of India. Most of the law writers, beginning with and after the 2nd Century have attached great importance to Manusmriti, which was widely recognized as the most authoritative legal work of the time. The present Manusmriti seems to have been recast or compiled over many years by Brighu Maharshi and it is felt by many scholars that probably Sage Brighu himself gave the name “Manu Smriti” to the compilation.

However, right from the Rg Veda, one finds that almost all authors of Dharmashastras refer to the opinion of Manu and regard him as the first law giver. Interestingly, we find references to several Manus such as Swayambhu Manu, Vridhha Manu and Pracheta Manu in many places. Also, while explaining the origin of kingship, it is said that people elected Vaivaswata Manu as their first king to secure law and order and that he compiled the Manusmriti. Therefore, it has not been possible to say with certainty which of these Manus was the first law giver. However, this ambiguity with the authorship of Manusmriti does not take away the pre-eminent position it enjoys in the annals of ancient legal works of India. The compilation of Manusmriti around 200 B.C. was possibly the result of the need for codification of all the rules of Dharmashastra in vogue during the time. This authoritative compilation of all the rules of law, custom and usage in vogue contributed to Manusmriti occupying such an important position in the pantheon of legal works.

The Manusmriti

The Manusmriti is divided into 12 chapters and consists of 2,694 verses. The following is the subject matter of the 12 chapters:

1. Creation of the Universe

2. Definition and Sources of Dharma

3. Celibacy – Studenthood – Marriage

4. Householder’s conduct

5. Rules governing food

6. Rules governing forest hermits

7. Rajadharma

8. King’s duty regarding administration of justice

9. Duties of husband and wife – rules on partition, inheritance

10. General rules of conduct for all.

11. Seven modes of livelihood

12. Karma – the knowledge of the self.

Many scholars have written authoritative commentaries on the Manusmriti which not only exhibit the dazzling legal and literary scholarship of the time, but indicate the presence of a vibrant legal system in ancient India.

Yagnavalkya Smriti

The Yagnavalkya Smriti like the Manusmriti occupies a preeminent position in Hindu jurisprudence. On the greatness and the profound influence of this work, the renowned scholar Robert Lingat says –

Of all the Smritis which have come down to us, that of Yagnavalkya is assuredly the best composed and appears to be the most homogeneous…We are struck, if we have just read Manu, by the sober tone, the concise style and the strictness with which the topics are arranged… The result if that he reduces to one thousand or so the 2694 couplets of Manu, even though several topics are dealt in greater detail.

The Yagnavalkya Smriti consists of 1010 verses which are divided into 3 chapters, which deal with religious, civil and criminal laws and rules for atonement for sins committed.

It is said that Yagnavalkya was a learned sage in the kingdom of Mithila and that other sages approached him with a request to impart the rules of Dharma. He obliged their request. The Smriti is said to be the precepts that he delivered to these sages and philosophers in the Kingdom of Mithila.

Compared with Manu on matters such as women’s rights of inheritance and right to property, the status of Shudras and criminal penalty, Yagnavalkya appears to be more liberal. He steps up the pace of progress in the development of law by keeping in tune with the times. Several scholars opine that the significant reduction in the strict penal provisions in the Yagnavalkya Smriti is because of the profound influence of Buddha on the society.

On the significance of Yagnavalkya Smriti, the celebrated scholar Bharata Ratna P.V. Kane says:

On account of the paramount importance of Mitakshara in modern Hindu law as administered by British courts in the whole of India, the Smriti of Yagnavalkya has indirectly become the guiding work for the whole of India and this position it richly deserves by its concise but clear statement of principles, its breadth of vision and its comparative impartiality towards the claims of both sexes and the different varnas.

The prestige and authority of Yagnavalkya Smriti have been greatly advanced by the celebrated commentary of Vignaneshwara’s Mitakshara. Mitakshara has been accepted as supreme in the whole of India except the province of Bengal, where the Dayabhaga School is in vogue. It still forms the basis for the personal laws of Hindus to a great extent. Thus, it can be said that Yagnavalkya Smriti continues to bear significant influence on even the present day Hindu legal system.

Other Smritis and works

Apart from the aforementioned works, the Narada Smriti and the Katyayana Smriti also enjoy a high position of importance in Indian legal lore. While the Manu and Yagnavalkya Smritis dealt with many religious aspects of life, the Narada and Katyayana Smritis dealt purely with substantively legal questions. They are known for laying down the procedure to be followed by courts and contain detailed provisions relating to pleading, evidence and modes of judgment. They throw illuminating light on the political and social institutions during the period they were written. Many progressive changes were made in the areas of partition, inheritance, acquisition of property by women, rights of unmarried daughters, rights of minor children among others. Scholars say that these smritis indicate that ancient Indian jurists never hesitated to take a progressive view and did not feel themselves bound by the opinion expressed by earlier jurists and instead gave expression to their own thoughts freely and made sure the social and political institutions never remained static.

In addition to these Smritis, the Ramayana and Mahabharata and Kautilya’s Arthashastra can be considered as definitive landmarks in the evolution of jurisprudence in India.

To be continued