Nations, Nationalism, and India as a Nation

Image Courtesy: kractivist.org

Editor’s note: Part of the Hinduphobic discourse involves the strident denial of any uniquely organized society and a civilizational entity within the larger Indian/South Asian geographic region, and the claim that whatever residents in that area believed, wrote about, and offered the world was not “religious”. Thus, the assertion that there is nothing like India as a nation and Hinduism as a “religion,” and therefore any claims Hindus make about “Bharatavarsha” or “Hindu/Sanatana Dharma” are false. The two-part essay below is a summary of the work refuting the assertion that there is “nothing” like “India/Bharatavarsha”.

PART I

Introduction

Scholars used to the modern definition of a nation or nation-state cannot imagine a nation as a civilizational continuity based on traditions, culture, and rituals. Unlike other modern nation-states based on some homogenization variable (mainly linguistic), spiritual places, and important texts have defined Bharat’s geography. India takes shape almost automatically if we place on the map all the holy rivers and places available to us and identified for us since ages. Has the geography helped? We do not know whether the specific shape of India is a cause or consequence of the nation of people who call themselves Indians.

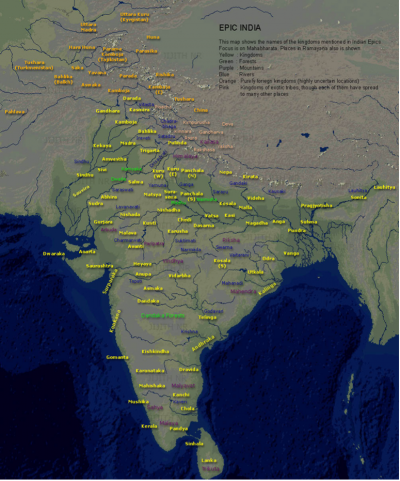

As an example, the Mahabharata (Bhishma Parva) gives an exhaustive list of mountains, rivers, and kingdoms forming the land of Bharatvarsha correlating with the entire Indian subcontinent. The rivers include the Ganga, Sindhu, Saraswati, Godavari, Narmada, and Kaveri. Amongst the many named kingdoms across the country, it identifies many southern kingdoms, some of which are clearly identifiable today: Dravidas, Keralas, Karanatakas, Cholas, and Vidarbhas. It says, “These countries are, besides, the abodes of many Kshatriya, Vaisya, and Sudra tribes”. It also mentions Kasmiras and the Kalingas. The passage leaves no doubt about the geographical unity of Bharatavarsha as a single unit. The Mahabharata offers a picture of the breadth of Bharatavarsha too — from Gandhara (present day Afghanistan) to Pragjyotishpur (present day Assam).

“India was never a nation till the English came,” claim those who are colonialists or those who are still under the sway of colonial thinking or those who are still beholden to Western largesse. India as a nation and as a civilization can best be understood as the place where diversity was the norm and the essence of nationalism was in protecting the diversity of the country. India is simply the longest continuing civilization — at least five thousand years old. Modern theories of nations, nationalism, or state, only a few hundred years old, may not make much sense in the understanding of India and the real idea of India.

India has diverse social, linguistic, and spiritual practices, and the cultural heritage acts as the cement that binds the nation, says Michel Danino. Because of this, India transcends boundaries of what conventionally constitutes a nation. This binding cultural heritage accommodates Vedic, non-Vedic, Jain, Buddhist, Tantric, Puranic, Sikh, folk, and tribal concepts, forms, attitudes, customs, and practices. Rabindranath Tagore said famously on India’s cultural unity: “India has all along been trying experiments in evolving a social unity within which all the different peoples could be held together, while fully enjoying the freedom of maintaining their own differences… This has produced something like a United States of a social federation, whose common name is Hinduism”.

Tagore, Sri Aurobindo, and Swami Vivekananda, stressing the spiritual and cultural aspects of India, recognized the recentness of modern nationalism and the possible evils it could generate. Colonialism and the world wars were a direct outcome of the nationalistic spirit intricately linked with the nation. Tagore, rejecting the term “nationalism” in the western sense, felt that that society as such has no ulterior purpose like economics or politics but was a “spontaneous expression of man as a social being”. The political side was only for the purpose of self-preservation.

The forcible application of western theories to the Indian context led to the division of country, first on a religious basis, and followed by the states on a linguistic basis. An artificiality in cultural identities is now the result of such policies. Our ancient kingdoms included people who spoke many languages without much dispute amongst the native speakers. It is time that we should begin viewing Bharat as a nation through our own cultural and philosophical lenses.

Defining Nations, States, Nationalism, and Sovereignty

“Nation” (Latin natio” — birth) refers to a group of people implying notions of a blood relationship or a shared heritage and language. The extension – “nationalism” — emotionally identifies with one’s own nation and supports its interests (intellectually and physically) even to the detriment of other nations’ interests. This “nation” or a group of people in turn link to the claim of an independent land or “state” for itself. Territory, in the past few centuries, and particularly since the 1860s (Bismarck trying to unite the German people), became an ideological basis of many nationalist causes. “Homeland” as the basis for the nation is evident from the earliest Jewish claims in the Old Testament. The perceived inseparable tie between “Blut und Boden” (Blood and Soil) has caused numerous wars where more than one nation (or a group of people) laid claim to the same territory (or state).

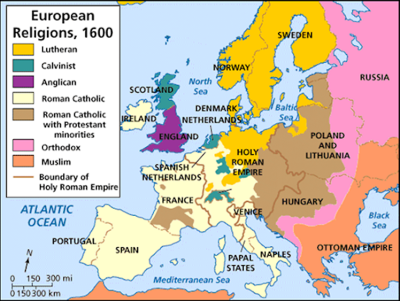

The nation-state is now a combined idea where both words mean the same. Problematically, there are at least 8,000 nationalities (actual or potential) in this world, and their postulated “homelands” overlap with “distressing frequency,” as Peter Ravn Rasmussen notes. Extreme nationalist ideals have been the reason for cruelty, persecution, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and wars to redefine boundaries. In a pure form, the state is a political unit, separate from emotions of nations and nationalism, with a defined territory and a partial or total control of all its offices. The political theory of evolution of the modern states and nations is however a recent construct and relates historically in an intricate manner to the religious wars of Europe and the Westphalian treaty. How could events in 16th century and 17th century Europe come to define our country?

Martin Luther and the Spread of Protestantism

Martin Luther (1483-1546) is arguably the one man who has most impacted the world we live in, and he has been influential in how our intellectual discourses on these matters flow and are directed. He initiated the Protestant Reformation Movement against the Roman Catholic Church with his Ninety-five Theses in 1517. The Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor excommunicated Martin Luther and made him an outlaw. He translated the Bible, the only source of divinely revealed knowledge, from Latin into vernacular German to make it widely accessible and thus removed the authority of the priests. Lutheranism spread widely and rapidly among the many German-speaking states of the Holy Roman Empire and even to France causing much religious tension. Protestants now condemn it but Martin Luther also espoused anti-Semitic views.

In 1555, the Peace of Augsburg, between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Protestant League, ended temporarily the religious struggle. Now, rulers could choose either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism as the official confession of their state with the principle of Cuius regio, eius religio (“whose realm, his religion”). Citizens not confirming to the ruler’s views could migrate to other lands. However, if the ruler changed his religion, the inhabitants of that state did not have to do so.

This treaty, however, did not include other Protestant denominations like Calvinism and Anabaptism which still had to face the danger of persecution and heresy. These groups had to wait for inclusion till the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. Calvinism, which includes diverse traditions with a wide range of influences, started with Calvin in 1541. Despite many commonalities, there were some theological differences with the Lutheran Church. In the major phase of Protestant persecution, Calvin fled from France to settle in Geneva.

Anabaptists and their later branches like the Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites believe in delaying baptism until the person confesses faith in Christ. They were strict followers of the scripture (like the Sermon on the Mount) even if it conflicted with civil society, including avoiding participation in civil governance and the military too. During the 16th and early 17th century both Protestants and Roman Catholics persecuted them. After starting in Switzerland, Anabaptism spread to modern-day Austria, South Germany, Moravia, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

England, initially Catholic, had its own reasons to turn Protestant. During the reign of Mary I, there was an attempt to return to Catholicism which included burning a few hundred Protestants at the stake. In the meantime, France saw eight civil wars between 1562 to 1598 between Catholics and Protestants that led to the deaths of two to four million people. The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in France (1572) saw Roman Catholics killing thousands of derisively named Protestant Huguenots.

The Religious Wars of Europe

The undercurrent of religious discriminations set the stage for the Thirty-Years War in Europe, intensely divided over various Christian denominations, between 1618 to 1648. The Holy Roman Empire was a fragmented collection of independent states which espoused different religious beliefs.

Briefly, the Rhine lands and those south to the Danube were largely Catholic; the Lutherans dominated the north; and Calvinists dominated west-central Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. The war began when the newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, a devout Catholic, tried to impose Roman Catholicism on all his people. The Bohemian Revolt between 1618 to 1620 began the war. It started with the Defenestration of Prague incident when Protestants threw the representatives of Emperor Ferdinand II out of the window. However, the Protestants lost heavily in the ensuing war.

In the next Danish phase, the Protestant kings of Denmark (Christian IV) and Sweden (Gustav Adolph) got involved in the war against the Catholic states between 1630 and 1635 and helped regain much of the lost Protestant territory. In the meantime, France, though Roman Catholic, became a rival of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain because they had severe political issues with the Spanish Habsburgs holding several territories on France’s eastern border. France entered the war in 1634; and in 1648, the combined Swedish and French armies defeated the opposition. The Battle of Prague was a final decisive victory in 1648. Eight million people died from military engagements, famine, and plague. Twenty percent of the total population of Germany died during the conflict.

After several battles and interspersed treaties, finally the Peace of Westphalia closed the chapter of the Thirty Years War. Incidentally, it also brought an end to the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648) between Spain and the Dutch Republic (Netherlands). The peace negotiations of Westphalia involved 109 delegations representing European powers. The rulers of the Imperial States regained power; there was affirmation of cuius regio, eius religio (whose realm, their religion); the minority denominations could freely practice their faith; Switzerland became independent; and Rhine River became a free navigation route.

Sovereign States as an Outcome of Westphalian Treaty

Sovereign states were the outcome of the Westphalian Treaty. Though some disagree, this was a watershed moment in history when independent sovereign states based on territory laid the basis for a better structured political world. Many Western scholars feel that the Westphalian model is now central to international law and the prevailing world order. The Westphalia settlement emphasised the separation and equality of states rather than the unity of Christendom. Territorial sovereignty implied only one absolute power (kings or government) within the territory.

Article 2(1) and Article 2(7) of the UN embeds two dominant conceptions of the Treaty of Westphalia by stating this: a) “The organisation is based on the principle of sovereign equality of all its members”; and, b) “Nothing contained in the present charter shall authorise the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state…,” respectively. Scholars keep repeating those ideas from the Westphalian Treaty about sovereign equality and exclusive domestic authority, and how they guarantee the best peace between nations. One scholar says that as a first treaty of modern international law, its significance is everlasting because it introduced the modern state system and enabled the peaceful co-existence between equals. But, has it?

Emergence of People, Nation, and Nationalism: The British Surge

Earlier, the Latin natio was originally a term of contempt used to identify communities of non-Roman citizens in Rome. Later, into the Middle Ages (5th to 15th century), “nation” became applicable to foreign students studying in European universities. At the University of Paris, the foreigners were divided into four nations according to geographic origins: France, Germany, Normandy, and Picardy (or the Low Countries — Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg). These university “nations” developed common opinions. The nation concept morphed into a “community of opinion”.

From the Church Council of Lyon in 1274, “nation” evolved into a term for decision-making “religious and secular” elites at the councils. Thus, the accepted meaning of nation in continental Europe until the mid-eighteenth century applied only to the nobility. The word people implied the lower social strata.

England was the epicentre of “nationalism,” an accident of history, originating in The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487). A series of self-destructive battles wiped out many nobles and aristocrats — the “blue-blooded”. Henry VII had to recruit his aristocracy from the “red-blooded” common folk. A unique and massive social mobility ensued from the lower to the upper orders. This new aristocracy, in a move to justify and legitimize the new ascended positions of the common folk, declared the English “people” as a “nation”. A previously hierarchical society became a society of equals.

The equivalence of “people” and “nation,” was thus a linguistic event causing a revolutionary social transformation. Social stratification became fluid: will, ability, and chance allowed individuals to move up and down the social ladder. As scholars note, paradoxically as secularization made God irrelevant, the simultaneous Protestant Reformation greatly helped English nationalism by reinforcing “popular sovereignty” and equality of membership. Literacy was encouraged among the English population. “Nation” did not exist in the original Bible but the King James English version presented the Bible through the lens of national consciousness strengthening the message of dignity, equality, and freedom.

The Protestant Reformation also helped establish the principle of national sovereignty ignited by a mundane event. Henry VIII wanted to divorce his first wife but the Pope refused to grant the divorce. The 1533 Parliamentary Act of Appeals declared that the Pope had no right to meddle in English affairs because England was a sovereign community. The English empire separated itself from Rome joining the forces of the Reformation. This liberation of the British Empire inspired future national liberation movements. Even though individuals were autonomous, the notion of the “dignity of the nation” gained prominence. National consciousness (nationalism) became inherently competitive.

England expanded suddenly in a never-ending race for respect that fundamentally changed the world. As a scholar says, the unbelieving European neighbors watched in amazement as the little England of 1500, poor in natural resources and academic learning, raced forward as a great power within a century. Despite some rebellions by the Scottish, by 1700 England had raced far ahead of the rest in all fields.

Capitalism and science, the defining features of modernity, were the two important outcomes of a determined English national effort. It was nationalism and the competition for national prestige that produced modern economies and capitalism. The same concern for national dignity also made it culturally competitive. National values made individual activity a natural focus. Unwilling to accept traditions, the English espoused a primitive cultural relativism — what was good for one period was not necessarily good for another. Three technological inventions — the printing press, firearms, and the compass — also reaffirmed this view of a primitive past and an advantageous modernity.

Nationalism and its Consequences

By the end of the nineteenth century, nationalism was a popular movement with flags, national anthems, patriotic poetry and literature, public ceremonies, and national holidays. Nationalism sought to integrate the increasingly powerful working class into the nation. This was possible by mass literacy due to primary education and the spread of popular newspapers. Nationalism came to stand for social cohesion, order, and stability. It challenged socialism even as socialist ideas like the values of community and cooperation appealed to nationalists in the developing world.

Patriotic fervor and nationalism, increasingly chauvinistic and xenophobic, labelled other nations as “alien” and fuelled colonial expansion that intensified dramatically in the 1870s and 1880s. It also contributed to a mood of international suspicion and rivalry, leading to the world wars. Military glory became the ultimate parameter of national greatness. Colonized countries also evolved nationalistic feelings to throw off the colonizers. In a sense, the colonizers took with them the seed of their own destruction — the doctrine of nationalism.

Theories of Nationalism – Schools of Thought

“Nations” first or “nationalism” first? The great chicken and egg question intricately sustain and perpetuate each other. The Modernist School (Anderson and Gellner) propose that nations and nationalism are products of modern industrializing societies created for economic and political purposes by the elite using either language, a constructed culture, or history. The modernist schools look at a nation as a social construct, either with the aim of achieving economic growth or achieving cultural homogenization through educational content in a vernacular language. Nationalism mobilizes populations and utilizes the collective effort to improve the nation’s importance. Japan apparently is an example of this artificially constructed nationalism in the 19th century.

Anderson explains nationalism as a collective construct — an “imagined political community” — instead of as a natural phenomenon linked together by historical events. The feeling of nationalism in an ethnic or racial group could lead to a feeling of national identity. Nationalism rises before the nation, the latter being a social and political construct, with amendable boundaries. By believing sovereignty as the reigning principle for the nation-state, the nation receives a sense of freedom and would even make its citizens go to war to protect the nation. Despite elastic boundaries, Anderson believes that nations must be finite, with a demographic consistency and geographical restrictions. Outside the boundaries, there are other nations with their own identities.

Ernest Gellner also believes that nationalism arises first. He strongly reiterates this by saying that “nationalism is not the awakening of nations to self-consciousness: it invents nations where they do not exist”. Members of a nation would feel connected to their fellow members without ever meeting them. This relies on commonalities such as sharing the same history, heritage, traditions, goals, interests, or culture. The media, through “print capitalism,” makes it possible for the nation to be “imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion”.

The Primordialist School of Nationalism (Anthony D. Smith) defines the nation as “a named human population sharing an historic territory, common myths and historical memories, a mass, public culture, a common economy and common legal rights and duties for all members”. Proponents believe that nationalism builds upon existing beliefs of a population sharing the same kin or ethnicity. Nations are thus a “natural entity” and come before nationalism. The pre-modern ethnic and cultural foundations are strong emotional forces in nationalism and national identity. This ethno-symbolic approach identifies traditions, symbols, myths, and memories of a nation`s ethnic roots to build national identity, national unity, and national autonomy, and therefore the nation. This approach tries to show that nations and their ethnic roots have a legitimate historical link.

Another idea is that of cultural nationalism which is the romanticizing of the nation as a unique historical and organic whole in contrast to the “rational” political nationalism. Though anti-modern in nature, cultural nationalism may also serve as an agent of modernization by enabling a people to “recreate” themselves.

Nationalism as Secularization of Christian Theology: Balagangandhara’s Thesis

In a recent article, “People and Nations,” Prof. SN Balagangadhara proposed that at a fundamental level nationalism is the secularization of a theological idea. He writes that ancient Romans saw “traditions” as defining a group of people. Different groups of “people” belonging to different traditions could live together in a “nation” where the fundamental living principle of different traditions is an indifference to differences. When Christians entered, the Romans did not group them as “peoples” because they did not have an ancestral tradition to follow.

Subsequently, as Balagangadhara shows (The Heathen In His Blindness), Christians redefined the notion of “peoples”. They became a community of people because of their “religio” and hence united in Christ and in God. A “unity in Christ” defined the Christian community as a group of people now. The belief thus generated a Christian notion that belief in one single God defines a group of people. One of the most powerful ways that Christianity spread, Balagangadhara says, is through the secularization of theological ideas. The secularization thus took the form of a “common religion” defining one “group of people”.

This again might offer an explanation of the negative aspects of nationalism (colonialism, world wars) which we see at a later date. Going by Balagangadhara’s hypothesis of cultural differences, the Western roots in religion is the seed for both atheism and science as the question of “why” is an important component of its growth. Indian culture is rooted in traditions where the more important question is “how” and the culture focuses on performative learning. Religion gives importance to the spread of doctrines and conversion of people to the “true religion” and hence it has always an expansionist drive. It is perhaps these roots which gave the West such expansionist ideas and the applications of force in its quest to dominate the world.

A culture based on traditions has rituals at its backbone which unites people. At a fundamental level, religion says, “I am true and you are false,” whereas traditions say “I am true and you are not false”. The remarkable assimilative and absorptive capacity of India and its failure to go outside its borders could be a manifestation of the fundamental makeup of the culture of India or Bharatavarsha. In such a situation to wonder why India is or is not a “nation” in the western manner fails to make sense. It is like asking a Belgian priest whether he is a Brahmin. Both the question and the answer, though in plain English, fall outside the ambit of coherence. What brings the people of the West together would never make sense to understand what brings the people in India together. The theories of nations and nationalism (like secularism) may simply be inadequate to understand India.

In the next section, we shall see how Bharatavarsha differs from the western notions of nation-state and how it comes together as a civilizational unity, more than five millennia old, by different mechanisms altogether. The religious and linguistic homogenization, which the West is so fond of, was the cause for splitting of the land in the past and continues to split the country at present, based on linguistic chauvinism.

***

PART II

In Part 1 we saw the definitions of nations and nationalism and how they evolved across centuries. In this section, we shall see how these theories of nations and nationalism fail to make sense while trying to define and understand Bharatavarsha. When someone claims that India was never a nation, it only betrays a poor understanding of the nature of India’s nationhood.

The Notion of Bharatavarsha — A Sacred Geography and a Cultural Civilization

India can be described as a diverse but united, cultural, civilizational space but not as a political unit in the western sense. The earliest reference (326 BCE) to a quadrilateral shaped united land (the Indus River as the western boundary, the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains in the north, and the seas skirting the two sides) is in the Greek descriptions during Alexander’s times. As the latest book by Meenakshi Jain (The Hindus of Hindustan) informs, Alexander’s historians mentioned India measuring sixteen thousand stadia (1,838 miles) from the Indus to the mouth of Ganga. From the mouth of Ganga, it was another 16,000 stadia along the eastern coast to the southern tip of India; 19,000 stadia (2,183 miles) across the western coast from the southernmost tip to the mouth of Indus; and 1,300 stadia (1,496 miles) defining the western border of India along the course of the Indus river. Jain quotes Cunningham (1871) who says, “The close agreement of these dimensions… with the actual size of the country is very remarkable, and shows that the Indians, even at that early date in their history, had a very accurate knowledge of the form and extent of their native land”.

As Michel Danino writes that it were in fact the Ramayana and the Mahabharata which were the major tools for integration rather than the Vedas and the Upanishads. The references to the great epics are all over the country and even in places like Indonesia where local traditions always link in some way to the two great epics. In a mutually augmenting phenomenon, people from different areas of the country identify their place or lineage with incidents, places, and peoples in the Puranas or Itihaasas.

Sarayu, Ayodhya, the Son River, Vaishali, Mithila, Kosala, Chitrakoot, Mandakini, Godavari, Lanka, Dandaka forest, Pampa, Vindhya mountains, Narmada, Suraashtra, and many such references in the Ramayana allude to the idea of a unified Bharatavarsha where there was no restriction from traveling across these regions. Fluctuating kingdom boundaries and political divisions hardly mattered when it came to movements of peoples and the royalty.

Though some scholars maintain that the Ramayana geography restricts to the north of the Vindhyas, the Mahabharata, a massive text of 100,000 verses, is unambiguous in its descriptions and travel narratives covering Bharatavarsha extensively – its rivers, mountains, lakes, forests, and kingdoms. Irrespective of the dating of the Mahabharata (950 BCE, 1792 BCE, 3067 BCE, or 5556 BCE), Bharatavarsha as a unified entity in this text can be traced back to much before the time of the Buddha (563 BCE).

The Bhishma Parva of the Mahabharata starts with the description about the cities, countries, rivers, mountains and forests of the warriors gathered for the Kurukshetra war. Mahendra (the Eastern Ghat region in Orissa), Malaya (the Southern Western Ghat), Sahya (Northern Western Ghats), Suktiman (Bundelkhand), Rksavan (Jharkand), Vindhya (North of Narmada), and Pariyatra (Aravalli in Rajasthan) are the seven mountain ranges in Bharatavarsha.

Twenty-four verses from the Bhishma Parva names one hundred and fifty rivers including the Ganga, Yamuna, Saraswati, Indus, Godavari, Narmada, Krishna, Rushikulya (Orissa), and Kaveri across the Indian sub-continent. Thirty-two verses mention 220 kingdoms across Bharatavarsha. Of these 195 are Kshatriya provinces. Kuru-Panchala, Kalinga, Vidarbha, Surastra, Kasmira, Magadha, Dravida, Keralah, Andhras, Pahlavas, Vindhya, and such names resonate well with the present names and regions.

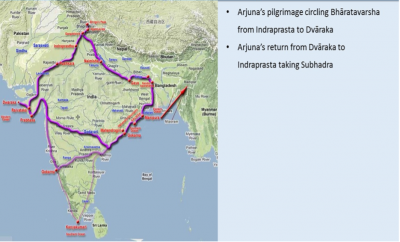

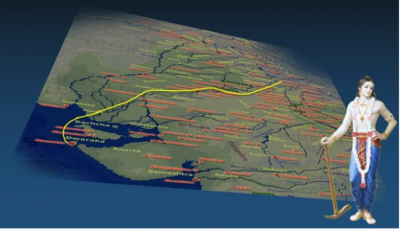

Jijith Nadumuri Ravi has made an incredible analysis of all proper nouns (places, pilgrim centers, kingdoms, rivers, lakes, mountains, forests, or seas) in the Mahabharata. The analysis and detailed maps of 100 places, 30 forests, 30 lakes, 80 mountain ranges, 60 geographical regions, 300 pilgrim places, and 80 kingdoms offer a strong argument for a culturally, spiritually, and geographically united people of Bharatavarsha. Important travel narratives (journeys, pilgrimages, and military travels) reveal the networks and an inter-relation of different parts of Bharatavarsha. Balarama’s travels, the journeys of the Pandavas in the forests or their final journey, and Krishna’s travel to Magadha are a few examples.

Similarly, chapter 19, Canto 5 of the Bhagvat Purana clearly describes the glories of Bharatavarsha. Verses describe the Malaya mountains (Southern part of Western Ghats), Sahya Mountains, Risaba, Kutaka, Kollaka, Sahya, Devagiri, Rsyamuka, Sri-saila, Venkata, Mahendra, Varidhara, Vindhya, and so on. Among the rivers, Brahmaputra and Sona get a prominent place. Other rivers mentioned are the Kaveri, Tapi, Yamuna, Sarasvati, Gomati, Sarayu, Satadru, Asikni (Punjab), Narmada, Mahanadi, Rsikulya (Orissa), Tungabhadra, Mandakini, Godavari — important rivers which purify the inhabitants of Bharatavarsha. The Vishnu Purana describes Bharata as the “land north of the ocean and south of the snowy mountains or the Himalayas”.

Radhakumud Mookerji in his classic, “The Fundamental Unity of India” and in recent times, Sankrant Sanu (Why India is a Nation), elegantly sum up the evidence for the geographical, cultural, and civilizational unity of the people. As Sanu says, for thousands of years, Indians throughout the land wake up in the morning and sing a hymn from the Brihannaradiya Purana celebrating the holy rivers of Ganga, Yamuna, Narmada, Godavari, Sindhu, Saraswati, and Kaveri as part of their daily ritual.

गङ्गे च यमुने चैव गोदावरि सरस्वति ।

नर्मदे सिन्धु कावेरि जलेऽस्मिन् संनिधिं कुरु ॥

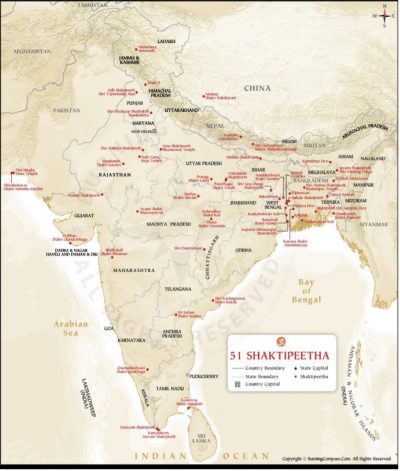

Michel Danino says, “the Jyotirlingas, the Shakti Mahapithas, and the Upapithas spread over India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Pakistan became the defining point to draw the boundaries of the country. The cultural integration began in the Harappan times and accelerated during the Gangetic civilization phase in about 700 BC. It was an organic process and not controlled by any central authority”. The consciously created networks include the Char Dhams at the four “corners” of the land; the twelve Jyotirlingas; the Kumbha mela sites (originally twelve of them); the 108 Divya Desam shrines to Vishnu; and numerous regional networks. In the Tantric schools, the legend of Shakti describes the body pieces cut by Vishnu landing at the 51 sites of Shakti Peetham temples — from Neelayadakshi Kovil in Tamil Nadu to Vaishno Devi in Jammu, and from Pavagadh in Gujarat to the Kamakshi temple in Assam.

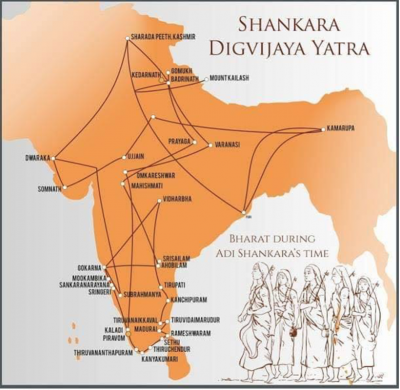

Adi Shankara’s extensive travels covered the length and breadth of country. He established the four mathas in the four corners of the country which are even today important places of pilgrimage: Dwarka (east), Puri (west), Badrinath (north), and Sringeri (south). Bhakti movement saints starting from the sixth century also reflect the cultural and spiritual unity of the people. These saints included the Alvars and the Nayanars (Tamil, 7th to 10th century), Kamban (Tamil, 11th century), Basava (Kannada, 12th century), Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (Bengali, 15th century), Annamayya (Telugu, 15th century), Surdas (Braj, 16th century), Mirabai (Rajasthan, 16th century), Tulsidas (Avadhi, 16th century), Nanak (Punjabi, 16th century), Bhakta Ramadasu (Telugu, 17th century) and Tukaram (Marathi, 17th century), amongst the many.

They wove a garland across the land speaking of our common truths, our common cultural heritage, and our ancient stories in local languages. These saint-poets evolved an immense body of pan-Indian worship around the triad of Vishnu, Shiva, and Shakti in their various forms – Rama, Krishna, Sri Venkateshwara, Sri Dakshinamurti, Durga Mata, or Kali. Diana Eck (India: A Sacred Geography) reiterates this by saying that for well over two thousand years, the “landscape of India is three-dimensional by the power of myth, narrative, and pilgrimage”.

Image courtesy: Jijith Nadumuri Ravi

Rama’s Route

Arjuna’s Route

Balarama’s pilgrimage along the Saraswati River

The Bharatavarsha of Sri Adi Shankara

Never A Political Unity?

Contrary to the colonial narratives, there were large pan-India political unifications. The Maurya Dynasty, founded by Chandragupta Maurya, dominated the Indian subcontinent between 322 and 185 BCE with the capital at Pataliputra (Patna). Under Ashoka, it extended from the present-day Assam to eastern Afghanistan, an area of five million square kilometres. Kautilya’s exhaustive Arthashastra (2nd century BCE) does not mention the imposition of a single language or traditional practice across the state.

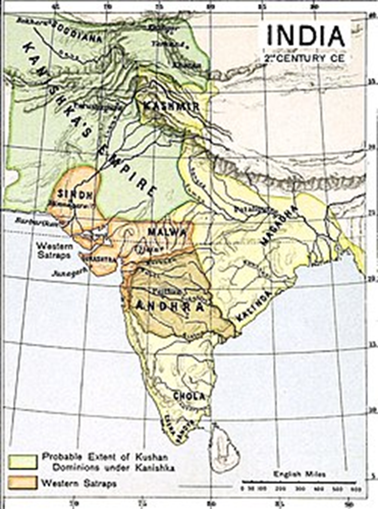

The Kushana Dynasty (1st century CE to 4th century CE), founded by the Buddhist king Kanishka, was a huge empire encompassing Afghanistan and northern India reaching Varanasi. Sanskrit, Greek, and Bactrian were the official languages and people practised Buddhism, Hinduism, and Zoroastrianism. After the fragmentation of the Kushana Kingdom, the Guptas (3rd century CE to 543 CE) covered much of the Indian sub-continent.

The Guptas after the Kushanas

In the South, the Satavahanas (2nd century BCE to 3nd century CE), the Chalukyas (543 CE to 753 CE), and the successive Sangama, Saluva, Tuluva, and Aravidu dynasties of the Vijayanagara kingdom (1336 CE to 1646 CE) ruled across major areas of present day central states — Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and extending up to Gujarat. Multiple languages were spokenand multiple faiths followed, and that was the norm. Arts, architecture, public administration, and trade flowered maximally in the Vijayanagara Kingdom, its most popular king being Krishnadevaraya. The popular languages were Kannada and Telugu with Sanskrit as the official language.

The Satavahanas

The Vijayanagara Kingdom

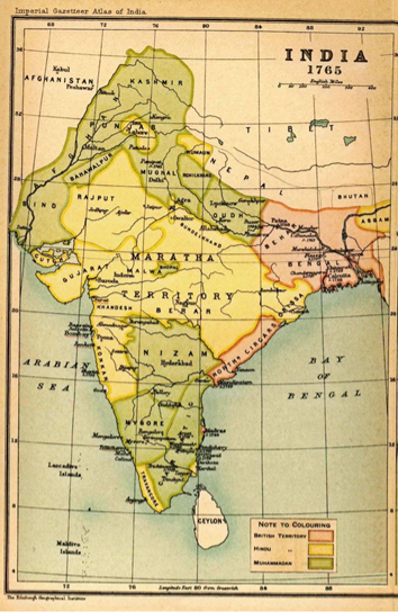

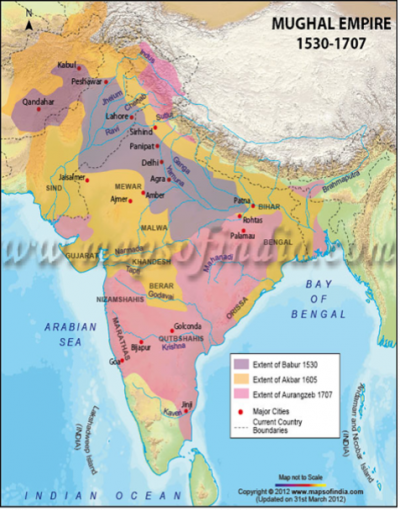

After the smaller kingdoms, the Mughal Empire starting with Babur (1526) was also an attempt at pan-Indian unification. Its peak extent was an area of 4,000,000 square kilometres. Persian, Urdu, and Arabic were the official languages. After its peak in early 18th century, it started declining after the death of Aurangzeb’s son, Bahadur Shah I, when it lost large tracts of land to the Marathas. Unfortunately, the only history drilled into school children in Indian is an account of the three- century Mughal period.

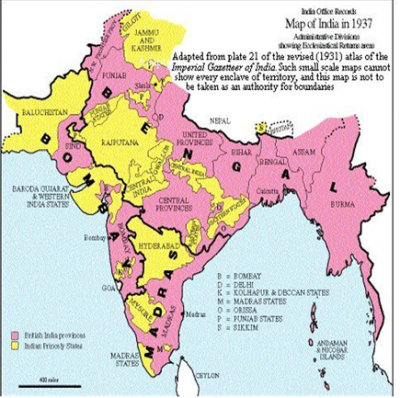

The Maratha Empire (1674-1818; area 2,50,000 square kilometres at its peak) stretched from Tamil Nadu to modern day Peshawar in the North and to the Bengal region in the east. Under pressure from the Marathas and the English radiating out from Bengal, the Mughal Empire finally collapsed in 1857 when Bahadur Shah Zafar lost to the British. India officially became a British Colony. The British Raj included two-thirds of modern India, and the rest one third were states ruled by princes.

Despite political changes, shifting boundaries, and expansions based on royal policies and ambitions, the idea of a separate and whole Bharatavarsha existed. The wars were fought on principles of not killing ordinary citizens, not destroying agricultural lands, not taking captive slaves, and not bringing down religious or educational structures. Most of the state structures remained intact during the wars. People moved freely across the kingdoms in their pilgrimages, trade, or studies. The sacred geography, Sanskrit, and the scriptures helped certainly in keeping a national consciousness largely intact which transcended the political boundaries.

The Story of other Nation States

If the legitimacy of current nation-states is on centuries of common continuous political rule over the same geographical boundary and inhabited by the same people, then no country on the planet meets these criteria as Sankrant Sanu elegantly demonstrates in his essay. Some academics concur with British authorities on their primary role of giving a political unity to India. What then of the United Kingdom itself in the present form? The Act of Union in 1702 brought together England and Scotland; in 1801, England joined Ireland; the latter split into Northern (mainly Protestant) and Southern Ireland (mainly Catholic and a separate country now) in 1922.

North America was a polyglot of cultures existing for thousands of years before Christopher Columbus “discovered” America and started bringing Europeans. There was a large-scale extermination of the local tribes and occupation of lands by the European settlers. Just three hundred years ago, the British colonies occupied less than 10 percent of the current geographical areas. Only a few states on the East Coast initiated the separation of America from the British in 1776. Texas and California become part of the US as late as 1845. The United States is barely 100 years old as a state; and as a political entity, about 250 years, with many annexations and a civil war in between.

The Aztec Empire, an alliance of three city-states, ruled the area in and around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until the Spanish defeated them in 1521. Importantly, it followed a polytheistic tradition with a diverse pantheon of deities. Christianity soon replaced this remarkable pagan tradition; today, more than 95 percent of Mexicans are Christians. Mexicans pride themselves with the Aztec connection but without any connections to the pagan traditional past.

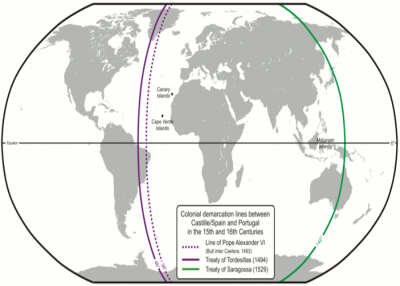

South America dramatically took shape to the present position due to colonial exploitation and European powers drawing the boundaries. In the pre-Columbian era (before Columbus entered in 1492), the large land was a huge mix of many cultures and civilizations — Norte Chico, Chavín, Moche, Nazca, Tiwanaku, Huari, Chimus, Incas (1438 to 1533), and so on. Then Spain and Portugal came, armed with the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), and approved by the Pope. This “authorized by the Pope” treaty divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire (eastern lands) and the Spanish Empire (western lands), along a meridian 370 leagues off the west coast of Africa. The Catholic monarchs attempted to stop the Portuguese advance in Asia by The Treaty of Saragossa in 1529 dividing the other side of the world too. The Protestant nations and Catholic France did not recognise the treaty as they went on their own adventures. Gradual independence after several wars and destruction by local populations resulted in the present political divisions in South America.

For thousands of years, Australia was inhabited by local Aborigines till the Dutch arrived in early 17th century and called it New Holland. Great Britain claimed the eastern half of Australia in 1770. The continent country gained independence from the UK in 1901. The indigenous population, economically and socially deprived, now constitute about 3.3 percent of the total population.

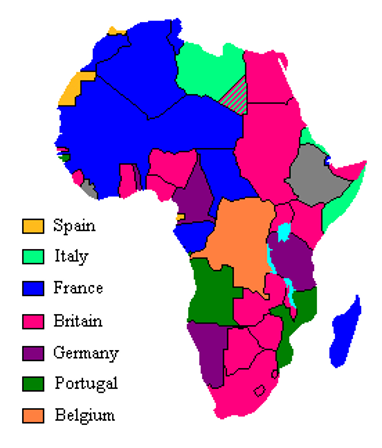

One of the direct consequences of the nations and nationalism, which Indian thinkers like Aurobindo and Tagore did not fail to notice, was the colonial and missionary adventures of European nations, especially to Africa, which included an extensive slave trade. The Scramble for Africa, or the Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, occupation, division, and colonization of African territory by European powers during a short period of New Imperialism between 1881 and 1914.

Between 1870 to 1914, European control over the African continent increased from 10 percent to almost 90 percent! The Berlin Conference of 1884, which regulated European colonization and trade in Africa, was the final point of the Scramble for Africa, where the European nations decided a systematic partitioning of Africa to avoid conflict between themselves. There were no African representations in this process of course.

Africa in 1914

Africa at Present

The Treaties of Spain and Portugal with the Pope’s Sanction to Occupy Foreign Lands

South America 1453

South America 1789

South America at Present

Conclusion

Sri Aurobindo (The Incarnate Word) wrote:

“The whole basis of the Indian mind is its spiritual and inward turn. There is a tendency, therefore, to create whatever it had to create from within outward. It could not begin with a political unification effected by an external rule, and this cannot be called a mistake or a proof of an unpractical turn. And even if an outward imperial unity had been founded—like that of the Roman world — it might not have endured. After all, the spiritual and cultural is the only enduring unity and, though the positive western mind may be unwilling to understand or concede this, the proofs are written across the pages of history. In the nature of things spiritual unity is a large and flexible thing and does not insist like the political and external on centralisation and uniformity of an imperial state…The Vedic Rishis were not blind to the need of a political unification, which they subsumed under the ideal of the cakravartin, of which the Aswamedha and Rajasuya sacrifices were the outward symbol. Not a destructive and predatory invasion, but a hegemony or confederacy under an imperial head would be the nearest western analogy to the conception they sought to impose on the minds of the people”.

The British allegedly consolidated India politically to some extent, but they were not the first to do so. The British divided us politically into two countries using religion, caused social disruptions by their caste-system narratives and pernicious Aryan theory frameworks, converted our traditions (with a phenomenal tolerance to differences) into proper religions of the Abrahamic mould (characterized by differences and mutual intolerances), stripped us economically, dragged us into two world wars where we had no stakes, caused the worst famines in Bengal influenced by their Malthusian ideas, fed their industrialization by raw material produced in India, made India a market for their finished products, destroyed agriculture by converting large tracts of land for cash crops or for their opium trade, levied heavy taxes, but apologists credit the British for uniting India as “one-nation” politically!

Typical of Indologists across centuries, and till date, believed that Indian civilization reached its peak only under Chandragupta and Asoka Maurya (3rd century BCE — 4th century BCE), the Gupta emperors (4th century CE — 5th century CE), and the last great imperial ruler — Harsha (seventh century)! Vincent Smith (1848-1920) wrote: “Harsha’s death loosened the bonds which restrained the disruptive forces always ready to operate in India, and allowed them to produce their natural result, a medley of petty states, with ever-varying boundaries, and engaged in unceasing internecine war”. For Smith, India had a “natural disunity” and a centralized authoritarian rule imposed from outside was the only way to unity. Any amount of Indological scholarship does not refute this position even today despite glaring evidence to the contrary.

Colonial scholarship had to claim that India had declined to almost barbaric levels with nothing by way of literature, arts, religion, or the sciences. The architecture, though grudgingly acknowledged “grand,” had “aesthetic issues and controversies”. Compared with other civilizations, India appeared to be singularly lacking in political unity and, therefore, in history. This happened because India was a land dominated by “imagination rather than reason” (Hegel) or because of an exotic institution of caste (James Mill).

The colonialists had a clear mission in showing the political disunity of India, but why do we need to repeat this story of “political disunity” in India today? “Colonial consciousness” pervades India and Indian leaders and intellectuals. Did we really need political unity as required by the West? As a nation of people with diversity and multi-cultural pluralism ingrained in nationalistic thought, the political state came much later. Our diversity and acceptance of diversity define civilizational India, not the idea of political unity. Crossing kingdoms did not amount to treason for us. Invasions and colonial conquests took place because the invaders did not have such noble values. For them diversity, pluralism, and a decentralised polity were a weakness to conquer politically by force; for us it was a strength which keeps us united despite all attacks. We are the last surviving and the most ancient pagan civilization despite everything which happened in the last thousand years.

Sovereign independent states became the international norm due to the peculiar circumstances of European history. The consequences have been nationalism, colonialism, and world wars leading to global plunder and extermination of local populations. Our nationhood was never a homogenization implemented from the top. States, nations, sovereignty, and nationalism are clearly rooted in European history and Christian theology. Our “nationalism” was about absorption and not invasion. What do we try to protect when we talk of nationalism? It is the multitude of traditions and cultures existing in harmony in Indian society.

Standard western theories (Hobsbawm, Gellner, Anderson) trace the origins of nations in institutional, economic, and technological transformations. These scholars only enlighten us on the emergence of modern “governmentality” to attain greater efficacy but not nations and nationalism, says Saumya Dey (Narrativizing Bharatavarsha). Dey argues that the Greeks, English, and the French were an ancient “felt community” much before the arrival of printing presses, democracy, or industrialization. Dey says that the modern, western term “nation” does not do justice to India’s expression of oneness.

India is an ancient felt community because it does not emerge through deliberate cultural or linguistic systematization. It functions and forms through a sense of belonging to the land, and disseminated through symbols. This process manifests itself as “culture,” autonomous of the state. Thus, people could belong to the same set of meanings and land by perceiving the same symbols as a great unity even with different languages. Bharatavarsha has been a “felt community” for thousands of years.

The swastika, the lotus, the devatas of temples, the tirthas, Sanskrit language as a bearer of meanings par excellence, of both practical and spiritual relevance, are examples of these interconnected symbols. They evoke and collectively assimilate Indians into the same matrix of meanings. Dey concludes that Bharat/Bharata views itself as a cultural unit with a federation of sub-identities preserving their individuality and equally contributing to the evolution of a common culture. In other words, there was an underlying and fundamental cultural unity in all the diversity.

Radhakumud Mookerji (The Fundamental Unity of India) relied on the Vedas and Puranas as historical documents for a common shared geography in the public consciousness and holding of some constituents as objects of veneration and pilgrimage. Both the “foci and loci” of religious and cultural identities lay within the same sacred geography which was proof of civilizational unity for Mookerji.

India is a dynamic cauldron of many physical, spiritual, and social components: a huge number of sampradayas or paramparas. Thousands of texts describe all these apart from the sciences, arts, grammar, drama, dance, devas, devis, stories, and so on. How does one make sense of all these? The traditions intricately link to each other with common elements in their descriptions, and yet may have completely different approaches. They may not agree with each other and yet accept the other as not false. Traditions may come together to evolve a new tradition.

The absolutist philosophies of monotheism or Communism would be the stratagems for nations in the modern framework. For India, in a very different cultural milieu, this can never work. We were not comfortable with the idea of religion splitting us. India could absorb a multitude of religions without any issues so long as they subscribed to the idea of a multi-traditional land. For reasons we do not understand, even Abrahamic religions took the form of traditions in our country. In this paradigm of mixing traditions without friction, there would be more space to understand and encourage the syncretism with Abrahamic faiths. A mix can happen without a threat to personal belief and faith.

Languages as the basis for the reorganization of states is an artificial and forcible application of one language-one nation theory which can be traced to Europe. Tagore was clear that political organisation comes secondary in the Indian concept existing only for the self-preservation of a cultural ethos allowing radically different thoughts and ways of living in a single geographical area without trying to kill or convert. Political boundaries never mattered historically where pluralism and multi-culturalism were the norm. It was not a homogenization of the many which the west is so fond of.

In Indian kingdoms, multiple languages were the norm. Multiple languages under the Cholas, the Vijayanagara kings, and the Marathas did not give rise to demand for states on linguistic basis. However, post-independence, language has played a key and distressing role in Indian politics. The anti-Hindi agitation, the reorganisation of states on a linguistic basis, the fights for a classical language status, the Hindi-Urdu divide — all worked together to bring a cultural homogenization to groups of people when none previously existed. Ashwin Kumar has dealt elegantly with language as a means for nationalism and its inappropriateness in the Indian context in his wonderful book, “Nationalism, Language, and Identity in India”. A forced homogenization on language or religion thus leads to a dangerous situation when the differences which erupt become proof positive to say that “India is not one nation”. This is the danger of using western theories to look at India.

This is what defines India as a nation: a group of people in a land which allows traditions with multiple differences to co-exist. Our nationalism precisely protects the ethos of multi-culturalism. Western ideas to mould political unity by homogenization using language or common economic ideals do not simply apply to India. Our economies, starting locally and spreading centrifugally, were traditionally the reverse of the central model adopted by most modern states.

Sanatana Dharma is about harmony in a centrifugal mode starting from the individual self and expanding to wider circles of family, society, and the state. The key concept of dharma which asks us to sacrifice the lower for the sake of the higher in times of conflict is almost intuitive in people calling themselves Indians. The modern, western ideas are increasingly about the autonomous individual. Theories of nationalism are western paradigms to build and understand nations. The facts of India do not match the theories, but typically, the theories stay intact while denying the data. Instead of taking new approaches, the most convenient way for lazy scholarship is to say “India was never a nation and became one after the British came”. There is an alternative story of India.

Readings and References

- The Mahabharata: Book 6, Section 9: Bhishma Parva, Jamvu-khanda Nirmana Parva by Kisari Mohan Ganguli (https://sacred-texts.com/hin/m06/m06009.htm)

- India’s Culture and India’s Future, by Michel Danino

- Nationalism in India, by Rabindranath Tagore (https://tagoreweb.in/Essays/nationalism-216/nationalism-in-india-2626)

- Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo (https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/14/indian-polity-iv)

- Blood and Soil (https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/nazi-germany/blood-and-soil/)

- Blood and Soil (https://www.nature.com/articles/141621a0.pdf) A very interesting article of 1938 explaining the dangers of racism

- “Nations” or “States” an Attempt at Definition, by Peter Ravn Rasmussen (https://archive.globalpolicy.org/nations/nation/2001/0720definition.htm)

- Peoples and Nations, by SN Balagangadhara (https://www.hipkapi.com/2023/03/29/peoples-and-nations/)

- India: A Sacred Geography, by Diana L Eck

- http://ancientvoice.wikidot.com/bharatavarsha. A great resource for ancient India designed by a former ISRO scientist Jijith Nandamuri Ravi. It is a one stop place for many of our scriptures like the Vedas and Itihaasas along with a rich availability of many useful maps related to ancient India.

- The Fundamental Unity of India, by Radha Kumud Mookerji

- Nationalism, Language, and Identity in India: Measures of Community, by A P Ashwin Kumar

- Swami Vivekananda on India as a Nation, by Amit Kumar Raul (https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol9-issue3/E0932528.pdf)

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nationalism/ A good compact resource for theories of nationalism

- A general resource to understand the religious wars of Europe which ultimately laid the basis of nation-state-sovereignty (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_wars_of_religion)

- Aryas of Aryavarta, by Rekha Rao (https://www.indiafacts.org.in/aryas-of-aryavarta/)

- Why India Is A Nation, by Sankrant Sanu (https://sankrant.org/2003/10/why-india-is-a-nation/)

- Narrativizing Bhāratvarṣa & Other Essays, by Saumya Dey

- The Notion of India, by Subhash Kak (https://www.academia.edu/49215115/The_Notion_of_India)