The Kashmir Files: Descent into Darkness or a Ray of Hope?

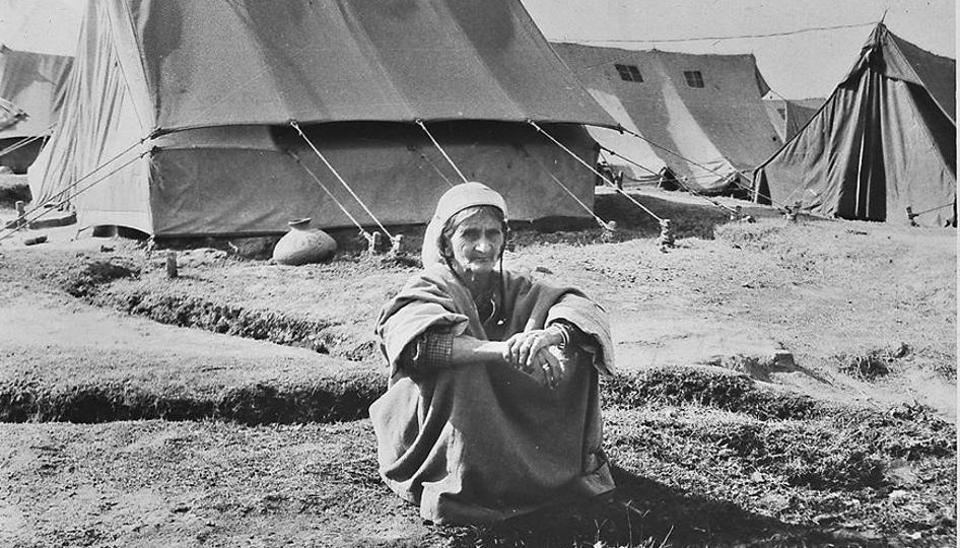

(Image courtesy: hindustantimes.com)

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”

— George Santayana (1)

The release of The Kashmir Files in March 2022 was followed by the publication of a series of articles denouncing the film. The reasons put forth for this censure varied from that of impugnation to the charge that the film would act as a catalyst in fostering an environment of hate.

One such piece, by Debashish Roy Chowdhury, was published in TIME magazine.

Chowdhury roots for a proper evaluation of the causes of conflict and for reconciliation but refuses to acknowledge the role which The Kashmir Files may play in the process of healing. After the end of apartheid in South Africa, a “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” was set up in 1995, under a law passed by the country’s new parliament. The key aim of this commission was to promote reconciliation among the victims and forgiveness of perpetrators of apartheid by the full disclosure of truth. It took the testimony of nearly 21,000 victims, two thousand of whom appeared in public hearings (2).

Any meaningful reconciliation in Kashmir can take place only after the truth is told. What is the truth of Kashmiri Pandits? What historical memories does this displaced community carry? Let us see.

In his monograph “Paradise Lost,” Professor K L Bhan records seven exoduses of Kashmiri Pandits from Kashmir (3). The first Muslim ruler of Kashmir was Rinchana, who hailed from Ladakh and had embraced Islam. He assumed the title of Sultan Sadr-ud-Din. A few decades later, during the reign of Qutub-ud-Din (1373-1389 CE), Sayyid Ali Hamdani came to Kashmir (4). His book “Zakirat Ul Mulk” finds special mention by many historians (5). In it, he recommended that subjects under Muslim rule be divided into two categories, Muslims and Kafirs, their respective rights differing according to their religion. For dealing with zimmis/dhimmis (non-Muslims living in a region overrun by Muslims and given protected status to retain their original faith) Sayyid Ali gave a separate mandate to the Sultans. It comprised twenty rules, which Sayyid Ali stated were based on the agreement between Caliph Umar and the newly conquered Arab nations. Some of the terms were – a bar on the construction of temples, non-Muslims to accord three days of hospitality to a visiting Muslim, a non-Muslim should not imitate the dress of Muslims, etc (6). These Islamic practices came to be adopted rather strictly.

The next ruler, Sultan Sikander (1389-1413 CE), earned infamy and came to be known as “But-Shikan,” destroyer of idols. He reportedly tried to pull down the famous Martand Temple but gave up the effort. Hindus were subjected to jizya (Islamic tax on non-Muslims) and forbidden to apply tilak on their foreheads (4). The first exodus of Kashmiri Pandits occurred during his reign.

Moving forward, during the reign of Sultan Fateh Shah (1489 CE), his minister for nine years, Musa Raina, a Shia, terrorized Hindus, imposed jizya, and destroyed their temples. The Chak rule in Kashmir commenced in 1554 CE. Ghazi Khan, the first Chak ruler, tyrannized Hindus forcing them to become Shias (7). The second exodus of Kashmiri Pandits occurred during this period.

After Kashmir fell into the hands of the Mughals, Iftikhar Khan was appointed as the Governor of Kashmir in the early-1670s. Aurangzeb was the Mughal Emperor at that time. Kashmiri Pandits complained that Iftikhar Khan was trying to forcibly convert them to Islam. He was also seizing Pandit women and handing them over as gifts to Muslim harems. Pandits approached Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh Guru, Tegh Bahadur, who told them to convey to the Mughal emperor that they would readily embrace Islam if the Guru could first be converted. Guru Tegh Bahadur refused and was beheaded (8). This led to the third exodus of Kashmiri Pandits.

In 1753, Kashmir came under the rule of Durranis from Afghanistan. It was largely a period of brutal tyranny. Pandits were forced to grow beards. Under one of the governors, the practice was to tie them up in grass sacks and sink them in the Dal Lake (in Srinagar). Many others were killed or converted to Islam. Some also fled (9). This was the fourth exodus of Kashmiri Pandits.

Kashmir passed into Sikh hands in 1819. The conclusion of the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846, following the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839 and the first Anglo-Sikh war in 1845-46, heralded the establishment of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir under the suzerainty of the British Indian Empire (10). In July 1931, Abdul Qadeer, the cook of a European military officer, was to be tried in Srinagar. He was charged under sections 124-A (sedition) and 153-A (promoting disharmony) of the Indian Penal Code. To avert a public demonstration/rioting, the Chief Justice ordered that the trial take place within the precincts of the Central Jail, and not in the courthouse. The hearing was held on July 13. A mob stormed the jail. The District Magistrate declared the crowd to be an unlawful assembly and ordered the police to open fire. As a reaction, there was a frenzy of violence against Kashmiri Pandits (11). What followed was the fifth exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. Next, the policies followed by the Government of Jammu and Kashmir in independent India, post-1947, led to another slow exodus from the 1950s to the 1980s. The January 1990 events depicted in the film were the immediate cause of the seventh exodus.

By any standard of natural justice, a community that has suffered so much has a right to tell its story, and humanity demands that we hear this story with empathy. Chowdhury claims that the film’s graphic description of the violence wrought on Hindus is aggravating religious discord. If that were so, what would Chowdhury have to say of the review in TIME magazine of the 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave? The review mentions that in the movie, plantation owners poke and stroke the bodies of their slaves, appraising them like horseflesh. Its conclusion is that the film is a raw, horrifying, and essential document about the brutality and inhumanity of slavery (12). Will Chowdhury similarly insinuate that 12 Years a Slave contributed to aggravating racial discord in the United States? Or is it that for TIME magazine, 12 Years a Slave is a raw and essential document, but The Kashmir Files is not, as histories of some matter more than those of others?

It is quite evident that Chowdhury is not a fan of what he derisively refers to as “Hindu nationalism”. He is certainly entitled to his political preferences. What is unfortunate though is that his disapproval of Prime Minister Narendra Modi leads him to repeatedly make errors of omission. He alleges that PM Modi heavily championed the movie. What Chowdhury omits to say is that PM Modi in his statement encouraged criticism of the film on factual and artistic grounds. He also invited those who had reservations about the film to make another film in response so that there could be a healthy discussion in the public domain. What PM Modi was not appreciative of was the attempt of an entire ecosystem to discredit the film by asserting that such a film should never have been made (13). As a journalist, does Chowdhury endorse freedom of expression and debate, or does he lean towards selective censorship?

Chowdhury expresses concern that social media was flooded with videos of hate speeches and calls for the slaughter of Muslims after the film was released. He does not corroborate these claims with any factual data. What he also fails to mention is that there are social media posts every other day calling for the elimination of Hindu Kafirs (non-believers). See here and here. A more balanced and objective observation by Chowdhury would have included a condemnation of any call for violence by anyone on social media.

Chowdhury goes on to allege that there is a climate of growing intolerance, where exclusion and marginalization of Muslims have become mainstream. If Chowdhury has any constructive suggestions on how this supposed marginalization of Muslims can be addressed, it will be more than welcome. At the same time, Chowdhury might also want to pay attention to what was recently highlighted by Arif Mohammed Khan, the Governor of Kerala. The Governor, a Muslim, has quoted a Pakistani scholar, Javed Gamdi, as having said that in madrasas, children are taught that non-Muslims are born to be ruled by Muslims; that any non-Islamic government is illegitimate; and such governance should be reversed as soon as possible. Gamdi had made an urgent plea for educational reform in madrasas saying that as long as this kind of education, perpetrating hate against non-Muslims, continues it would not be possible to establish peace in the world (14).

Chowdhury is also dismissive of the film’s claim that there was a genocide of Pandits in the 1990s. Perhaps Chowdhury also has facts to support his position. But these certainly do not form a part of his article. The United Nations Genocide Convention defines genocide as any act committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group. The acts committed include physically killing members of the group and causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group (15). Film-maker Vivek Agnihotri recorded interviews with more than seven hundred victimized Kashmiri Pandits while researching for the film (16). Perhaps a “truth and reconciliation commission” could be set up where these interviews are admissible as evidence (along with other testimonies) and which can help determine whether the trauma which the Kashmiri Pandits lived through in the 1990s qualifies as “genocide” in accordance with the Articles of the UN Convention.

Chowdhury is also skeptical of the claim in the film that the horrors visited upon Kashmiri Pandits were hushed up. Has he overlooked the fact that when Kashmiri Pandits petitioned the National Human Rights Commission in 1995 asking that authorities extend them facilities and rights by virtue of their internal displacement, the Government of India’s argument before the Commission was that the word “migrant” was a more appropriate description of the status of the Kashmiri Pandits (17)? Would a more just approach evaluated the case of the Kashmiri Pandits based on the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) guidelines for defining and identifying IDPs (Internally Displaced People)? As justice should not only be done but also seen to be done, these findings ought to have been publicized widely.

Several blockbuster films have been made in India against the backdrop of 1990’s Kashmir. Roja (1992), Mission Kashmir (2000), Fanaa (2006) and Haider (2014) are a few notable ones. The tragedy which befell upon Kashmiri Pandits in January 1990 (and continues to this day) is not interwoven into the storyline of any of these films. Was it a hushing-up, as highlighting the plight of Kashmiri Pandits is against the dominant narrative or were the screenwriters of all these films simply interested in exercising their artistic freedom (which they are certainly entitled to)? It would have been illuminating if Chowdhury had weighed in with his thoughts on these films and their hushing up of the “inconvenient”.

Chowdhury is not pleased that the “Hindu right” disparages “liberal media” as “presstitutes”. What Chowdhury omits to mention is that the opponents of PM Modi often denigrate those sections of the media which do not assail PM Modi all the time as a fascist, as “Godi Media” (the media which sits in the lap of PM Modi).

Chowdhury is also extremely critical of Muslim boys being shown as demonic. What he omits to mention is that children have been forced to serve as soldiers in several armed conflicts around the world. For instance, a 2021 Human Rights Watch report describes how Al Shabab, an Islamic State-linked group in Northern Mozambique kidnapped boys as young as twelve and forced them to fight against government forces (18). Perhaps, for Chowdhury, scenes from the 2006 film Blood Diamond where child soldiers in Sierra Leone were shown committing violent acts were a demonic portrayal rather than cinematic depiction of a harsh reality. As for Kashmir, the fact is that in the years leading to 1990, seeds of fundamentalism and separatism were being planted in young minds, and the young were paid and hired to commit violence. Children in the Jama’at-i-Islami run schools and madrasas were being brainwashed with anti-Hindu propaganda. A poem prescribed for Class III students read as:

Little Children, be very calm

I will tell you what is Islam

You may be very few and without army

But you must fight for Islam (19)

What we read and are taught has a significant bearing on what we become. What conduct could one expect from young students studying in these schools and madrasas? Chowdhury is deliberately mum on these matters.

He is also scornful of the term “Love Jihad,” which he says is a trope employed by the Bharatiya Janata Party. What Chowdhury misses is that the term “Love Jihad” formed part of the 2009 Kerala High Court order in Shahan Sha A vs State of Kerala (20). The High Court had directed the Central and State Governments to enquire into “Love Jihad” or “Romeo Jihad,” a campaign propagated by Muslim organizations to convert girls into Islam under the pretext of love (21). Some of the slogans broadcast from loudspeakers in Kashmir on the night of January 19, 1990, were — “Anyone wanting to live in Kashmir will have to convert to Islam,” and “We will turn Kashmir into Pakistan along with Kashmiri Pandit women but without their men folk” (22).

Chowdhury refers to a viral video where an agitated member of the audience can be seen urging Hindu men to preserve their religion by marrying Muslim girls. While being rightly critical of calls like these, he maintains a curious silence on the terror Kashmiri Pandit women would have felt when loudspeakers in Kashmir were blaring with slogans asking for Kashmiri Pandits to leave the Valley without their women.

Chowdhury mentions that both Hindu and Muslim women trapped in the war zone of Kashmir have faced sexual violence by militants as well as security forces. The detail that he misses here is that Islamist militants have often claimed a theological sanction for their acts of violence. A recent article in The Diplomat highlighted that several radical political leaders of Kashmir had exhorted women to give their bodies to men who fight the “Holy war”. There were also women-led movements like Dukhtaran-e-Millat which called for harsh Shariah codes to be implemented and to mete out harsh punishment to women for not sticking to dress codes (23). In contrast, the few and far-between transgressions by security forces have largely been because of errant individuals. Needless to say, once their crimes are proven, these transgressors have faced punishment and justice.

Chowdhury claims that Modi’s need to portray himself as a Hindu “strongman” dominating Muslims was the motivation behind his stripping of Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir of its partial and conditional autonomy. While he imputes motives to Modi without substantiation, he omits to mention the fact that Article 370 of the Indian Constitution which gave Jammu & Kashmir special status, was labelled as “Temporary provisions with respect to the State of Jammu and Kashmir”. Also, there was a provision in the Article itself (Article 370.3) that provided a mechanism for the article to be made inoperative (24). Government actions are subject to judicial review, and petitions challenging the changes made to Article 370 have been listed to be heard by a five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court of India (25). The system of checks and balances is in place and is functioning in India, as it ought to.

Chowdhury should also take note that under Article 370, a Presidential Order was issued in 1954. Article 35A was added to the Indian Constitution that empowered the Jammu & Kashmir state legislature to define “permanent residents” of the state and provide special rights and privileges to them (26). How did this play out? A woman who was a “permanent resident” of the state would lose her rights to the ancestral property if she married outside the state. Thousands of descendants of Valmikis (Dalits) who were brought in from Punjab as government sweepers in 1957 were never allowed to get any government jobs other than that of sweepers (27). We presume that Chowdhury would be staunchly against such discrimination. Will he welcome Article 35A being made inoperative by virtue of the revocation of the special status granted to Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370?

Chowdhury writes about a lock-down in the region and of months-long information blockade. He fails to mention how agitated “conflict entrepreneurs,” whose very lucrative political enterprises in Kashmir were staring at an early demise after the revocation of Article 370, would have been under extreme pressure to inflame passions in the Kashmir Valley. After the information blockade was lifted, the law-and-order situation registered a marked improvement. The Director General of Police for Jammu & Kashmir reported that incidents of stone pelting had dropped by 87% in 2020, compared to 2019, when the special status was revoked (28).

Chowdhury claims that Kashmir’s long struggle for secession helps validate the Hindu nationalist case that Muslims, with their extraterritorial loyalties are an existential threat to Hindus and the integrity of India. A factual question that arises is, what is the relationship between Islam and the sovereign state? The Quranic Concept of War authored by Brigadier S K Malik was first published in Lahore in 1979. The foreword to the book was penned by Zia-ul-Haq, then Army Chief and President of Pakistan. In his 2006 review of the book, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph C. Myres of the United States Army opined that it is like other works such as Sayyid Qutub’s Milestones — a statement about the role and the duty of Islam to fulfill its mandate as revealed by Allah to Prophet Muhammad. The preface to the book was written by Allah B. K. Brohi, a well-known lawyer and briefly Attorney General for Pakistan. Brohi acknowledged that in modern society, maintenance of international order proceeds on the premise of sovereign equality of “nation-states,” all of which have a territorial aspect. He posited that the idea of the Ummah of the Prophet of Islam is incapable of being realized within the framework of territorial states. From this vantage point, the world is viewed as being polarized between the “world of Islam” and the “world of war”. His conclusion was that Islam did not subscribe to the concept of the territorial state (29).

Can people with diametrically opposite set of values live harmoniously in the same country, under the same set of laws? In the European context, British Prime Minister David Cameron had declared at the Munich Security Conference in February 2011 that under the doctrine of state multiculturalism, different cultures had been encouraged to live separate lives, apart from each other, and apart from the mainstream. He added that certain segregated communities had behaved in ways that ran completely counter to British values (30). To address this, Bassam Tibi, a German-Arab academic propounded the concept of “Leitkultur” (leading culture or core culture) in the late-1990s. He argued that while people of different backgrounds in Europe may not be united by a common heritage, all should at least endorse certain core concepts like modernity, democracy, and so on (31). What exactly is meant by “Leitkultur” was still being debated well into 2017 in Germany, suggesting that this is by no means a settled question (32).

In the Indian context, Muslim Rashtriya Manch, launched at the initiative of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in 2002, tries to drive home the message at all forums that Muslims and Hindus share the same ancestors, culture, and motherland. There is thus no scope for confrontation. The way forward is neither appeasement nor separatism but nationalism by realizing the spirit and soul of India (33). Chowdhury is free to criticize this initiative with all the strength at his command if alongside he can also provide a creative solution to the vexed issue of successfully assimilating a worldview that does not endorse the concept of a territorial state within the framework of a sovereign state.

Chaudhary alleges the proliferation of Islamophobia in Bollywood with the release of period films featuring noble Hindus resisting devilish rulers. He terms this a revisionist trend and weaponization of popular opinion. The key question on which Chowdhury maintains a cryptic silence is, what are the historical facts? Long before the term “Islamophobia” became a political tool to undermine the world’s efforts to deal with Islam-inspired violence and extremism, this is what the famous American historian Will Grant wrote in 1935: “The Islamic conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilisation is a precious good, whose delicate complex of order and freedom, culture and peace, can at any moment be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within” (34).

It is also true that for long after independence from the British in 1947, historiography in India was not in the service of truth but in the service of a certain ideology. For example, the West Bengal Board of Secondary Education issued instructions in 1989 that Muslim rule should never attract any criticism. Destruction of temples by Muslim rulers and invaders should not be mentioned (35).

Yes, in recent years there have been calls to revise history textbooks in India. Chowdhury would have made a positive contribution to this debate had he suggested that revisionism ought to be in line with historical evidence while helping the students of history to learn from the mistakes of the past. However, he merely criticizes the present exercise of revising history books that seeks to correct deliberate acts of omission and commission by politically compromised historians, without giving any consideration to historical facts.

Chowdhury expresses concern about the calls for genocide of Muslims, an assertion for which he does not provide any evidence. This, along with his downplaying of the fact that the sufferings of Kashmiri Hindus may genuinely constitute a case of “genocide,” makes one wonder whether his primary aim is to inform the readers or to propagate a certain narrative.

Chowdhury complains about what he labels “state-sanctioned religious hate” – sanctions imposed by states against the wearing of hijabs by Muslim girl children in public schools, and the opposition to public prayer where Muslim throngs shut down access to public roads, parks, and other spaces when they congregate to pray. What he omits to mention is that the restriction on hijabs was in the context of laying down a dress code in schools, a restriction which was upheld by the High Court of the State of Karnataka in March 2022 (36). Students are free to wear hijab in schools where the school uniform rules allow this. In 2018, Norway’s parliament overwhelmingly voted in favor of a ban on wearing burqas in schools. Was this also state-sanctioned hate (37)? In December 2021, the Chief Minister of Haryana publicly say that prayers should only be offered in mosques and not in public places (38). What would be Chowdhury’s take on Abu Dhabi police imposing a fine of 1,000 Dirhams on those praying on the side of the roads — state-sanctioned hate or an attempt to maintain order on the streets (39)?

Chowdhury concludes his tendentious piece with a rather bleak claim that The Kashmir Files marks a major milestone in India’s rapid descent into darkness, and that this marks India’s drift into the abyss of an illiberal future. Here, we end on a more optimistic note. For what is life without hope? The Kashmir Files marks the beginning of a genre of cinema in India which could become a means of catharsis for a traumatized people. It will hopefully lead to calls for a restorative justice program for the long-persecuted and ignored Kashmiri Pandits. From the darkness of strife rooted in religious ideologies which divide the world into two hostile camps of believers and non-believers, it may pave the way towards the light of peace and brotherhood, founded on natural human reason.

References and Links:

1. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/those-who-cannot-remember-past-are-condemned-repeat-it-george-santayana-life-reason-1905

2. Apartheid Museum. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

https://www.apartheidmuseum.org/exhibitions/the-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-trc

3. Ikashmir. Seven exoduses of Kashmiri Pandits

https://ikashmir.net/exodus/doc/exodus.pdf

4. Jagmohan, 2017. “My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir,” pg 48.

5. Kashmir Life. Kashmir’s Amir-e-Kabir days,

https://kashmirlife.net/kashmirs-amir-e-kabir-days-issue-08-vol-11-210429/

6. Abdullah, D (1991). “Religious Policy of the Sultans of Kashmir (1320-1586 AD)”, page 55, page 59, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/144508677.pdf

7. Pandit Anand Koul (1991). “The Kashmiri Pandit,” pg 50.

8. Pandit Anand Koul (1991). “The Kashmiri Pandit,” pg 51-53.

9. W R Lawrence (1895). “The Valley of Kashmir,” pg 197.

10. Treaty of Amritsar (1846), Wikipedia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Amritsar_(1846)

11. G S Raghavan (1931). “The Warning of Kashmir,” pg 86.

12. Richard Korliss, TIME. “12 Years a Slave: An Unflinching Take on the Great American Shame,”

https://entertainment.time.com/2013/10/18/12-years-a-slave-an-unflinching-take-on-the-great-american-shame/

13. “PM Modi on The Kashmir Files,” India Today,

https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/pm-modi-kashmir-files-entire-system-discredit-film-truth-1925602-2022-03-15

14. “Kerala Governor on Udaipur murder,” India Today,

https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/-hatred-taught-in-madrasas-results-in-such-incidents-kerala-guv-on-udaipur-murder-1969240-2022-07-01

15. United Nations. Office of Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect,

https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/genocide.shtml

16. Manish Chaurasia, “Here’s what went into making of The Kashmir Files,” India Today,

https://www.indiatoday.in/movies/bollywood/story/here-s-what-went-into-making-of-the-kashmiri-files-700-interviews-of-victims-5-000-hours-of-research-1925281-2022-03-14

17. K C Saha. “Rethinking the Guiding Principles: The Case of the Kashmiri Pandits,” Forced Migration Review,

https://www.fmreview.org/accountability-and-displacement/saha

18. Human Rights Watch (September 29, 2021). “Mozambique ISIS-linked group using child soldiers,”

https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/09/29/mozambique-isis-linked-group-using-child-soldiers

19. Jagmohan (2017). “My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir,” pg 175.

20. Indiankanoon. Shahan Sha A vs State of Kerala, December 9, 2009,

https://indiankanoon.org/doc/576406/

21. New Indian Express. “HC tells Centre, State to probe ‘Love Jihad’,”

https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/2009/oct/01/hc-tells-centre-state-to-probe-love-jihad-92609.html

22. Indian Defence Review. “Kashmiri Pandits offered three choices by Radical Islamists,”

http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/kashmiri-pandits-offered-three-choices-by-radical-islamists/

23. The Diplomat. “Rape and Silence in Kashmir’s Jihad,”

https://thediplomat.com/2022/02/rape-and-silence-in-kashmirs-jihad/

24. ISAS. “India Amends Article 370 — A Constitutional Perspective,”

https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/india-amends-article-370-a-constitutional-perspective/

25. India Today. “SC may hear pleas challenging abrogation of Article 370 after summer vacation,”

https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/pleas-challenging-abrogation-article-370-jammu-kashmir-urgent-supreme-court-cji-1941508-2022-04-25

26. Wikipedia. Article 35A of the Constitution of India,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Article_35A_of_the_Constitution_of_India

27. Daily Excelsior. “Revocation of Article 370, a step towards equality and dignity,”

https://www.dailyexcelsior.com/revocation-of-article-370-a-step-towards-equality-and-dignity/

28. Economic Times. “Stone-pelting incidents dropped in J&K dropped by 87.13% in 2020,”

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/stone-pelting-incidents-in-jk-dropped-by-87-13-in-2020-dgp/articleshow/80075744.cms

29. S.K. Malik (1992), “Quranic Concept of War,”

https://wolfpangloss.files.wordpress.com/2008/02/malik-quranic-concept-of-war.pdf

30. UK PM’s Speech at the Munich Security Conference,

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pms-speech-at-munich-security-conference

31. Leitkultur, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leitkultur

32. “German issues in a nutshell: ‘Leitkultur’- acceptance vs assimilation,” Deutsche Welle,

https://www.dw.com/en/german-issues-in-a-nutshell-leitkultur-acceptance-vs-assimilation/a-38850129

33. Muslim Rashtriya Manch, http://muslimrashtriyamanch.org/Encyc/2016/1/13/About-us.aspx

34. Will Durant (1935). “The Story of Civilization (Part One), Our Oriental Heritage,” pg 459

35. Arun Shourie (1998). “Eminent Historians: Their technology, Their Line, Their Fraud,” Loc 895, Kindle edition.

36. The Print. “Restriction on wearing hijab ‘reasonable’: Full text of Karnataka HC judgement upholding ban,”

https://theprint.in/judiciary/restriction-on-wearing-hijab-reasonable-full-text-of-karnataka-hc-judgement-upholding-ban/874034/

37. Independent. “Norway’s parliament votes to ban burqa in schools and universities,”

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/norway-burqa-ban-schools-universities-parliament-vote-niqab-latest-a8387826.html

38. The Hindu. “Prayer should be offered in mosques instead of public places, Haryana CM Manohar Lal Khattar,”

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/prayer-should-be-offered-in-mosques-or-idgahs-haryana-cm/article23792159.ece

39. Gulf News. “Praying on roads will invite a fine of Dh 1000,”

https://gulfnews.com/uae/transport/praying-on-side-of-roads-will-invite-a-fine-of-dh1000-1.2160991