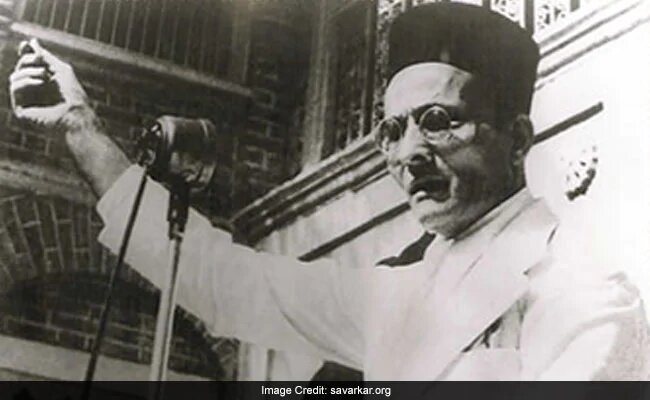

Veer Savarkar, the Unsung Hero of our Freedom Struggle

The 30th President of America, Calvin Coolidge, once said, “A nation that forgets its heroes will itself soon be forgotten,” and the quote aptly reflects the way Indians look at their own history. Indian history, as adumbrated by modern Indian historians, or at least the historians of the left/secular variety of them is more about twisting the past to suit their present ideological predilections than narrating as objectively and as carefully as possible what happened to Bharat that is India as the land and the people lived through the past millennia. As to the telling of recent events and of the contribution of men and women, what is clear and what is disheartening is the deliberate scrubbing of the tales of some men and women and their contribution to the building of the new India. Missing are the pages of nationalist heroes, who gave their lives to unshackle the country from colonial predators and who sought to dismantle the shibboleth of marauders. These are the heroes we have forgotten to read and to read about and revere. We are made to ignore or forget the glorious pages from Indian history by the well-entrenched Marxist academics who have taken over India’s academic institutions and who have installed their own cult members in the media, higher education administrations, and in political circles.

Sri Aurobindo Ghosh, Subhash Chandra Bose, and Veer Savarkar were some of the prominent freedom fighters whom the British despised for their revolutionary writing and armed struggle. It is unfortunate that whom the British despised and whom the British coddled are the very same set of men and women those post-independent Indian historians have embraced or demonized under the Nehruvian dispensation that has left India’s past – both recent and ancient — moth-eaten and partial. In recent years Savarkar’s thoughts and ideas have gained new currency but in popular memory and discourse Savarkar is still either maligned or ignored. A new generation of scholars and writers are seeking to correct this anomaly, and Vikram Sampath’s first volume on Savarkar, published in in 2019, is the most careful and well-written work. What, however, does not come as a surprise is how the big English newspapers and magazines, as well as academic journals have ignored Sampath’s work, even as it has become one of the most popular of works for Indian readers, despite its massive 600 page plus length.

The story of Savarkar and his nationalism goes back to his childhood days, when the three Chapekar brothers were hanged by the British government in the 1890’s for assassinating the brutal and arrogant “Plague Commissioner” W.C. Rand, under whose dictat the British police entered private homes, stripped, and examined people, including women, in public, and prevented people from moving out of Pune. This traumatized young Savarkar, who vowed before Goddess Durga that he would strive to ensure Bharat is independent from the clutches of foreign occupation.

Damodar Savarkar was a precocious boy – smart, well-read, a fine writer, and a born leader. The seeds of patriotism sown in his childhood days blossomed into a plant which would grow up like a big banyan tree. Savarkar travelled to England to study law on a scholarship, and his revolutionary activities started to take shape. Savarkar was arrested in London in 1910 on charges of inciting revolt and violence against the British and was sent back to India. What followed was a fifty-year sentence of rigorous imprisonment and transportation for life to the dreaded Cellular Jail in Andaman & Nicobar Islands.

Apart from being a true nationalist, one of the most striking qualities of Savarkar was his role as a historian: he was a creator of history as well and we can understand his life through his works.

In 1908, Savarkar at the young age of twenty-six, wrote his magnum opus The First War of Independence — 1857. The book is a step-by-step account of the uprising of Indians against the ruthless British and the author establishes the fact that the uprising was a “War of Independence” and not a mere “Sepoy Mutiny” as recorded by the British. The book became the inspiration for Indian revolutionaries.

‘My Transportation for Life’ by Savarkar was published in the weekly Kesari founded by Lokmanya Tilak as a series of articles during 1925-26, and Savarkar wrote about Hindu-Muslim relationship in his book Hindu Pad Padshahi, that while the historic enmity between Islamist aggression and Hindu resistance should not be projected into current normal Hindu-Muslim relations the lessons from history, however, should not be forgotten.

Savarkar was also emphatic and critical about the existing fault lines in Indian society. Savarkar was a fierce rationalist, and he rejected the birth-based varna system and built places of worship for people from all sections of society. Savarkar was a social reformer and worked against many issues ailing Hindu society like untouchability, divisions among Hindus based on caste, and proselytization of Hindus to Islam. He sought to find ways for his Hindu brethren to return to the Dharmic fold.

Savarkar gave the country the political philosophy of Hindutva and coined the term ‘Hindutva’ in his book Hindutva: Who Is a Hindu? (1923). Savarkar defined a Hindu as one who regarded the land of Bharat spread between the River Sindhu in the north and the ocean Sindhu Sagar/Indian Ocean in the south as their Pitrubhumi (fatherland) and Punyabhumi (holy land). In the age of political correctness, where a nation has come to be defined as people who through mutual consent build institutions to alter change and impact the world, there is a convenient and carefully constructed disregard for how others have formed nations – through religious identity, cultural history, tribal affiliations, and cultural identity. How this convenient and synthetically manufactured nation-state can be sustained despite group identities, cultural differences, past conflict is also conveniently ignored, or these differences are selectively picked to dismantle the very same conveniently manufactured state/nation. Thus, theses about modern states manufactured out of whole cloth get prime billing whereas what the likes of Savarkar sought to emphasize about nation-building is demonized and ridiculed. Anyway, the fact remains it was Savarkar who gave Hindutva a definitive shape and no doubt he remains the philosophical and intellectual fountainhead of Hindu political renaissance.

In the later years Savarkar wrote Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History to counter the then accepted view that India’s history was a saga of continuous slavery and defeats by external powers and regimes inimical to the culture of the land.

Savarkar’s name is now synonymous with courage, bravery, discipline, and patriotism though his detractors, the freeloaders who are the product of the Nehruvian system, seek to demonize him in a bid to soften if not remove the Hindu glue that holds Bharat or India together. True to his name, he was an inspiration to many revolutionaries of India’s freedom struggle, starting from Bhagat Singh, Dr Hedgewar who founded the RSS, Subhash Chandra Bose, and others. Savarkar, despite being labeled an atheist, was a true karma yogi who followed the principles of the Bhagavad Gita in his life.

If the British confined Savarkar’s spirit to the cells of Cellular Jail for over a decade, post-independence he was sought to be marginalized if not demonized by the left/secular Nehruvian cabals, which was in some ways a bigger ignominy and a harsher punishment. While Nehru and Gandhi, now lauded as the creators and founders of the new India, were housed in comfortable “jails” for their minor acts of self-sacrifice and weak attempts to dismantle the British Raj, Savarkar, who gave his all – family, health, comfort, career, life to rid India of the British — continues to be imprisoned in academic straightjackets and political purgatory. In fact, with the Bharatiya Janata Party in power over the past seven years, patriots like Savarkar are sought to be tarred a darker black by a deracinated, ignorant, fitful intelligentsia who have become even more fetishistic of the idea of a state created in a vacuum, and whose allegiance is first, foremost, and only to themselves alone – the disconnected individual. Paradoxically, this is the very same set of intellectuals who turn around and blame Hindus for their pursuit of the transcendental through the discarding of false and constraining identities.

We should always remember Veer Savarkar as a patriot who inspired countless Indians in troubled times. He unapologetically sought to unite Hindus under one flag and gave them an ideology that should inspire and guide them for generations to come. As Savarkar said, for a nation to survive it must reclaim its past. “The nation that has no consciousness of its past has no future,” he said, and it would only be fitting if we paid some attention now to the concept of the Hindu rashtra that Savarkar adumbrated and tweak it to deal with the dynamics of the new world where the fifty-six member nations of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation seek to bend the United Nations Organization to their will; or the old Christian nations of Europe and the new Christian nations of America seek to battle the Muslim nations or join hands with them to Christianize or Islamize the remaining non-Muslim, non-Christian nations of Asia; or where the Chinese seek to rule the world as the Middle Kingdom owning all.

Editor’s note: The coining of the term “Hindutva” is usually ascribed to Vinayak Damodar Savarkar who wrote about it in his pamphlet, “Essentials of Hindutva,” in 1923. Though it is true that Savarkar popularized Hindutva as a political and cultural concept, it was Chandranath Bose who first coined and used the term in his book, “Hindutva,” in 1914.