Intellectuals’ Labor Lost, Misdirected: Time to Regain Relevance

Running a democracy like India that abounds in thousand fault-lines is quite a task, something even many older Western industrial democracies will admit. If the latter is notionally characterized by debates, discussions and elections where rational men and women come to exercise their will by casting votes, the Indian cauldron of democracy survives on a political culture that defies the principle of free will and creates a template where people come to vote their caste (or religion). If one thought such political behavior is an anomaly and that our intelligentsia will be doing their bit to help people move away from such primordial ways of exercising democratic right, it is perhaps because one has not understood the contemporary intellectual labor and its expressions. A country that is home to a mind-boggling variety of languages, ethnicities, religions that constantly strive for articulation and assertion (not to mention their hurt feelings and marginalization), its democracy is loud, noisy and exhibitionist. What is equally true is that the emotional flare-ups and impatience do not simply define people and political leaders, but also characterize the intellectuals who contribute to that din.

The year 2020 was no different from earlier years in significant ways, except perhaps the fact that the pandemic forced most to confront the reality of physical and social distancing and the psychic dislocation thereof. That it changed people cutting across class, there is little doubt. But did it change our elite and alarmist intellectuals? Were they able to offer critiques of the new reality outside of the usual dissent stuff that characterized the pre-pandemic period, say the discourses around Article 370, the CAA and the aftermath? Did the pandemic engender any reflexivity and inwardness among them? The fact is that the intellectuals, who have already reduced intellectual labor to their mission of perpetuating dissent and mainstreaming agitation as the new definition of political awareness took upon themselves the responsibility of using the opportunity to enrage people. Thus, Ram Guha pandered to minority sentiment by identifying Hindu religious imagery in Modi’s COVID-19 speeches and believed that Modi’s use of Hindu imagery such as seven steps, diyas, Lakshman rekha and agni pariksha made India a Hindu majoritarian state. If you thought something civic and secular will be time for celebration, Neera Chandhoke questioned the spatial remaking of history in the construction of the new Parliament building, that she thought will “symbolise only the overweening desire for personal glory of a ruling class”.

Intellectuals as reactionaries:

To what extent Indian intellectuals created conditions for new ideas or reform is debatable. Throughout 2020, be it anti-CAA protests, the pandemic situation, the Ram Mandir verdict by the Supreme Court or the farmers’ agitation, they could never set the agenda. They only reacted to government policies and movements that other groups initiated (mostly interest groups and political parties) and tried to give it some intellectual credence, more as an after-thought or as a survival strategy. They contributed to the protests not because they knew the pathways for resolution, but due to an extreme suspicion of the government which they thought poses an existential threat to their trade. Blinded by a pathological hatred for Modi, combined with the realization of their powerlessness, they rode all kinds of anti-Modi bandwagon. During an interaction with British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, Arundhati Roy mourned that Modi government was making people forget the economic hardships and coronavirus by ratcheting up its cold Hindutva rhetoric. Ram Guha thought Modi government was misusing the pandemic to centralize its power.

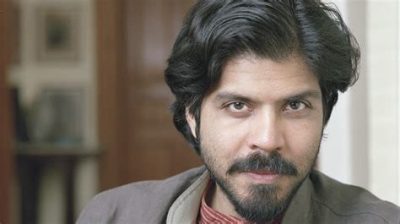

Ramachandra Guha, the seller of ideas for all seasons. Photo courtesy: Hindustan Times

It has been a remarkable fall for these intellectuals who absolved themselves of all social responsibilities and equated their vocation with Modi bashing. In the process, they created a republic of hatred where an ever-expanding politically and emotionally charged angry men are constantly demanding recognition and resources, and where any call for debate is a sign of weakness or a Hindutva ploy to silence dissent. No doubt, questioning the government in power has its merit and is often required for any positive change. But to believe that change can only be an effect of antagonism for the party in power is a stretch. In a postcolonial democracy like India, most social changes and reforms have been effected through legislation and if some reforms have not been realized, it is due to narrow political objectives or retaining vote banks. Thus, intellectuals of the secular Nehruvian type never bothered to show any alacrity in demanding women’s freedom within Islam or challenged minority persecution if the minority in question are Hindus or Sikhs (as in Jammu & Kashmir). This made them respond to repealing of Article 370 in ways that raised questions about what they actually want. During these situations, Modi phobia took precedence over their social responsibility and made them reactionaries; from being supposed role as catalysts of positive change, they became prophets of doom. So, when Pankaj Mishra calls Modi an evil genius, you see this principle at work.

Pankaj Mishra – poseur, panderer, provocateur. Photo courtesy: CCCB.Org

Now they are caught between a rock and a hard place; they cannot find anything good in the government and cannot be reflexive in their responses to government policies. They are like monotheistic zealots, dividing the social world into the world of good guys, meaning people like them and the world of bad guys, those who are not like them. In the process, they produce social realities that are opposed to debate, openness, and a little doubt about one’s political faith. In the absence of this inwardness combined with the conviction of their moral superiority, they have become ideologues at best and crusaders at worst. Their world does not welcome contrarian thoughts; they always promote agitation and violence, but never introspection or reflection. Though it is recognized that intellectuals do not form a coherent group, the fact is that dissent has become the default definition of intellectual labor, particularly when a nationalist party is in power. But dissent as the foundation of intellectualism is a weak foundation because it reduces intellectuals to agitators and reactionaries. If dissent is to be the bedrock of intellectualism, the intellectual net is to be cast really wide so as to dilute the class status of intellectuals.

What they should not do:

To save intellectuals from obsolescence, here are a few unsolicited suggestions, that will help them reclaim some of their relevance. The first step in that direction is to stop seeing themselves as entitled rather than a seeker who can rise above narrow ideological objectives and herd mentality. Mercantile media and derivative academia dominate this class; there is no space for organic thinkers speaking Indian languages or using Indian idioms. They are elitist, English-speaking and far from being media of positive change; their new credential is writing columns and appearing on TV. They see ordinary people in a condescending way and genuinely believe that they are stooping to educate people. Now they should seriously consider sparing a thought or two over their need to converse with people rather than mock them for understanding the social world differently.

They should stop being uncritical promoters of Western ideas and practices. Whenever a new idea or movement emerges in the West that is notionally reformist, the Indian intellectual class chooses to replicate the same in India lock stock and barrel without much thought about the suitability of those ideas outside of urban centers. That means, when something like MeToo comes to India, its votaries should find Indian vocabulary to address the problem and expand its scope to accommodate the suffering of millions of rural women. They should stop imagining that Indian intellectual traditions do not have the emancipatory vocabulary or that it is not suitable for contemporary life. India has a distinct tradition of toleration and peaceful co-existence, not just in the realm of thought but also as a viable social practice. That will make them see cosmopolitanism within Indian thought.

They should not peddle nationalism as a vice and an upper-caste North Indian fantasy (as Pankaj Mishra believes) just because nationalism in its extreme form wreaked havoc in Europe. Being a postcolonial nation and having come out of centuries of foreign rule, nationalism is the lifeline of our existence as a distinct political community. When intellectuals decry nationalism and create a false binary with patriotism, most people outside humanities academic circles neither see nor want to see that difference. This leads to another problem that they need to address, that is Indo-phobia. They never speak about Indic/Dharmic thought and only cater to the lower level of consciousness limited to the body (rights/reproduction, etc.) or at the most social organization (democracy/secularism), but not ananda, consciousness, and realization that Indian, dharmic culture promotes as the ideal and supreme pursuit of human beings. They need to reflect and meditate more and agitate less; they should also start being evolutionary and integral rather than being angry and revolutionary.

While promoting minority rights, they should learn to respect the belief systems of the majority. Unfortunately, they find fundamentalism within Hinduism, but rarely elsewhere; confront intolerance in Uttar Pradesh, but never in Kerala. They never asked why there was no reservation for Dalits in Kashmir even as they highlighted atrocities against Dalits everywhere. They need to come clean if they wish to be secular or pander to minority sentiments, promote caste mobilization or fight for a caste-less society. More importantly, they should stop being over-confident; sab janta or all-knowing attitude will not do any good to them and will justify the exclusion of people they do not agree with. That means they should stop treating themselves as a superior class with some inherent moral value that others do not possess. Being reflexive is the key here. That means one must continue pursuing intellectual freedom while simultaneously acknowledging that one never actually has it.

Photo Credits: Hindustan Times

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.