Recollections with Sita Ram Goel: Part 1

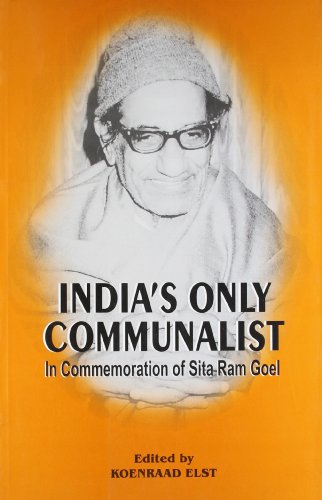

This is the first part of the author’s essay in a volume he has edited: India’s Only Communalist. In Commemoration of Sita Ram Goel, Voice of India, Delhi 2005.

Now that the trail-blazing Hindu publisher and historian Sita Ram Goel left this world in 2003, it would be meritorious for all who knew him to commit to writing their memories of him.

On his earlier years there is extremely little documentation save perhaps for some school records, since all the relatives of his own generation have already passed away. As for his student and early working days, if anyone were to write his biography, his surviving friends would urgently need to be traced and interviewed, before they too leave this world.

Mr. Goel abhorred myth-making. And there is no dearth of myth-making in biographical notes about well-known people, such as the spurious claims about Ramakrishna Paramahansa’s so-called Christian and Muslim mystical experiences concocted posthumously by some of his disciples converted to the agenda of the “equality of all religions”.

He also used to laugh at attempts by modern disciples to know better what great authors intended than can be gleaned from their own explicit utterances, as in “What Marx really said”.

Therefore, concerning Sita Ram Goel’s years as an acknowledged guide of vigilance against Communism and of Hindu awakening, we had better record those of his words not yet available in print lest they get either forgotten or misrepresented, though of course without giving them the same status as the published works which carried his own imprimatur. As a matter of practical history-writing, we ought to compare our memories before time gets a chance to corrode and distort them.

First Meetings

My own acquaintance with the leading light of Hindu awakening goes back to the end of the annus mirabilis 1989, when the dominoes of the Soviet bloc had been falling one after another.

I was living with my wife in a little ground floor apartment in Goyanka Gali near Assi Ghat in Varanasi, but I had come to Delhi for a few days to settle some administrative matters. Wandering around in the booksellers’ area of Daryaganj, I walked into Uppal Publishers’ bookstore and bought Mr. Goel’s book History of Hindu-Christian Encounters, an obvious title of interest for a lapsed Catholic studying Hindu philosophy.

A day or two later, I had finished reading it and found myself back in the same bookshop. Off-hand, I mentioned to Mr. Uppal what a great read I had found the book he had recommended to me. To my surprise, he said that the book’s author could be found in an office just around the corner. He telephoned at once and Mr. Goel’s nephew informed me that the author was expected in the office by 1 p.m. and that I was welcome to come over and meet him.

All afternoon, I was sitting at the feet of the master, taking notes. Mr. Goel was very generous with his knowledge and with his time, though not in the sense of sacrificing his working hours. Ever one of the most active people I have known, he often kept up a lively and witty conversation all while writing letters and signing documents which secretaries presented to him.

A few months later, my wife and I were back in Delhi, and before revisiting Mr. Goel, we dropped by the BJP office and the RSS bookshop Suruchi Prakashan. That way, we got to meet some of the leading Hindu nationalists, such as the helpful Mr. J.P. Mathur and the thoroughly friendly Mr. K.R. Malkani.

The bookshop was a shabby affair, but the fortunate implication was that I could buy the gist of RSS thought for little paper weight to carry and little money to pay. We also tried to meet Mr. Syed Shahabuddin, leader of the anti-temple campaign, but he pretended not to be in his office.

Though the media always identified Hindu activism with the RSS, it took an ordinary listener less than five minutes to notice that Mr. Goel was an entirely different kind of Hindu activist with an entirely different approach from what I had come across in the RSS pamphlets.

Thus, he was rather carefree about one of Hindutva’s biggest scarecrows: the Muslim demographic offensive. Alright, Hindu society was in trouble, but not so deeply as to have no option left except outbreeding the Muslims. When asked about his relations with the RSS, he smiled wearily and said that RSS men were very good at physical locomotion, but that their achievements for Hindu society were limited.

Mr. Goel also took us to the rooftop apartment of his friend Ram Swarup. By then, we started realizing how lucky we were to be introduced to such exceptional company. Listening to their explanations of both the timeless profundities and contemporary weaknesses of Sanatana Dharma, we experienced what Mr. Goel’s son Pradeep would later describe in his Hinduism Today interview: “They won our hearts with their minds.”

[contextly_sidebar id=”rHlKax5UQtxboZy0YjMvXa8ZjktCSz92″]

Having gathered sufficient material for a preliminary write-up on the Ayodhya affair before flying home in April 1990, I promised Mr. Goel he would hear back from me. I sent him my manuscript two months later, and it was rushed into print: Ram Janmabhoomi vs. Babri Masjid, a Case Study in Hindu-Muslim Conflict.

Looking back, I don’t find it very well-written, it was a mere journalistic introduction to the subject and it did not contain much new information for any Indian attentively following the news on the communalism front. Yet it filled a gaping hole in the market, viz. a brief account of the controversy untainted by the Marxist-cum-Islamist agenda which dictated the dominant discourse at the time.

Former Times of India editor Girilal Jain chaired the press meeting presenting my book. It was on this occasion that BJP leader L.K. Advani gave a speech on his Ayodhya policy, waving my book in his hand, and that he made his offer to persuade the VHP to confine their campaign for the liberation of Hindu temple sites to the Ayodhya site, i.e. to drop their claim on the mosque-occupied Krishna Janmabhoomi site in Mathura and Kashi Vishwanath site in Varanasi. That way, my puny first book made the front page of most Indian newspapers.

Fortunately, the opportunity more or less forced Mr. Advani to equally draw attention to a more important new book on the same subject, viz. a collection of scholarly papers and analytical columns on the Ayodhya evidence edited by Mr. Goel: Hindu Temples, What Happened to Them, Vol.1. So, indirectly I could do something in return for Mr. Goel’s favour of publishing my book.

The Hindu Temples book contained his preliminary list of nearly two thousand mosques built on the sites of destroyed temples. Mr. Advani had initially not been too keen on highlighting this research, for it raised the issue of Islamic iconoclasm as an intrinsic feature of Islam, whereas the Sangh Parivar preferred an anecdotal approach confining the debate to just three disputed sites and formulating it in terms of “the national hero Rama” versus “the foreign invader Babar” rather than Hindu versus Islamic.

The list of destroyed temples became a classic illustration of the treatment which the media and academe always gave to Mr. Goel’s work: it was only mentioned in whispers and never openly discussed.

In November 1990, I was back in Delhi and Mr. Goel proposed that I write a sequel to my Ayodhya book. I could stay in the guest room and was provided with a computer. I dropped all the other plans I had made for my sojourn in India and stayed behind that computer screen for nearly three months, except for trips downtown to meet various Hindu leaders and attend press conferences related to the ongoing Ayodhya crisis. Most Europeans return from India with a sun tan, but I had never been as pale as I was after the writing of Ayodhya and After.

Ever since, I have returned to Delhi at least once a year, but never for very long, as my family responsibilities and other social ties in my home society were increasing. But I could always stay in the same guest room and spend lots of time with Mr. Goel.

[contextly_sidebar id=”CF626rpRyj4yFvhqLf3OX4g79yslKzV8″]

In the office, I was also a witness to his interaction with all manner of visitors, a very instructive insight into the inner kitchen of the broader Hindu movement, Sangh and non-Sangh. Though my writings on Islamo-“secularist” policies, largely inspired by Sita Ram Goel, were to cause me some trouble in my professional and social life, I shall ever remain grateful for the privilege of a close association with one of modern India’s greatest men.

His Justice

The overriding recollection I have of Sita Ram Goel is his outstanding generosity. You could always divulge your doubts to him, he was sure to come up with a reassuring though often unexpected answer, one that would really help you on your way forward.

His sense of humour could wash away any blues. He was also generous as well as attentive in the material sense, e.g. unlike the proverbial cold-hearted Bania, he never forgot to take care of the material needs of servants, having food brought to a driver waiting in the car or paying sizable tips to door-keepers.

Yet, Mr. Goel could also be very stern in his judgment. In my case, for example, he could reprimand me when I wasn’t careful with the financial side of things, as when I was allowing myself to get fleeced by a certain type of Indian often found around the supposedly rich Westerner.

Normally an ocean of calm, he also wouldn’t hide his annoyance when I failed to keep up with agreed-upon deadlines, though he never let such irritations come in the way of the realization, even if belated, of Voice of India projects.

On the other hand, if there is any point on which I would criticize him with the benefit of hindsight, it would be for being too lenient with me in one important respect. He was insufficiently strict as an editor, at least in my own case.

When I look at my first Voice of India books now, I find they are insufficiently structured, insufficiently meticulous in identifying sources, sometimes also bringing into the discussion topics that disturbed the book’s proper focus. I suppose he was overly respectful of Western sensibilities, especially those of my own anti-authoritarian generation that had never learned to accept corrections from older people who know better.

He could be stern with people in the sense of making them face their responsibilities instead of accommodating their self-serving excuses. When the Mohajirs were getting butchered by fellow Muslims in Karachi, he pointed out that they were the creators of Pakistan, a state based on communal hate. So, if they became the targets of communal violence in the country of their own making, they could hardly deny they had it coming.

Now, to say this of a Muslim group and of Pakistan is not all that original in Hindu circles. But Goelji took the logical next step. When the Kashmiri Pandits were expelled from Kashmir by the local Muslims and a handful of Pandits visited his office seeking financial help, he did give some money to a refugee organization of theirs, but not without showering them with a very stern sermon. He recounted to their faces the less than glorious record of the Kashmiri Pandit community in the establishment of an anti-Hindu secularism as India’s state religion. Leaders of the Kashmiri refugee self-organizations turned out to have been staunch Communists who only remembered their Hindu identity as soon as they needed to solicit the solidarity of the wider Hindu society.

A few times, Goel’s stern judgment even became a factor in some bad blood developing between him and his mentor: “Ram Swarup sees through ideas like no one else, but he doesn’t see through people. He always manages to join hands with the wrong people.”

During his anti-Communist activism, Ram Swarup’s analysis stood out by its profundity and its spiritual dimension, yet he was cordially in touch with Westerners whose anti-Communism was either of the superficial or of the conspiratorial kind, lacking in serious analysis as well as in spiritual depth.

Goel, by contrast, tended to keep aloof or to maintain a palpably sceptical attitude even when cooperating with people if he considered them as not meeting his standards. He wasn’t a diplomat, and his rule of thumb was: talk straight to scoundrels, avoid contact with fools.

Continued in the next part